Operation Triton: Europe's Mediterranean border patrol

- Published

New maritime patrols aimed at stemming the flow of African migrants making the dangerous Mediterranean crossing to Europe are taking over from the Italian navy. But with a smaller budget there are concerns the operation could lead to more migrant deaths, writes the BBC's Rob Brown.

"The boat broke into two. I watched a lot of people die right there in front of me," says Ghanaian Elias Orjini, describing his first attempt to reach Europe.

"I was in the water for three hours. I would see five or so dead bodies in the water coming close and would have to push them away," he told the BBC.

His is a familiar story of the journey that hundreds of thousands of migrants make every year in unsafe and overcrowded boats.

According to the UN's refugee agency (UNHCR), 165,000 refugees and migrants have arrived in Europe via the Mediterranean so far this year. That is compared to 60,000 in 2013. Estimates say that 3,000 people have died or are missing at sea this year alone - the actual number could be even more.

Facilitating the crossing is lucrative and the unstable environment in Libya is fertile ground for people smugglers. According to the EU border agency, Frontex, it is estimated that the average value of a boat of migrants to traffickers can be more than $1m (£635,200).

Mr Orjini made several attempted crossings, paying about $1,500 each time. On his first trip, the boat sank with only 150 people out of the 500 on board surviving; the next time the engine failed and the passengers had to use their hands to paddle the vessel back to land.

Limited patrols

Many of the boats head for the tiny Italian island of Lampedusa, located off the coast of North Africa, a popular tourist destination.

Discarded fishing boats used to transport the migrants are piled up near Lampedusa's port

A boat load of migrants is estimated to be worth $1m to traffickers

Adverts there encourage visitors to book a boat trip on the crystal clear waters surrounding the island, but stacked up next to the port are reminders of a very different type of boat trip.

Known as the "Boat Graveyard", this is where the dilapidated fishing boats, most painted light blue, used by the migrants end up.

Many migrants have died trying to reach Lampedusa's shores, but when 300 people drowned off its coast in 2013, Italy was prompted to set up operation Mare Nostrum, which translates as "our sea".

The Italian navy proactively patrolled international waters between Italy and North Africa, rescuing boats deemed to be in trouble - a policy credited with saving hundreds of thousands of lives.

But since the beginning of November, a new multi-national European force, called Operation Triton, has replaced it.

It is much smaller, with only a third of the budget of the Italian operation, using seven boats, two planes and one helicopter with personnel from the Netherlands, Finland and Portugal.

Unlike Mare Nostrum, Frontex has made it clear that Triton will focus on "border control and surveillance".

A Dutch border police officer aboard a patrol vessel taking part in Operation Triton

A plane from Finland will be used to patrol the Mediterranean from the sky

However, Frontex's Izabella Cooper insists that search and rescue is an obligation that Operation Triton takes seriously.

"Whoever is detected by our planes or vessels will be saved," she says.

'Radar signals cut'

But some, like UN migration envoy Peter Sutherland, are concerned that lives will be put at risk because of its limited patrol range.

The Italian mission would perform search and rescues right up to the coast of Libya, but Triton's ships will now only patrol within 30 nautical miles of the Italian coast.

The Italian navy has made it clear that it will still attend to any distress call in any location but it will no longer be pro-actively searching for boats in trouble.

"There has to be a full-scale effort to deal with the problem of thousands of people who are drowning in the Mediterranean," says Mr Sutherland.

Under maritime law, private ships are also required to rescue any boat that is in need of help.

But Vincent Cochetel of the UNHCR questions whether they will take on the responsibility, citing an incident of a distressed vessel in August. The rescue centre in Rome could see that there were 76 other ships nearby.

"The call centre called them all, and within one minute there were only six ships left on the radar screen. All the others switched off their radar signal," he told the BBC.

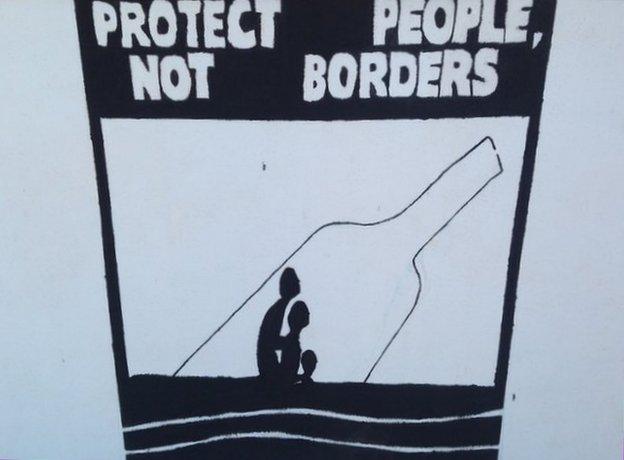

A painting outside the mayor's office in Lampedusa

Meron Estefanos, an Eritrean activist now based in Sweden, regularly receives distress calls from migrants in trouble at sea.

Eritreans make up a large proportion of those trying to make the crossing.

"Many people have told me that when their boat was in distress they would see ships passing by, without stopping, even though they would be screaming and in need of help," she said.

Some in Brussels concede that there are problems with Operation Triton but are keen to point out the fault lies with others.

"The men and women who are involved in Operation Triton are going to do their best, they are going to save lives and are doing a very important job," says UK MEP Claude Moraes.

But ultimately he believes not all member states have done enough to share the economic burden.

No fuel

Operation Triton will not be truly tested until March when the seas become calmer and the migration season begins again.

The Italian navy has said it will continue to respond to all distress calls

Elias Orjini has made a new life for himself in Sicily

As for Elias Orjini, his story has a happy ending: After 12 hours at sea on his third attempt, the boat ran out of fuel but the passengers were eventually rescued and taken to the Italian island of Sicily.

In the Sicilian town of Pozzallo, he met Leandra - a social worker in the migrant camp - who is now his girlfriend.

"When I got to Pozzallo, I was very sad. But the day she came to see me was the first time I smiled and felt some kind of happiness and hope inside me," he says.

He does not see migration as "a problem", more as an individual's need to create better life.

"One way or the other I have to make it because I am a man. I have to take the chance."

Elias Orjini, Peter Sutherland, Vincent Cochetel, Meron Estefanos, Izabella Cooper and Claude Moraes spoke to Newsday on the BBC World Service.