Why is organ donation taboo for many Africans?

- Published

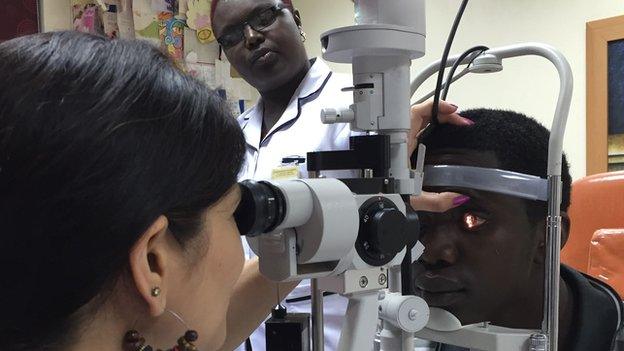

Cyrus Mbugua had been gradually going blind for 6 months until receiving an eye operation

Organ donation - especially in death - is a difficult subject for indigenous Africans.

At the Lions Eye Hospital in Nairobi, the eye bank has never been full since its was set up four years ago.

Dr Jyotee Trivedy, a senior ophthalmologist at the hospital, says the problem lies in the lack of indigenous Kenyan donors.

"One African cornea donor is needed and once we get one African donor I think the rest will be inspired," she says.

Cyrus Mbugua, 17, is one of her patients. He was forced to drop out of school six months ago when his eye sight began to deteriorate.

"It affected my studies so much. I was about the leading student in class, then I started dropping and dropping until the teachers noticed that it was getting worse," he tells me from his hospital bed.

'Seeing heaven'

Mr Mbugua now needs a cornea transplant on both eyes.

"I see almost 14 keratoconic patients per week," says Dr Trivedy, "out of which seven need a cornea transplant".

"As soon as we get a cornea we use it. Like this cornea I got it last week, I'm using it today. I have a patient waiting list. If I don't get the corneas here I get them from the US," says Dr Trivedy.

But corneas from the US cost around $2,000 (£1,233) each, too much for the vast majority of her patients.

Harvested corneas are stored in sterile containers and refrigerated until they are needed

Ideally, a cornea should be removed from a donor less than six hours after they have died. The procedure takes about 25 minutes and does not require the removal of the whole eye.

And yet Dr Trivedy has not had a single indigenous African cornea donor. She has campaigned through the media and appealed directly to religious leaders, but is failing to break the taboo.

"We'd like them to pledge their corneas but because of their religious beliefs, they say they have to see heaven. Still, we've tried to talk to them to donate their corneas so they can help someone see this world."

Grieving relatives

Mr Ngure wa Mwachofi, an expert in social behaviour and communication, says religious and cultural beliefs are to blame for the negative attitude towards organ donation.

"Culture is what people have been conditioned to do from the time they were born and if they are told that certain things are not okay then they believe so," he tells me.

"Belief marks the end of reasoning. No questions are asked. To change that is to provide people with a new argument.

"They need to see that somebody's life can be extended because a good Samaritan had written in their driving licence that in the event of an accident somebody can harvest whatever parts are useful."

Cornea extraction needs to be done soon after a donor's death to ensure that it it as its healthiest

Some Africans have pledged their organs, but that isn't always enough. In one case, a team sent to extract corneas from a donor was turned away by the family.

It is not the kind of fight one would want to get into with grieving relatives, and there is legal framework to prevent the family standing in the way.

Legal delays

Kenya's main referral centre - the Kenyatta National Hospital - has just completed construction of a new liver transplant facility, but it may not be operational for some time because of the lack of organ donation law.

There are laws covering living donors who wish to give an organ to a relative, but none covering those who wish for their organs to be harvested after they die.

Dr Kennedy Ondede, the consultant physician designated to oversee Kenyatta National Hospital's new liver facility, says he is frustrated with an apparent lack of interest in passing new laws.

"A bill has been forwarded to parliament for debate and so we'll have to wait," he says.

The Lions Eye Hospital person various other eye surgeries apart from cornea transplants

Cyrus Mbugua was diagnosed with Keratoconus, a degenerative eye disorder where the cornea thins

Back at the Lions Eye Hospital, Mr Mbugua is recuperating.

A day after undergoing surgery on his left eye, he attempts to read letters projected on a screen about five metres away.

"Cyrus is doing very well," says Dr Trivedy.

"The graft is very clear. He can open the eye in spite of having those 16 stitches ... In another two or three days he should be able to read quite well."

It's good news for a boy who, just a few days before, could not read writing on a blackboard one metre away.

"I'm excited," he says. "I will be going back to school soon."

- Published23 January 2015

- Published15 July 2014

- Published17 March 2014

- Published4 July 2023