DR Congo seeks Virunga park boundary change

- Published

Maud Jullien reports: "There's concern that if oil exploration were to start there, their habitat would be in danger"

The Democratic Republic of Congo says it wants to redraw the boundaries of Virunga National Park, a World Heritage site, to allow for oil exploration.

Prime Minister Matata Ponyo told the BBC that there were ongoing discussions about it with Unesco.

British firm Soco is the only company to have explored the park, which is home to endangered mountain gorillas.

It says it would have no further involvement in the block after giving seismic results to the government.

However, campaign group Global Witness said the company could still sell its exploration rights in the World Heritage Site to another company.

The 7,800 sq km (3,000 sq miles) Virunga park is one of the most ecologically diverse places on Earth, but it has suffered from the years of lawlessness and conflict between armed groups based in eastern DR Congo.

Unesco says it has not been made formally aware of a request from the Congolese government to change the park's boundaries.

'Soldiers assaulted oil opponents'

"The necessity is to find a middle ground to see how to preserve nature but also to gain profit from resources so that the communities living there can see their living conditions get better," Mr Ponyo told the BBC.

He said Soco had brought the issue of the boundary to the government's attention, but the company was not involved in the Unesco talks.

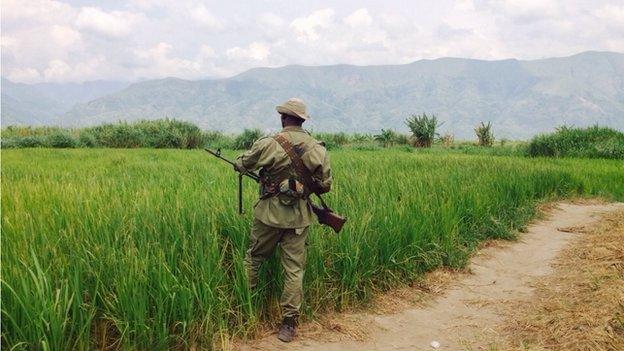

Soldiers are needed to help protect against the area's rebels

Since Soco acquired an exploration permit on Lake Edward, at the heart of Virunga Park, in 2010, it has faced criticism from both conservationists and human rights organisations.

Soldiers have told the BBC that a sub-contractor of Soco had made payments to troops who were part of a unit assigned to the company which has been accused of assaulting opponents of oil exploration in the area.

Soco says it has never paid Congolese troops, directly or indirectly, and condemns violence.

In April 2014, the World-Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) said it was "irresponsible for Soco to disregard the national and international laws protecting the World Heritage Site".

When we arrived in the small village of Nyakakoma, where Soco set up base in 2011, dozens of boats were lined up on the shore, while several hundred fishermen untangled their nets, getting ready to go fishing.

The fishermen are worried about potential oil spills in the area

It is estimated that 30,000 people depend on the lake to survive.

While they haven't always been on the conservationists' side - fishing is restricted and many fishermen would be happy to see the park declassified - many of them share their concerns about possible oil leaks.

The former head of the fishermen's union, who did not want to be named, asked Soco and the government to disclose more information about the oil deal in 2013. He says that several days after he asked, he was detained.

"I was arrested by soldiers, their boss was Major Feruzi - he is in charge of securing Soco's activities.

"They told me: 'You are against oil, we must hurt you.' It was very dangerous."

He said the same major told him several months later that if he did not change his position he would "lose his life." This prompted him to flee Nyakakoma along with his family.

The BBC was unable to contact Maj Feruzi for comment.

Soco carried out tests between April and June 2014 on Lake Edward to determine how much oil it holds.

During that time, fishing was restricted.

One fisherman, who was too scared to be named, told us he had a violent encounter with soldiers during the testing phase.

"I protested," he said, "and then the white man used his walkie-talkie to call a speedboat full of soldiers. They took me and they beat me up, they told me I had no right to speak back to the white man, that I had no right to fish there."

Soco said it could not confirm this incident but has admitted to cutting the nets of fishermen who were in the wrong zone.

Park ranger Rodrigue Katembo also says he was assaulted after being arrested for trying to stop Soco from erecting a mast in the park.

He spent 17 days in detention in 2013 and says soldiers kicked him and crushed cigarette butts on his face during his arrest. He bore visible scars when we met him.

Soco says the Congolese government had assigned soldiers to its security because they operated in a zone where rebel groups are active.

The company says that Major Burimbi Feruzi, who has been identified by several local activists as the man who gave orders to silence Soco critics, was a government military liaison officer assigned to them. The company denies ever paying him.

Soco says the soldiers' salaries were paid by the government in the usual way and that the company did not employ them.

During our time in the area, we spoke to soldiers who told us they were paid by a Soco sub-contractor, on top of their usual army salaries.

Many species live in the vast park which rangers battle to protect

They said they were given an allowance at the end of each month by a South African security sub-contractor for their work securing the company's activities.

"A white South African called Pieter Kock would hand the money to our boss, Major Feruzi, who would then hand it to us," one of the soldiers explained.

They said they were paid up to $300 (£200) a month during their time with Soco, far more then their regular salaries of about $80.

The soldiers we spoke to denied assaulting locals or being ordered to do so.

They said their role was to protect Soco staff from potential threats and to sometimes ask locals to get out of the way of the company's boats.

We contacted Pieter Kock's employer, a South African security contractor, which declined to comment on the allegations and referred us back to Soco.

The park contains about 300 mountain gorillas - about a third of the world's total population.

The Congolese government, which declined to comment on the alleged payment of soldiers by the company, is adamant that oil exploitation in the park would earn billions of dollars - far more than its earnings from tourism.

"You, Europeans, you have eaten all your animals," Joseph Pili Pili, a senior official from the Congolese Ministry of Hydrocarbons, told the BBC, "and now you ask us to turn our backs on money the country desperately needs, the people desperately need, to protect animals?"