Eritrea ruled by fear, not law, UN says

- Published

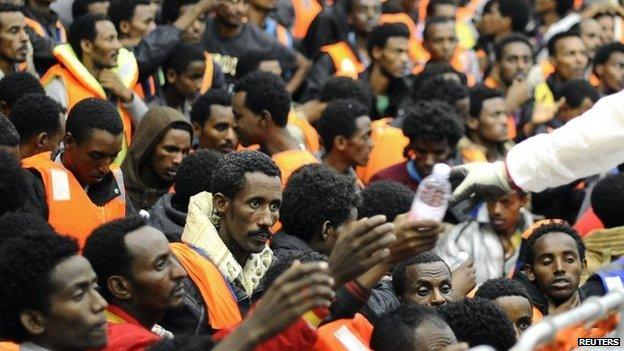

An estimated 5,000 Eritreans flee every month, often attempting to cross the Mediterranean

Eritrea's government may have committed crimes against humanity, including a shoot-to-kill policy on its borders, a UN investigation says.

"It is not law that rules Eritreans - but fear," says the report, external, which details extrajudicial killings, sexual slavery and enforced labour.

The situation has prompted hundreds of thousands of people to flee the country, says the report.

Eritrea declined to take part in the investigation, the UN says.

It has previously denied committing human rights abuses and says those leaving the country are economic migrants.

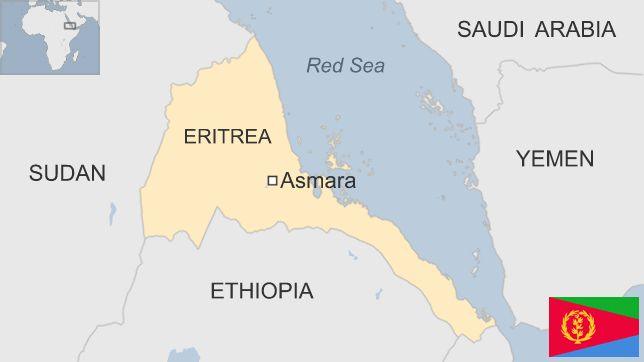

President Isaias Afewerki has governed the East African nation for 22 years, and the country has never held elections since gaining independence from Ethiopia in 1993.

Eritreans account for the second-largest group of migrants crossing the Mediterranean, after Syrians, with an estimated 5,000 fleeing every month.

The policy of military conscription for Eritreans once they reach the age of 18 is thought to be one of the main reasons people flee the country.

Eritrea at a glance:

Gained independence in 1993

6.3m population

Opposition parties outlawed

Conscription can last until the age of 40

UN estimates 5,000 Eritreans leave each month

Heavily dependent on earnings of the diaspora

The UN says many conscripts are made to remain in the army indefinitely, where they receive very little pay, and are subject to forced labour and torture as a form of punishment.

A shoot-to-kill policy on the country's borders, announced by the government in 2004 to prevent Eritreans fleeing the country, cannot be said to have been "officially abolished", the report said.

The UN says Eritreans are forced into indefinite conscription, under terrible conditions

Despite several eyewitness reports and government statements suggesting that the policy was no longer being implemented, witnesses who tried to cross the border this year and in 2014, told the commission that they had been shot at by soldiers.

The year-long investigation by the UN commission of inquiry accuses Eritrea of operating a vast spying and detention network, holding people without trial for years, including children.

Neighbours and family members are often drafted to inform on each other, according to the report.

"When I am in Eritrea, I feel that I cannot even think because I am afraid that people can read my thoughts and I am scared," said one witness interviewed for the report, describing the fear and paranoia created by the state's mass surveillance programme.

The inquiry said that "systematic, widespread and gross human rights violations have been and are being committed in Eritrea under the authority of the Government".

The investigators are to present their findings to the UN Human Rights Council on 23 June.

- Published13 March 2015

- Published15 March 2015

- Published23 February 2015

- Published18 April 2023