Child soldiers still being recruited in South Sudan

- Published

Tom Burridge meets some of the child soldiers of South Sudan

It was a normal school day in May when Stephen and the 80 or so pupils were packed into classroom number 8 in South Sudan.

But as the children listened to the words of their teacher, soldiers from the rebel forces surrounded the school's pale-blue, concrete classrooms.

Stephen describes being frozen with fear as the rebel fighters took him and more than 100 of his classmates.

They were given no choice. They were now the latest young recruits, in South Sudan's bloody civil war.

The United Nations says the recruitment of children in South Sudan's on-going civil war is "rampant". It estimates that there are 11,000 children serving in both the rebel, and government armies.

We met Stephen, and three other boys with similar stories, who are all aged between 12 and 17.

One boy recalled how they "were forced to train, and if we didn't want to do it, we were beaten heavily".

"When we were moving and boys got sick and died they would just be left where they fell," said one of the boys, aged 14.

'Defend your tribe'

One boy asked the soldiers why he had to join their army.

"To defend your tribe," came the reply.

Many children living in camps are vulnerable to being recruited as child soldiers by both sides

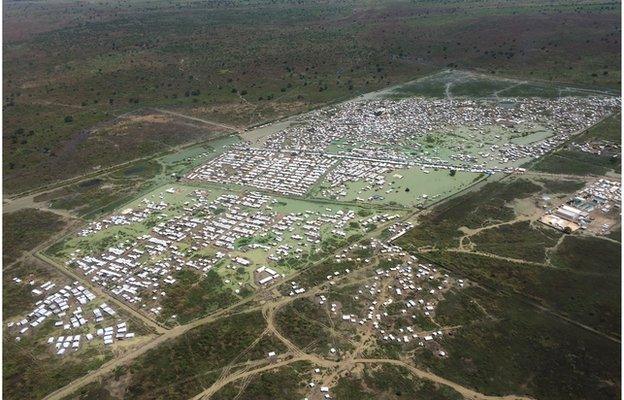

There are around 47,000 people living in the tented camp of Bentiu, which is run by the United Nations

When they were sent to fetch water and fire wood, the boys escaped, walking for days.

They hid at night by tying themselves to the branches of trees to sleep, for fear of being found.

Eventually they reached a UN camp at Bentiu, in northern South Sudan where they are trapped.

If the boys leave the camp and travel the short distance into the nearby town they risk being spotted by soldiers and punished as deserters, in an increasingly brutal war.

Vulnerable

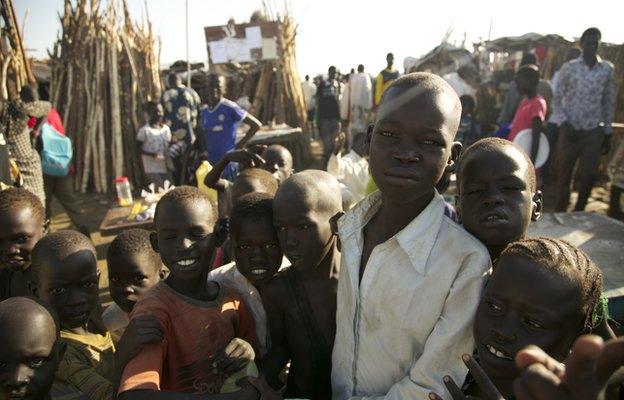

When you walk along the long corridor-like-market at the edge of Bentiu camp where the boys live, group after group of wide-eyed, young, smiling children will crowd around the lens of your camera.

But this is a harsh world for any child to grow-up in.

Every day they wade, some in their AC Milan or Arsenal football shirts, through the muddy, faeces-infested floodwaters that have turned much of their camp into a swamp where 47,000 people live in endless rows of white tarpaulin tents.

Beyond the relative security of the camp's gates, the only schools in the nearby town are abandoned, or occupied by soldiers, because of the on going fighting between Government and rebel forces.

Some child soldiers (not pictured) are among the thousands of refugees at Bentiu camp in South Sudan

The UN estimates there are more than 3,000 child soldiers (none pictured) are on the South Sudan army

In a climate where children have little or nothing to do, they are "vulnerable" to being recruited by either side in the war, says Ainga Razafy, from the United Nations Children's agency, Unicef.

It is easy to spot children carrying guns on the dusty, pot-hole-infested road that runs through the ramshackle town, a short distance from the camp.

"They are obviously associated with the armed conflict," says Ainga Razafy.

According to Unicef around 70% of an estimated 11,000 child soldiers are serving with rebel groups, including the notorious White Army, known for sending thousands of children into battle.

The rebels are fighting the fledgling government of South Sudan, which was itself born out of a rebel movement that spent decades fighting Sudan, and finally won independence in 2011.

But after years of trying to release some of an estimated 20,000 former child soldiers called "Lost Boys" from the army, the current government's ranks are again swelling with minors.

Within days of abducting Stephen, this soft-spoken, fidgety and wide-eyed little boy was on the frontlines of South Sudan's civil war.

It was not possible to get a comment from a rebel spokesperson for one of the many rebel groups accused of using children to fight, but South Sudan's national army, known as the SPLA, admits it has recruited some boys into its ranks.

Some child soldiers (not pictured) volunteer or are pressured by parents to join armed groups

SPLA spokesman, Colonel Philip Aguer, confirmed that 149 children had been recruited in the Bentiu area.

He said SPLA commanders were working to discharge those children, and insisted the SPLA was no-longer recruiting boys into its ranks.

But the UN says that forced recruitment of children continues to this day, and estimates there are around 3,300 children serving in the SPLA.

Colonel Aguer says that this "is not true" and that some children may have been counted twice.

He believes that when the rebels "make mistakes" the UN and other foreign agencies were sometimes guilty of "generalising the blame".

But with limited access, international aid workers across the country told the BBC that the 11,000 figure was a rough figure thought to be hugely underestimated.

Pressure to join the war

Although the boys we met were forcibly recruited into South Sudan's war, there are other factors that drive children into military ranks.

A 12-year-old boy recently told Unicef child protection specialist Sylvester Ndorbor Morlue that he wanted to join the military simply because he felt "it was the best place" to be.

"Some of them see it as employment… and parents are sometimes pushing (their children into the military)."

Whenever the conflict escalates, the demand for military manpower increases, and children are often targeted in a country where nearly half the population is under 15.

As the rain subsides and the floodwaters fall, the slight improvement in conditions will be welcomed by the hundreds of thousands of people living in South Sudan's camps.

But outside, the dry season allows the movement of troops and military hardware.

And the fear is armies that, despite recent peace talks in neighbouring countries, show little sign of peacemaking on the ground, will enforce their rules of war on the young, and claim more of South Sudan's little lives.

The names of the boys quoted at the beginning of this article have been changed for their protection.