The shadowy centre helping former al-Shabab members quit

- Published

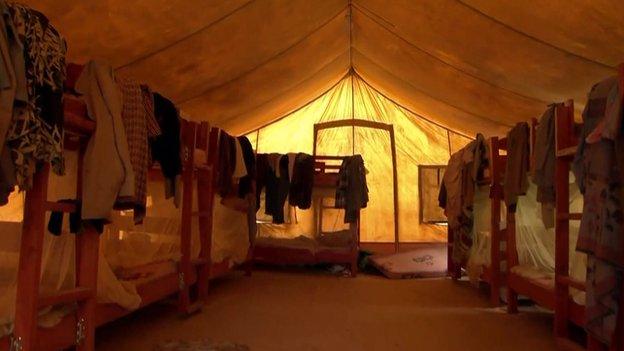

Eighty former militants are housed in the camp

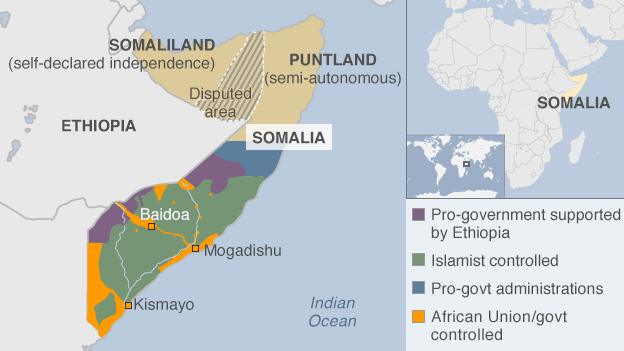

In a small, heavily guarded compound on the bullet-riddled outskirts of Baidoa, a secretive team is working to undermine Somalia's Islamist militant group, al-Shabab, from the inside.

"We can't just solve this militarily," said Aden Mohamed Hussein, ushering me past the soldiers at the gate.

"So far so good... We hope for a domino effect."

Mr Hussein runs a new "disengagement" programme for surrendering al-Shabab members at the camp here in Baidoa, an hour's helicopter ride northwest of the capital Mogadishu, towards the Ethiopian border.

Al-Shabab no longer controls the town or, we're assured, the surrounding countryside. But attacks are still frequent and our time inside the compound is strictly limited.

Such are the alleged sensitivities surrounding what goes on behind the high stone walls, that the international organisation in charge has asked not to be named.

Read Andrew's other reports from Somalia:

The same goes for all the former al-Shabab members, 80 in total, who are currently being housed here.

I can reveal that the German government is funding the programme.

Britain is supporting another, similar camp in Mogadishu, which remains entirely off-limits for journalists.

"These are the lower risk cases. Not the assassins or the explosive experts," said Mr Hussein.

BBC News team goes inside the compound rehabilitating former al-Shabab members

Given the thousands of al-Shabab militants still thought to be active, I asked him if the programme wasn't just a drop in the ocean.

"Absolutely not. If we can accelerate and do more of this kind of work I believe we can overcome [al-Shabab].

"We hope the people here can spread the word, that they have been welcomed, that there's no need to die in the bush," he said.

The first thing you notice inside the compound is the noise.

A loud generator is powering a welding kit, as two men hammer at a steel girder.

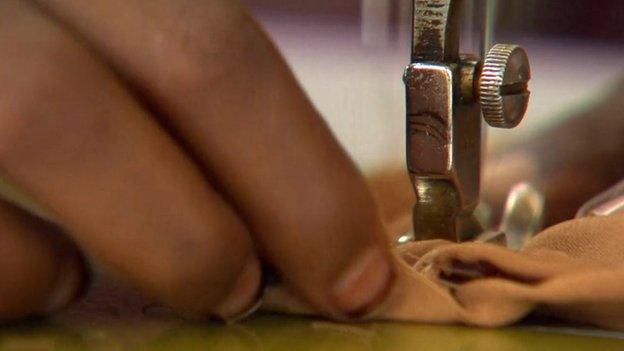

Three men are shovelling gravel into a barrow as more prepare to make breezeblocks. And in the far corner, five women are working at a row of pedal-powered sewing machines while beside them four men are busy dismantling a car engine.

"No-one forced me to join al-Shabab. They were telling everyone to come and fight for Islam. So I joined up," said Mohammed, 30, a short, earnest man who used to be a shopkeeper in Buur Hakaba, in the Bay region of Somalia.

Five years ago, Mohammed became a tax collector for al-Shabab, who controlled the town.

"I was trusted, and I knew maths," he explained.

"We collected money from trucks bringing goods from Mogadishu. We took $6m (£3.8 million) a month," he said with a hint of pride.

The heavily-guarded camp is found on the outskirts of Baidoa

"Even after the government retook the area, we were still collecting $2.4m a month for al-Shabab," he said.

This observation - even if it is unconfirmed, and quite possibly exaggerated - speaks volumes about the failures of Somalia's new authorities to fill the vacuum left behind as territory is captured from the militants.

"It was the atrocities that made me use my head, and get out. I saw that these people were terrorists.

"Al-Shabab terrorised their own community - forcing people to give more money than they can afford. It was all about money - not religion. Then I heard the government was granting amnesties to people who leave, so I took advantage of that," Mohammed said.

"Al-Shabab can be destroyed. But I'm not seeing any signs of that yet. They're still collecting money in two areas I know of right now.

"Still, this [camp] is one of the solutions. We're being reintegrated here and given money to start businesses. No-one wants to stay in the bush and earn nothing. It's hot and bad there," he said.

Mr Hussein, the project coordinator, said some of the newer arrivals at the camp had openly admitted they had surrendered more out of curiosity than conviction.

Mohammed told us he worked as a tax collector for al-Shabab

"Some of them will even tell you 'we are ambassadors - we've been sent [by others in al-Shabab] and if you treat us good then everyone will come'.

"Right now, even the ones who are in the centre are calling their old colleagues to say 'hey - we have protection here,' because others fear that when they come they will be killed. And I believe many, many, of them will come. So we are going to demand a larger space here," he said.

Hanat, 25, says he joined al-Shabab in 2006. He was unemployed and bored, but quickly discovered that his new bosses would not let him leave.

"In 2010 they took us to Mogadishu. We didn't have enough ammunition, not enough training - we were fighting a hide-and-seek war," he said, describing the intense urban warfare that raged in the capital against African Union and Somali government forces.

But then Hanat made a phone call that changed everything.

"My brother had been abroad, training in Uganda with the Somali national army.

Residents are taught new skills to aid their rehabilitation

"When I joined al-Shabab I was told to switch off my phone, so I had no communication with my family, but later, in Mogadishu, I switched it back on and tried calling my brother.

"He told me he was on the front line. Right there. Opposite me. I decided that if I fired another shot it would be my brother who would die. And if he shoots - he'll kill me.

"We spoke just once on the phone. It was a very long conversation. He told me the government had more ammunition and better training, and I didn't want to die.

"So I changed my mind about what I was doing, escaped from Mogadishu, and when the government took control of Baidoa, I came here.

"I called a government official and told him I'd been with al-Shabab but had decided to leave. Then they welcomed me here," he said.

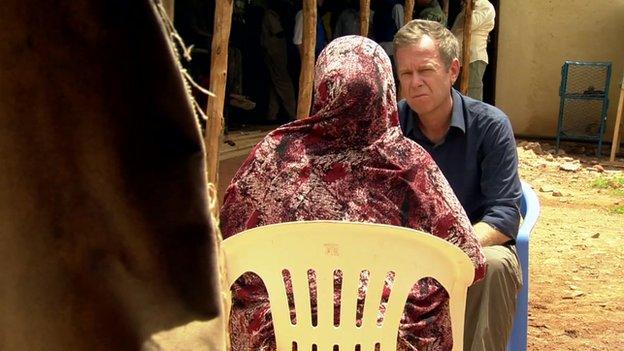

Across the courtyard, beside a tent packed with bunk beds, one of the handful of women in the camp came over to talk to me.

The men learn how to assemble car engines

Unlike most of the men, 20-year-old Fatoumah had not joined al-Shabab willingly.

"I remember the day they kidnapped me. I was coming from school, and they forced me into their car.

"They tortured me, and starved me. Then they raped me. Eventually I had to submit - that was the only way I could save myself," she said.

"The torture lasted for eight months. They did bad things to me. Then they made me marry an Emir - a commander - of the group. One of my three children is his. The other two are from a different fighter.

"My first husband died. Then I was made to marry another. They were merciless. I was with al-Shabab for three years. There were other women with me - some foreign.

"I served the fighters food and water. When they went to war I had to provide first aid. We went into battle with them and even fought along side them.

"One day we were in a convoy going to fight and there was an ambush by Amisom (African Union forces). When I got wounded in my side they abandoned me.

Fatoumah said she was kidnapped, tortured, and raped by al-Shabab members

"I went to hide in the bush. Later some people found me and gave me traditional medicine to heal my wound, then they took me by camel to a safer area," she said.

Eventually Fatoumah was brought to the camp in Baidoa - partly for her own protection.

"I was part of them - and they didn't want me to leave. Whoever tries to leave must be killed.

"So they sent several people to kill me, including someone with a suicide vest - he blew himself up when he met me. That's why I have this scar on my head," she said, pointing to a line on her forehead.

The Baidoa camp serves many roles.

It offers former combatants a chance to retrain, and also to confront what they've done - a new programme called "Tree of Peace (or more literally, Acacia of Peace) is developing a Somali-led process of truth and reconciliation for communities ripped apart by the conflict.

But for many of those living here, the camp is above all a sanctuary - a guarded compound where people like Fatumah are relatively safe from al-Shabab.

Useful, no doubt. But the question looms - how long will people have to stay here before they feel safe to return home?