Burundi: What is behind the coup bid?

- Published

Your 60-second guide to Burundi

An attempt to overthrow Burundi's President Pierre Nkurunziza has ended in failure.

One of the army generals involved in the plan to seize power, while the president was in Tanzania, has admitted defeat.

The crisis follows weeks of protests against the president, mainly in the capital, Bujumbura.

Why has there been a coup attempt?

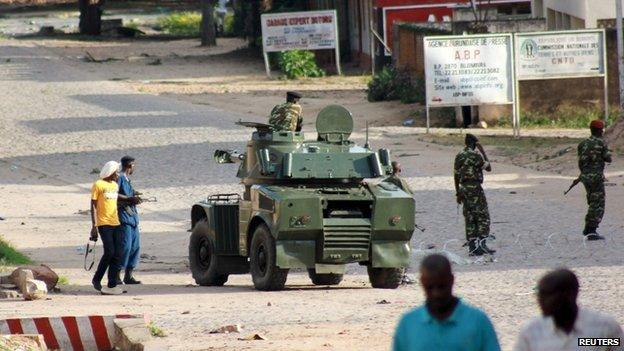

Reports of the coup brought thousands of people out on to the streets of Bujumbura

The trouble began in April when it was announced that President Nkurunziza would run for a third term.

Protesters took to the streets saying the former rebel leader, who has been in power for nearly 10 years, was not entitled to do so.

They are unhappy that the constitutional court ruled that as Mr Nkurunziza was appointed by parliament in 2005 - and not directly elected - he could stand again.

Some army generals agreed that this flew in the face of the peace accord that ended a brutal 12-year civil war - and said they had relieved the president of his duties.

Who is in charge?

Loyalist forces have regained control of Bujumbura after two days of fighting in the city, with the last main battle centred around the offices of the national broadcaster.

Coup bid leader Maj Gen Godefroid Niyombare, a former ally of the president, is still on the run, though three of his colleagues have been arrested.

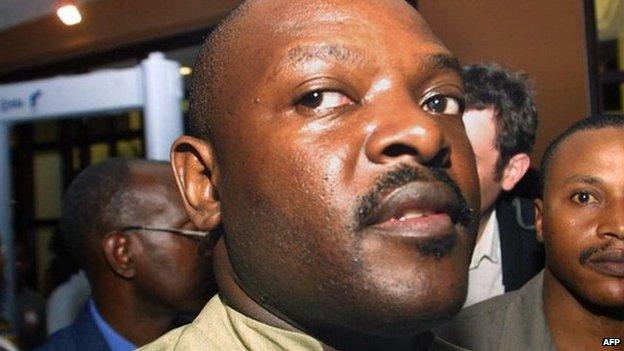

Pierre Nkurunziza, a former rebel leader, has been in power since 2005

Gen Niyombare was dismissed as intelligence chief in February after advising Mr Nkurunziza against seeking a third term.

On Wednesday, he announced on radio that a committee, including five generals, was taking command - and thousands took to the streets of the capital to celebrate.

Could Tutsi-Hutu divisions resurface?

Burundi is a densely populated, landlocked country, like neighbouring Rwanda. It also has a similar ethnic make-up, with a Hutu majority and Tutsi minority, which had long controlled the country.

It has had prolonged periods of conflict, including assassinations, coups and ethnic massacres. Some 300,000 people were killed in the civil war between ethnic Hutu rebels and the Tutsi-dominated army.

More than 500,000 fled their homes during the civil war - some only returned earlier this year

The country has been largely peaceful since 2000, when international mediators brokered a deal to end the conflict.

Under the agreement, the army was split 50-50 between Hutus and Tutsis.

This means that unlike the police, whose officers have been forceful in putting down the anti-third term protests, the army is regarded as a neutral force.

Is the army united?

No. There are internal divisions - with former Hutu rebels regarded as loyal to the ruling party and those in the old Tutsi-dominated army seen sympathetic to the opposition.

However, these historic ethnic tensions do not appear to have been a factor in the coup attempt.

The army is made up of Hutus and Tutsis

The announcement was made by Gen Niyombare, a Hutu like the president with whom he had fought as a rebel.

On the other hand, the Hutu army chief of staff, Gen Prime Niyongabo remained loyal to Mr Nkurunziza.

Have any militia groups been involved?

There are reports that the ruling party's youth wing, Imbonerakure, is turning into a militia group.

Weapons are alleged to have been handed out to them, and they are said to have been behind the attacks on private radio stations seen to be supporting the coup bid.

There are also allegations that some of its members have received military training by Burundian officers over the border in the Democratic Republic of Congo - denied by the ruling CNDD-FDD

Some of the thousands people who have recently fled to neighbouring countries say they were threatened by Imbonerakure's members ahead of elections in June.

What is life like in the country?

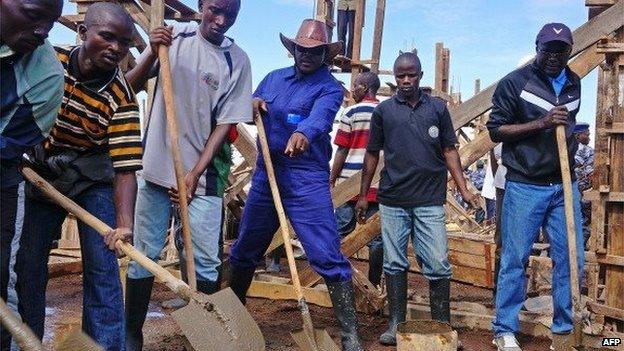

Mr Nkurunziza (C) has spearheaded a reconstruction effort

One of the world's poorest nations, it had begun to reap the dividends of peace and rebuild its shattered economy - though corruption is still a huge issue.

Until the recent unrest, Burundi had proved better at forging national unity following the turbulent 1990s than Rwanda.

The fear now is that the row over the third presidential term could descend into conflict again, either along ethnic lines or along the new divisions in the military.

- Published14 October 2015

- Published31 July 2023