Ebola crisis: Liberia bounces back

- Published

Duncan Bell, MSF: "We don't want to jump for joy but... it is a step in the right direction"

If you thought Liberia was dying, think again.

Yes, the Ebola epidemic was a disaster. Its terrible effects are still present - especially among the poorest in society.

President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf said in her recent State of the Nation address that the disease had "threatened our very existence".

Nearly 4,000 Liberians died from the outbreak.

But now, thanks to Liberians changing their behaviour, and a massive international aid effort, there are only six confirmed cases of Ebola left in the country.

Scouting for trade

If it were not for the prominent posters exhorting people to believe "Ebola Is Real!", and glimpses of mostly empty Ebola treatment centres behind high walls, the casual visitor to the capital, Monrovia, would think everything was normal.

Liberians are now able to socialise in public once again

Life is returning to normal in Monrovia's markets

Aid agencies are burning mattresses and bed frames at treatment centres as their operation ends

Bustling markets and chaotic traffic are back.

Almost every second shop in Monrovia seems to be a building supplier or hardware business.

Their mainly Lebanese or Indian managers have returned, once again sitting in their doorways, scouting for trade.

If bags of cement and scaffolding poles are being bought, it means construction could soon be back up to speed.

But while commerce appears to be normalising, life for many Liberians is still badly affected.

Quite scary

The ruins of the long-abandoned Ducor Palace Hotel offer a panoramic view across the capital.

I visited this place once in the early 1980s when it was the focal point of Liberian high society. Back then, dinner suits and evening gowns were almost compulsory at the Ducor.

Now the place is a mouldering heap of concrete.

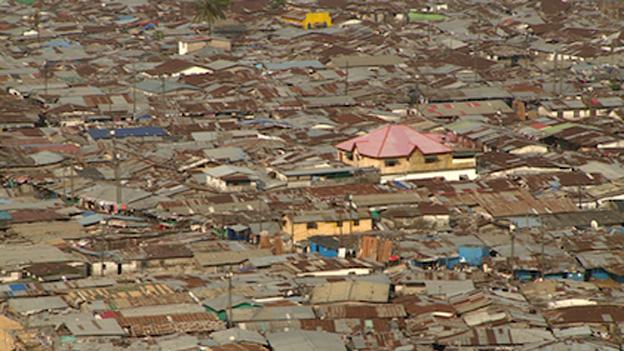

West Point slum was badly affected by Ebola

The climb up the stairs - with all the handrails long-ago looted - was quite scary.

But from the rooftop of the old hotel I was rewarded with a clear view of the vast slum that is the Monrovia city district of West Point - a sea of low shops and homes covered in rusting zinc roofs.

This community of 80,000 souls has only one government school, the Nathaniel Massaquoi Elementary and Junior High.

Right up to the end of last week it had been planned that all schools would re-open on Monday 2 February, after nearly nine months of enforced closure.

Schools, like hospitals, were places where infection spread so the government closed them all down.

Liberia may be returning to normal, but many schools are yet to reopen

Ebola workers are now able to hang up their gloves on a permanent basis

The principal at the Nathaniel Massaquoi school, Momoh Mason, had been hoping that the government would provide him with the resources to reopen to pupils.

But the Nathaniel Massaquoi is an especially sad place.

It was used as an Ebola holding centre at the height of the epidemic.

Local residents reacted violently to the transformation of their school into, as they saw it, a highly infectious dumping ground for the dying.

Huge investments

They attacked it, looting the generator and destroying furniture.

Mr Mason spoke of a lack of resources - books, desks and a lick of paint.

But a major reason why the school lies abandoned is the stigma it now suffers because of Ebola.

"There is fear," he said, "this place is somehow still associated with Ebola and some people are not yet sure about it, especially as the authorities haven't helped me clean the place up".

The focus now is on finding a vaccine for Ebola

Liberians have good reason to celebrate their triumph in seeing off the worst of Ebola

The reopening of all other schools, including those unaffected by Ebola, has also been delayed by at least two weeks.

The authorities said some did not yet have buckets of chlorinated water for hand-washing and thermometers for checking against cases of fever.

Before Ebola hit, Liberia was one of the poorest countries in the world. It still is.

But it is important to remember that in the late 1990s and early 2000s Liberia registered impressive economic growth rates of 8% - 10% - per annum.

I have not been here for several years, and in the interim a number of large international investments, including iron ore mines and several large hotels, have come on stream.

Impressively resilient

To borrow the economists' phrase, it is obvious that the benefit from these investments rarely "trickles down" to the poor.

Dr Stephen Kennedy is spearhading a vaccine trial at a US-financed hospital in Liberia

There are only a few confirmed cases of Ebola left in the country

But the car-owning middle class is clearly growing. The rush hour traffic jams in Monrovia are horrendous.

Despite Ebola, Liberia is not without hope - it may sound a bit of a cliche, but Liberians really are impressively resilient.

They have to be because they suffered over a decade of blood diamond and tribal wars in the 1990s and 2000s.

Successive governments and waves of aid workers here have often disappointed them.

For me, one man I met symbolised the "can do" Liberian attitude.

Slight in stature and naturally modest, Dr Stephen Kennedy is the top Liberian involved in a historic US-financed Ebola vaccine trial.

The vaccine trial Dr Kennedy is spearheading has the potential, at least, to stop the nightmare suffered by Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea from ever re-occurring anywhere in the world.

Dr Kennedy's intellectual capacity is obvious. But the way he describes his role in the first ever trial is also very human and intensely emotional

"I feel so excited," he told me. "This is something that I have dreamed of - to help my country make a major contribution to international public health."

Ebola virus disease (EVD)

Symptoms include high fever, bleeding and central nervous system damage

Spread by body fluids, such as blood and saliva

Fatality rate can reach 90% - but current outbreak has mortality rate of between 54% and 62%

Incubation period is two to 21 days

No proven vaccine or cure

Supportive care such as rehydrating patients who have diarrhoea and vomiting can help recovery

Fruit bats, a delicacy for some West Africans, are considered to be virus's natural host