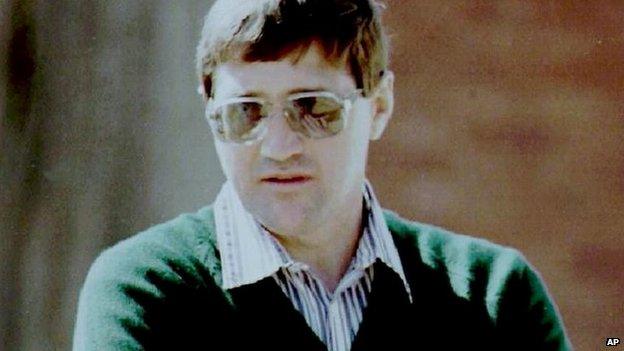

Eugene de Kock: Profile of an apartheid assassin

- Published

Eugene Alexander de Kock, nicknamed "Prime Evil" by the media in South Africa, was part of the apartheid killing machine.

News of his parole after serving 20 years in a South African prison could not be a better birthday gift for the apartheid assassin.

He turned 66 the day before the justice minister said he was being released in the interest of "nation building".

De Kock's primary duty as police colonel was to silence the leaders of the anti-apartheid movement, particularly those from the African National Congress (ANC).

Ironically it is the ANC government that has released him from prison.

'Quiet boy'

Born in South Africa's Western Cape Province, his father, Lawrence de Kock, was a magistrate and a very close personal friend of former apartheid Prime Minister John Vorster.

His brother, Vossie de Kock, described him as a "quiet boy" who "wasn't violent at all".

From an early age De Kock wanted to be an officer in the police.

Eugene de Kock at glance:

Commander of Vlakplaas police unit from 1983

Confessed to hundreds of murders at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Nicknamed "Prime Evil" for the death-squad revelations

Sentenced to 212 years and two life terms in 1996

In 2012, Marcia Khoza publicly forgave him for killing her mother ANC activist Portia Shabangu

Served 20 years before getting parole

Like many young Afrikaner males he first tried the army but he was disqualified because of a stutter.

He became a policeman although his attempt to join the elite Special Task Force unit was turned down because of poor eyesight.

In 1979 he found his feet when co-founded the notorious Koevoet unit.

Its main task was to kill freedom fighters from the South West Africa People's Organisation (Swapo), which was led by Sam Nujoma.

Swapo was fighting for the liberation of present day Namibia.

Koevoet became well known for its high assassination rate.

In 1983, the South African Police transferred De Kock to C10, a counter-insurgency unit based some 10km (six miles) from the capital, Pretoria, on a remote farm known as Vlakplaas.

De Kock rose through the ranks and became the commander of Vlakplaas under a new code name of C1.

This unit became the number one death squad for killing largely black anti-apartheid activists.

Beyond call of duty

He was arrested after South Africa's first democratic elections in 1994 when Nelson Mandela became president.

He appeared before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which was set up by Mr Mandela and chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

At the TRC, De Kock confessed to crimes against humanity.

His revelations shocked South Africans and revealed the length and brutal techniques the apartheid regime was prepared to take to stay in power.

He was granted amnesty for many of the crimes committed in defence of a racial segregation system.

But he was sentenced to 212 years plus two life terms for the murders and crimes he committed which the commission felt went beyond the call of duty.

While serving time in Pretoria's C-Max prison, De Kock conducted a radio interview in which he described the last apartheid leader FW de Klerk as man whose hands were "soaked in blood."

Mr De Klerk, who shared the Noble Peace Prize with Mr Mandela for ending apartheid, denied the allegations.

South African psychologist Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela interviewed De Kock many times while he was in jail.

In her book, A Human Being Died That Night, she argued in favour of a pardon for a man she said had been a servant to a brutal regime.

Whilst in jail, the former police colonel asked for forgiveness from some of his victims.

In a letter he wrote to the family of Bheki Mlangeni, a lawyer he killed with a letter bomb, he said: "There is no greater punishment than to have to live with the consequences of the most terrible deed with no-one to forgive you.

"For me, even my own death can't compare."

- Published9 July 2024