Ebola trials 'best chance' for cure

- Published

Survivors Dr Jules Konundoung and Fanta Camara on their hopes of helping others

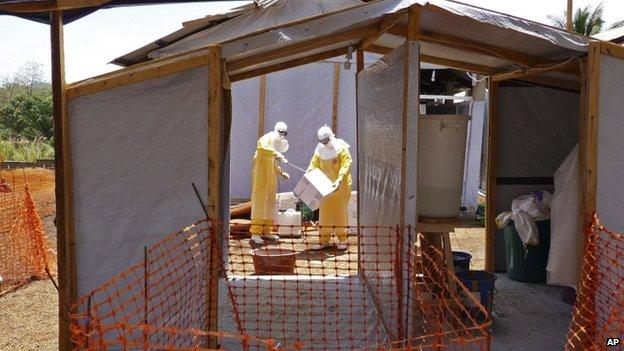

Preparations are under way in Guinea to start unprecedented clinical trials to try to find a cure for Ebola.

The medical charity Medicines Sans Frontieres will host the studies in three of its Ebola treatment centres in West Africa from next month.

One of the trials involves using blood donated by Ebola survivors to treat sick patients.

There are no clinically proven vaccines or treatments for the virus that has killed more than 5,400 people.

Transparency plea

Trying to find a cure in the midst of the worst ever Ebola outbreak is a major challenge.

But scientists say this could be the best chance they have.

At the moment, medics can only treat the symptoms of Ebola, giving people pain relief and keeping patients hydrated in the hope they will be strong enough to fight the virus off themselves.

Guinea - along with Liberia and Sierra Leone - has been the hardest hit by Ebola

The blood of survivors contains antibodies that have successfully destroyed the disease.

The theory is that using their blood to treat infected people will help boost patients' immune systems, giving them a better chance of survival.

But such procedures could prove controversial in communities where some still do not believe the virus exists.

"We would like to be as transparent as possible," said Xavier Trompette, MSF field co-ordinator for Guinea's capital, Conakry.

"We will also communicate in the media to inform the people about what is going on here. Just to avoid people thinking we are making some experimentation on people.

"We will do (the blood donation and transfusions) with the approval of each patient," Mr Trompette added.

Cultural issues

Survivors can face a great deal of stigma from their communities after recovering from the virus.

Conducting trials in countries with decimated health systems will be a major challenge

But a group of them have got together in Conakry to help recovering patients and educate people about Ebola.

Some of them also plan on giving blood in these convalescent blood therapy trials.

Fanta Camara, 25, caught the virus from her cousin back in March when the outbreak was first declared.

"Other patients were dying all around me," she said.

"I was sure it was only a matter of time before my time came, too. I even asked a man at the hospital to tell my mother not to cry too much when I die - because it is the will of God."

But Ms Camara pulled through, and she said she was now ready to help other patients.

"If donating my blood will save others from dying then it will be an honour to do it.

"There's always the question of our culture, but given that this Ebola outbreak is an emergency, I think we can put cultural issues aside."

'No real tools'

Another major challenge will be doing these trials safely in countries with decimated health systems.

Researchers from the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, Belgium, are working alongside the National Blood Transfusion Centre in Conakry to plan how the trials will work.

Donated blood will have to be screened for blood-borne viruses such as HIV and hepatitis. All of this requires more expertise, equipment and medics.

Dr Jules Konundoung became infected with Ebola while caring for a patient. He noticed his symptoms early and made a speedy recovery.

"I think this therapy has a chance of slowing down the outbreak," he said.

"As a medical doctor I know what antibodies are and what they can do to remove strange objects in our systems.

"The only problem is that people would need to be educated on this just to make them feel at ease and confidant about donating their blood."

The World Health Organization (WHO) agreed to the investigation on the use of these kinds of experimental treatments back in September.

"At this point in time… we do not have real tools to treat Ebola. This could be an opportunity to get them," Dr Jean-Marie Dangoutold, WHO country director in Guinea, told the BBC.

He said it was important to get the community on board with the trials, but said that would not be too difficult.

"The population here is mainly Muslim, and Islam doesn't ban blood transfusions - so it's something doable here in Guinea."

Blood treatments have been used in a handful of Ebola cases before and have shown some promise, but this is the first time they will be tested on a larger scale.

It is unclear how effective this one will prove to be, but it offers some possible hope of finally finding a cure.

"I think the blood therapy will give a good result. But we must not be too reliant of this one possible cure," said Ms Camara.

"People must also be educated so they understand how to avoid getting Ebola in the first place.

"Finding a cure and educating people about the virus - must go together to stop this outbreak."