From Mali to Sicily: Reporting the migrants' route

- Published

As hundreds of migrants continue to drown making the deadly sea crossing from Libya, BBC correspondents report from some of the stops along the route to Europe's shores.

Alex Duval Smith in Gao, Mali

There is little reason to believe putative migrants from sub-Saharan Africa will be deterred by the reports of mass drownings.

Many departing West African migrants I have spoken to in the past few weeks make it clear that crossing the Sahara, then the Mediterranean, is a life-and-death decision.

It is also, for them, a no-brainer: stay behind and suffer the indignity of living off your elders, with no prospect of being able to marry or support a family?

Or leave and maybe strike it rich like so-and-so, who built a concrete house for his ageing mother and sunk a borehole in the village.

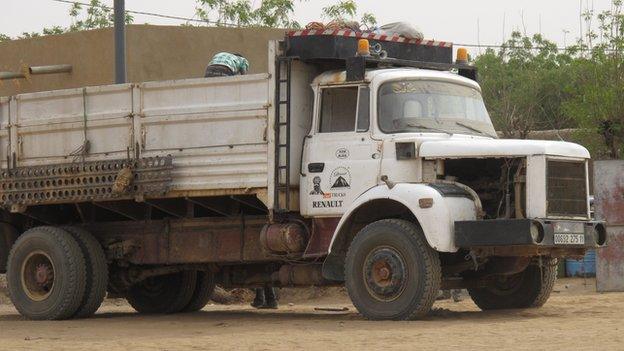

The migration business is the mainstay of Gao's economy

"Their attitude is: Better die for something than live for nothing," said Papa Oumar Ba, a trafficker turned Red Cross worker in Gao, northeastern Mali.

Many others are naive and ill-informed. They have only the traffickers' lies to go on.

"What's the desert?" asked one Gambian I spoke to shortly before he boarded a truck for a potentially deadly five or six day open-top drive across the Sahara.

Papa Oumar Ba said: "In Gao, the traffickers call the Mediterranean 'the river'. It works on those who have never seen the sea."

Others head in trucks to Tamanrasset in Algeria and then either to Morocco or Libya

Firas Kilani in Zintan, Libya

Hundreds of African migrants are still arriving in Zintan, western Libya. It is just another stop on their long journey to Europe.

Dozens of them gather in the main roundabouts, hoping to earn a day's wage, as they need to collect the $1,000 (£670; €930) to pay the smugglers to cross the Mediterranean to Italy.

They are aware of the risks, but simply want to end this chapter in their life and start a new one.

The migrants in Zintan are willing to risk everything to reach Europe

"The only way to get there [Europe] is to cross that water," says John, from Ghana. "I know it's very risky but I'm putting everything in God's hands."

The city of Zintan may be over a hundred kilometres from the sea, but officials here say they are struggling to document all the migrants.

So far they have not received any help.

Zintan's local authorities admit that as Libya remains locked in a crisis between two rival governments, it will be impossible to curb the activities of the migrant-smuggling mafia.

Returning home is not an option for the migrants in Libya

James Reynolds in Catania, Italy

The first survivors to step off the Gregoretti coastguard ship that rescued them on Sunday looked exhausted and in shock. They did not show much emotion and stood quite still on the boat before walking onto the quay.

One migrant was carried off the ship in a wheelchair. A Save the Children spokesperson said it looked like he had a bandaged leg.

One migrant shook hands with the mayor of Catania Enzo Bianco who came on board the Gregoretti with a group of officials. The survivor put his hand to his chest to thank him.

An ambulance also left the scene but we cannot confirm who was on board. There were dozens of Italian officials on the quay - many from the police, port authority, NGOs, the Italian Red Cross.

Surviving migrants disembark from a coastguard ship in Catania

"They are completely shocked, they keep repeating themselves, saying they are the only survivors," said Francesco Rocca, president of the Italian Red Cross who met the migrants.

"Some of them want to speak, some of them want to stay silent. You can imagine they are under a lot of pressure. It's the first time I see such a high level of shock. It's clear from their eyes."

Later we did see some smiles on the faces of the survivors, and there were moments when the migrants and the coast guards appeared to share a joke.

A group of women carrying flowers joined the officials gathered on the dock to welcome the migrants.

Protesters on the quayside carry flowers in support of the migrants

Activists from Catania also staged a protest to denounce the EU's immigration policy. They chanted slogans in Italian: "No more shipwrecks, no more deportations."

One protester, Alessio Grancagnol, said: "We think that the politicians are hypocrites. They have never done anything to solve this problem. Europe could act."

Another protester, Ivana Ioppolo, said: "We are speaking about life, about people who are trying to escape war and poverty. We have to help them."

On the Italian side, there was quite a well-organised media operation to focus the attention on their efforts to deal with the influx of migrants. And there was a wall of cameras to film them.