Ebola survivor 'hiding' from community

- Published

Andrew Harding looks at the long-lasting damage done to families by Ebola

Siannie Beyan stood on the stage with the other Ebola survivors in Monrovia's City Hall, singing a short, joyful hymn, and trying to hold onto a smile.

As the crisis fades here in Liberia - no new confirmed infections for 10 days and counting - there is a tangible sense of relief.

A tiny country is beginning to shrug off months of isolation and economic paralysis.

Some are even trying out words like "opportunity" as they stand back to survey the impact of the crisis on what had previously been a fast-growing economy.

"It's a rude awakening," the deputy Finance Minister James Kollie told me. "Ebola is not singularly responsible, but it highlighted weaknesses and vulnerabilities in the economy.

"Everything brings with it an opportunity," he said.

Siannie (far right) with her neighbours. She has had to move several times in the last few months

But for 28-year-old Siannie - a mother of three - the future is, at best, uncertain.

"Ebola changed everything. Everything gone bad with me," she said after the city hall event.

She went on to explain the impact of the virus on her own life.

Feeling alone

Last year Siannie, who has never been to school, had been working as an informal trader in Monrovia, selling snacks and toothpaste from a wheelbarrow. She earned about $160 (£100) per month.

Together with her husband's income it was enough to feed the couple and their three children, 11-year-old Joseph, from a previous relationship, seven-year-old Josephine and two-year-old Comfort.

They could also afford to rent a small room and send the older children to school.

Then on 27 August Siannie was admitted to the ELWA 3 Ebola Treatment Unit in town, run by Medecins Sans Frontieres.

"I couldn't walk. I couldn't talk. I was dead and done," she said.

Joseph and Josephine have also seen their lives change dramatically since their mother contracted Ebola

Schools have reopened, but Siannie's children have not returned to education

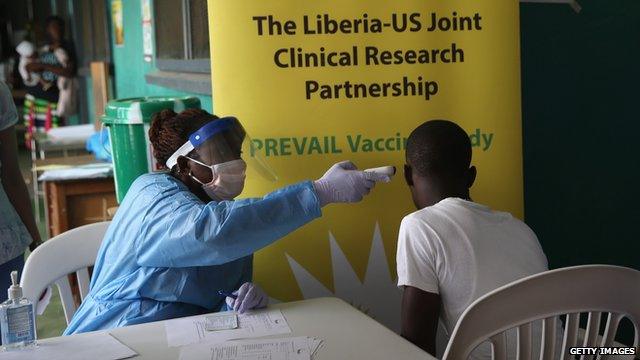

Trials of two experimental vaccines against Ebola have taken place in Liberia

But a month later, she was cured, and headed back to her family only to discover that her husband wanted nothing to do with her, or the children.

"He say he don't want me because I got Ebola. He don't want 'Ebola woman'. I just alone," said Siannie.

"No partner to help me. No family member. No friends. So it very worry me. It worry me how I will manage to bring the children up, to pay their school fees, to pay my rent."

Since December, Siannie has been working at the ELWA 3 centre, helping to counsel other patients.

"They say they coming to die, so we can tell them: 'You will not die, if I can live, then you can live.' I saved many lives here," said Siannie.

She's been earning $400 dollars a month. But the centre no longer has any patients and come next month, Siannie will be out of a job.

In hiding

One evening I went back to the small, dark room she's renting in Paynesville, outside Monrovia.

It's the third place she and her children have moved to since September. Four women sat in the courtyard preparing an evening meal, surrounded by young children.

"I move when people know I got Ebola and was sick. They tell me they don't want me in their house. I keep hiding myself," said Siannie quietly.

"I say [to the children]: 'Don't tell anybody that your mum got Ebola. When you tell them then we'll move'. So the children don't tell anybody up to now. I don't want to move again because I don't have the money," she explained.

She has lost her rental deposit twice.

We heard the sound of singing come from behind the house, and found a local evangelical Christian group finishing their weekly "healing prayer" session under some trees.

"We pray for Ebola to leave this country, but not that they bring Ebola patients to here. No. They [must not] bring them here," said one woman in the crowd.

"We don't accept Ebola patients because we're afraid; we don't even want to see them."

Siannie's youngest daughter, Comfort, is too young to understand what is going on.

But Joseph and Josephine are feeling the stress keenly, as they try to cope with the loss of their respective fathers in an atmosphere of secrecy.

Joseph's estranged father, Abu, died from Ebola in December.

Josephine has not spoken to her father, John, since he turned his back on the family in September.

Many schools in Liberia have now reopened. But neither child has been able to return, partly because they've been forced to keep moving homes and partly because of a lack of funds.

"I want to be an engineer. But my mum got no money," said Joseph, nodding his head with vigour and in sorrow, when I asked him if he missed school.