Do Africa's colonial relics really matter?

- Published

In our series of letters from African journalists, film-maker and columnist Farai Sevenzo considers if colonial heritage should be forgotten.

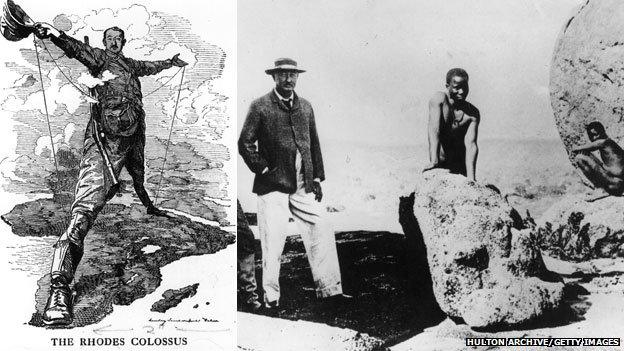

"Rhodes has fallen" - so declared the students at the University of Cape Town when a statue of one of the most influential white men to set foot in Africa was removed with the tacit agreement of the University Council last week.

Since 1934, it had enjoyed pride of place on land bequeathed for the campus in Cecil Rhodes's will.

Rhodes left more than land as part of his legacy - there are scholarships, a prominent diamond mining company, a Rhodes University and more memorial structures than were ever granted to Alexander the Great.

A couple of sizeable African nations were given his name and biographers and filmmakers have for a century and more fed us his life of daring and glory for empire with sycophantic zeal.

Farai Sevenzo:

How more pertinent it would be to erect a statue of the Mozambican man caught by the world's press burning to death as a victim of xenophobic violence in 2008

And if you really feel like bonding with his bones, you can visit the Matobo Hills south of the city of Bulawayo in what used to be called Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, and see a grave hewn from solid granite and read the words: "Here lies the remains of Cecil John Rhodes".

His name is as common in these parts as dust.

South Africa's xenophobic violence is partly caused by resentment over lack of jobs

But the anger directed towards the bronze statue of the dead imperialist is more about the slow pace of transformation in this young democracy, where jobs are scarce for non-whites even after university education, where higher learning is dominated by white academics and where the everyday struggles of the poor are as infinite as Cecil Rhodes's fortune.

Cecil Rhodes, imperialist diamond magnate: 1853-1902

Founded De Beers diamond company

Dreamt of building a railway across Africa without leaving British territory

Zambia was once called Northern Rhodesia

Zimbabwe was once called Southern Rhodesia

Created a scholarship for 83 students a year to go to Oxford University

Travelling around South Africa at the moment it is difficult to escape a perceptible air of uncertainty. The headlines are about power cuts and clean water, xenophobia, rape and the lack of opportunities for the young.

Those Africans who want to bring their skills here are treated with suspicion and the struggle to survive has been picking at the scars of reconciliation that have never truly healed.

'Let's leave him down there'

All over the world there are graveyards full of statues which no longer chime with changed times.

But old Rhodes' legacy is stitched into the fabric of this half of the continent.

The custodians of that legacy have joined the names of "a 19th Century imperialist and a 20th Century liberator" to create the Mandela Rhodes Foundation.

Africa's most fervent "anti-imperialist", Zimbabwe's leader Robert Mugabe took an eraser to many old names around his country. He changed Cecil Square, named after Robert Cecil the British prime minister at the time of Rhodes' expansionism, into Africa Unity Square.

Yet even he has said will not dig up the gold digger.

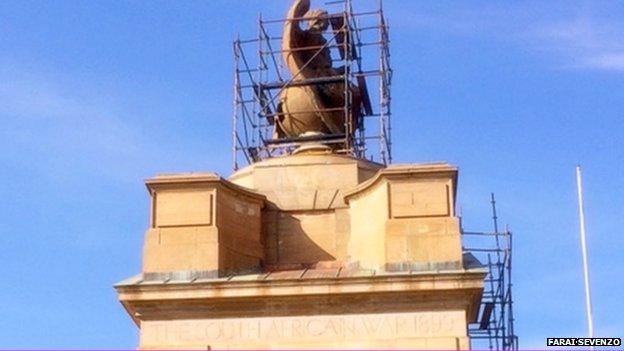

Monuments from colonial times are dotted around South Africa...

Several have been vandalised, including this one of Paul Kruger - revered by many Afrikaners

"We are looking after his corpse, you have his statue. I say to my people let's leave him down, down, down there," President Mugabe said on a state visit to South Africa last week.

Meanwhile, the Cape Town university students' protest has started a spree of statue vandalism - paint has been thrown on Queen Victoria's solid frame, on Afrikaner leader Paul Kruger's statue in Pretoria and even the figure of Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian independence hero, has been painted white for his alleged support of race separation during his two-decade stay in South Africa.

Politicians are now throwing firm words around about "white arrogance" and "no master race", clearly trying hard to make the most of the students' mood.

But do Africans need to be reminded daily of what they once were?

Pastor Xola Skosana told students at the removal of Rhodes's statue: "If we and our children cannot see ourselves in the architectural design around us, then we remain visitors to the only corner of the world God gave us. Europe, we visit, Africa we live in."

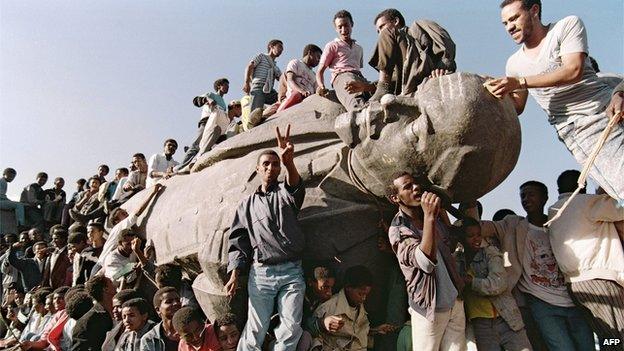

Samora Machel now stands in place of "the pacifier of Mozambique" outside Maputo's City Hall

Ethiopia was never colonised, but after the overthrow of its Marxist ruler Mengistu Haile Mariam a statue of Lenin was toppled

Some countries quietly removed their colonial statues - General Charles Gordon's statute was placed in Sudan's capital, Khartoum, in 1904 but was moved in 1959 to Lightwater in Surrey, to a school that still bears his name.

Samora Machel packed all his Portuguese imperialists into a museum as soon as he took charge in 1975, including the horse-riding figure of Mouzinho de Abuquerque, known in Portugal as "the pacifier of Mozambique", which once stood in front of Maputo's City Hall.

And French colonialist Louis Faidherbe no longer stands outside the Senegalese parliament.

Perhaps this illustrates that it is the setting of these colonial statues that is the problem in South Africa.

Rhodes's bronze was flanked by the majesty of the Cape landscape - it seemed to revere him and condone his imperialism.

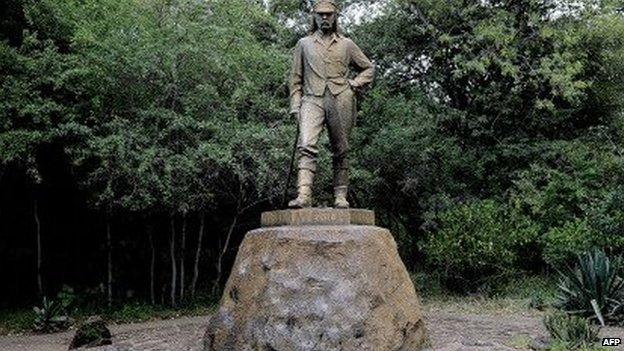

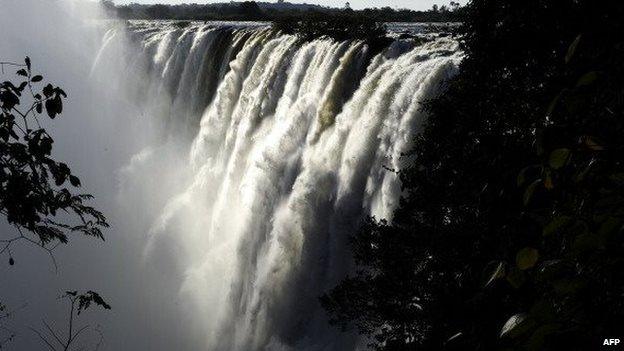

The statue of British explorer and missionary David Livingstone still looks over Victoria Falls...

The majestic site is know locally as Mosi-oa-Tunya, meaning the "Smoke that Thunders"

The symbolism of these statues is heavy with the weight of a history that was at most times brutal to the Africans in whose lands they stand; yet is a complicated relationship.

Should the Victoria Falls still be named after a dead English queen? Should the statue of the man who claimed the falls for her - David Livingstone - still be looking over it in 2015?

The graves and statues of old colonial folk still attract the tourists and everywhere you look there are more pressing problems than the removal of colonial relics.

How more pertinent it would be to erect a statue of Ernesto Alfabeto Nhamuave in a prominent South African square. He was the Mozambican man caught by the world's press burning to death as a victim of xenophobic violence in 2008.

Correction 21 April 2015: This article has been changed to clarify that Cecil Square, now Africa Unity Square, in Zimbabwe was named after Robert Cecil, a 19th Century British prime minster.