Will Sudan ever find peace in Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile?

- Published

Rebel raids, high levels of crime and deadly inter-ethnic clashes - more than a decade after the Darfur civil war broke out Sudan's western region is as dangerous and as complicated as ever.

The UN says 430,000 people have been displaced so far this year, as Darfur deteriorates after a period of slight improvement.

Yet Darfur is not Sudan's only civil war. The government is also fighting rebels in South Kordofan and Blue Nile.

These areas were relatively calm after the 2005 deal with southern Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) rebels, which ultimately led to South Sudan's 2011 secession.

However fighters in South Kordofan and Blue Nile, known as SPLM-North, were left north of the border. In the lead-up to the split, conflict broke out again in these areas.

A quarter of a million people have now fled into neighbouring South Sudan and Ethiopia to escape fighting and aerial bombardments that many say are targeting civilians.

As the 2014 rainy season ends, many in Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile are expecting the fighting in their areas to increase in intensity.

Divide and rule

But a new approach to the several on-off peace processes that have been taking place for years may offer a way forward.

Negotiations about Darfur were in the Qatari capital, Doha - though many of the main Darfuri rebel groups refused to participate. Khartoum's talks with SPLM-North were in Addis Ababa.

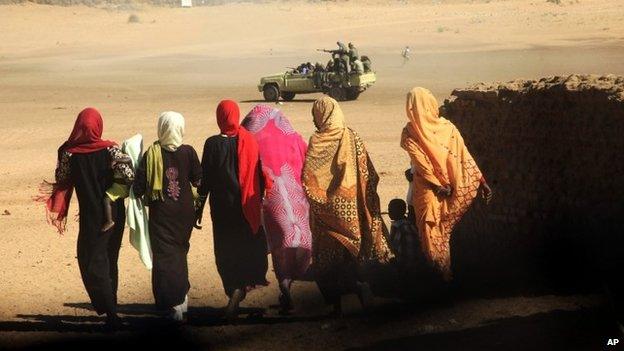

Many people have been displaced in Darfur this year, as fighting continues

But this seemed to the rebels to be a divide-and-rule tactic, employed by Khartoum, and endorsed by the international countries who follow Sudanese events closely.

In 2011, the Darfuris and SPLM-North formed a loose alliance, known as the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF), and since then they have pleaded for a single negotiating platform.

They have almost achieved this aim.

Darfur rebel groups Sudan Liberation Army-Minni Minawi faction (SLA-MM) and the Justice and Equality Movement (Jem) have reopened negotiations with the government.

Significantly, these talks are taking place in Addis Ababa - the same venue as the negotiations between the government and SPLM-North.

Many Sudan analysts have argued that a comprehensive dialogue involving all the problem areas - and including the underlying cause of poor governance in the capital - is the only way forward.

Sudan's failed peace agreements:

2006 Darfur Peace Agreement: Only Minni Minawi's SLA faction signed the deal in Abuja but returned to war in 2010

2011 Doha Document for Peace in Darfur (DDPD): Only signed in Qatar by a coalition of minor rebel movements

2011 July 28 Agreement: Signed by SPLM-North but rejected by the government within days. The African Union has since convened seven rounds of talks to find a resolution

"Sudan's problem is that there has always been a piecemeal approach to settling conflicts that are actually similar," says Suliman Baldo of Sudan Democracy First Group.

"The conflict in Darfur and in Blue Nile and in South Kordofan have now merged because the armed movements have merged.

"The root causes are identical - it's marginalisation, lack of accommodation of diversity and lack of recognition of people from these regions as equal citizens."

Far apart

The African Union's Peace and Security Council now insists that the government's talks with the Darfuris and SPLM-North "should be conducted in a synchronised manner".

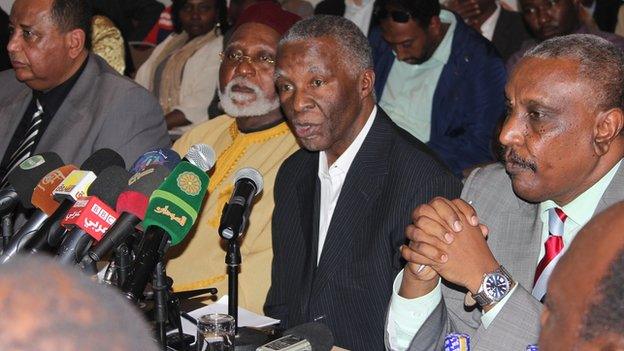

And so both negotiations are in Addis Ababa with former South African President Thabo Mbeki mediating each of them.

The talks are meant to lead to a cessation of hostilities in all the conflict areas, and then to a national dialogue, perhaps linked to a constitutional reform process, and then free and fair elections.

However, this goal seems a long way off.

For the moment, Khartoum is not negotiating with the SRF as a whole.

The opening statements of the Darfur talks on 23 November also showed just how far apart the sides are.

The Sudanese government's Amin Hassan Omar repeatedly referred to the Doha peace process for Darfur, which has been rejected by the Darfur rebels still fighting the government.

Mr Omar said he hoped a ceasefire would "pave the way towards a final resolution of the conflict in Darfur on the basis of the Doha document".

In response, Mr Minawi said President Omar al-Bashir's National Congress Party (NCP) should take "the entire responsibility" for the war.

He also called for the International Criminal Court - which has indicted President Bashir for genocide and war crimes in Darfur, which he denies - to "step up its efforts to bring the criminals who committed crimes before justice".

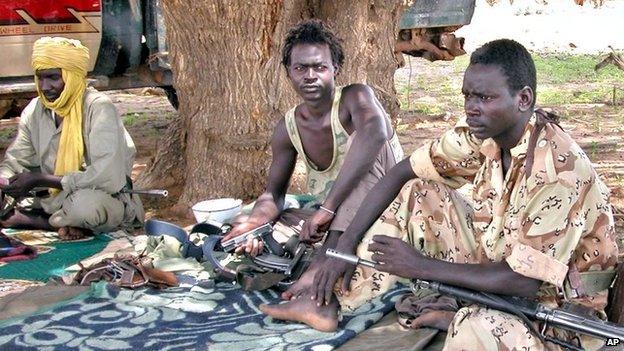

Rebels in Darfur have now formed a loose alliance with those in South Kordofan and Blue Nile

These are not the statements of men who feel peace is near.

It is also clear that there were substantial differences in position at the "Two Areas" talks - as the negotiations between SPLM-North and the government are known.

There have been reports that SPLM-North representatives argued for autonomous rule for South Kordofan and Blue Nile, where most of SPLM-North's members come from.

President Bashir is extremely unlikely to agree to this. In general, Khartoum wants to keep each issue discussed at each negotiation local, while the rebels want unified talks on national governance issues.

This presents quite a challenge for Mr Mbeki.

If progress is made, and a cessation of hostilities is announced - and that is a very big if - a national dialogue involving the NCP, the rebels and unarmed opposition parties would be launched.

Peacekeepers to go?

President Bashir's own national dialogue initiative, which started earlier this year, has made little progress.

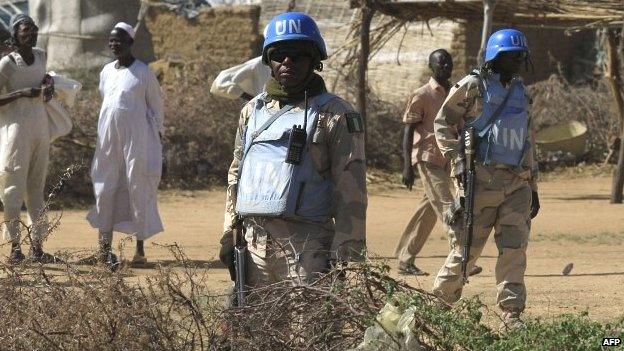

There are nearly 16,000 UN-AU troops on the ground in Darfur

Mr Baldo is sceptical about the motives behind it.

"They are using the national dialogue to bring over opposition parties and give a certain democratic legitimacy to the renewal in power of the National Congress Party."

He believes elections scheduled for next April will not solve Sudan's problems if they take place while wars continue in Darfur, Blue Nile and South Kordofan.

Last month, the Sudanese government asked the joint AU-UN peacekeeping mission (Unamid) to prepare an exit strategy, and shut down its human rights office in Khartoum.

South Africa's former President Thabo Mbeki is chairing both negotiations in Addis Ababa

These signals suggest a dramatic breakthrough is needed if further conflict is to be avoided.

History suggests the odds are against this.

Yet a peace process involving all the rebel groups and a national conversation about how the country is to be governed, is exactly what the rebels have demanded.

Now the question is whether the rebels can be persuaded to stop fighting - and whether the government will make the necessary concessions to allow a genuine national dialogue to take place.

- Published11 August 2014

- Published6 September 2011

- Published3 May 2012

- Published13 September 2023