Karake arrest strains fragile UK-Rwanda relations

- Published

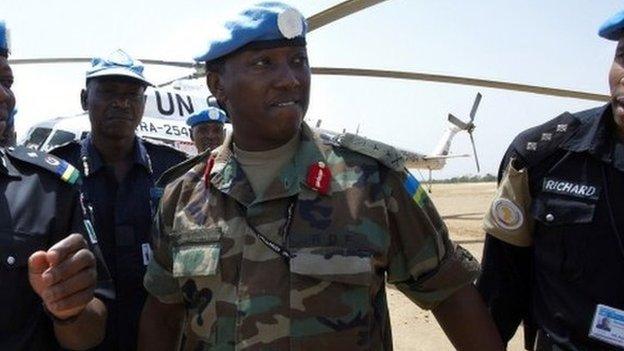

The arrest of General Karenzi Karake in London is bound to strain what is increasingly becoming a fragile relationship between Britain and Rwanda.

Like two best friends, harsh words are exchanged from time to time, but on this occasion it feels like a smart slap whose sting may last for some time.

It is perhaps not surprising that the detention of Rwanda's head of intelligence is being flagged up by London as a European "obligation" rather than a British decision.

There is a strong ambition in Whitehall that the matter simply goes away. After all it was a Spanish high court judge that made the accusation of war crimes, not a British one.

Rwanda has long been considered by Britain as one of its closest allies in the region and "an African success story".

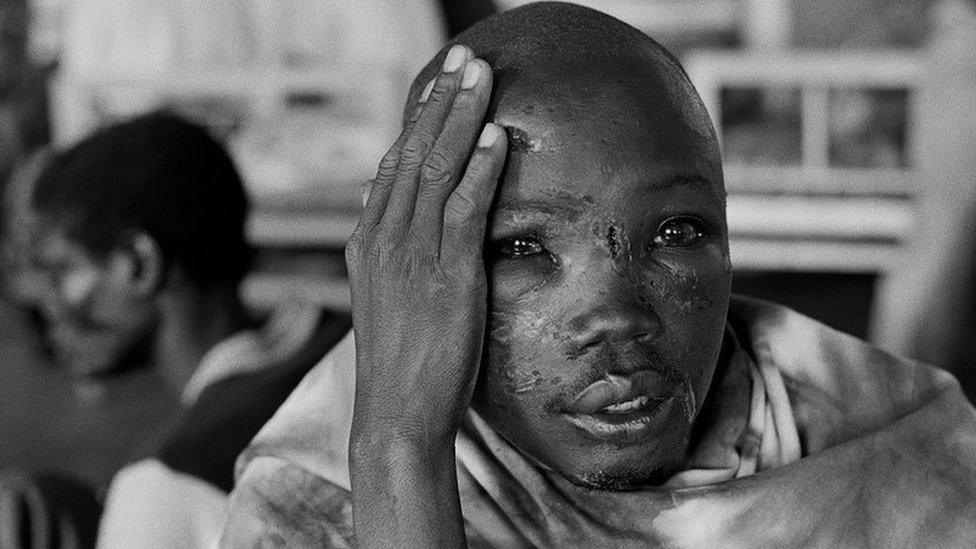

Following the genocide in 1994 in which 800,000 mainly Tutsis perished in unspeakable violence, Britain has pumped millions into development aid and Rwanda has responded with impressive rates of economic growth.

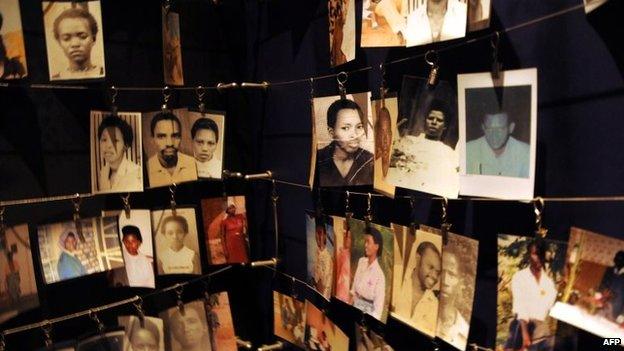

There are numerous memorials around Rwanda to those killed in the genocide

The Rwandan government is said to be "furious" with Britain, as much for the style in which the arrest was made as the substance of the indictment itself.

Broadly speaking, Rwanda's view is that the Europeans, by issuing an arrest warrant, have been hoodwinked by pro-Hutu sympathisers.

It feels energies should be better channelled into chasing the Hutu militia - known as the FDLR - still wreaking murderous havoc in the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo, rather than pursuing alleged war criminals from Rwanda's troubled past.

It is a well rehearsed argument.

When Britain temporarily suspended direct budget support to Rwanda in 2012, following allegations by a UN group of experts that Rwanda was funding the Tutsi-dominated M23 militia waging war in eastern DRC, it also suggested its long-term friend had been influenced by genocide deniers.

Rwanda is still deeply haunted by its past and European leaders, who acknowledge they didn't do enough to intervene in one of the worst atrocities of a generation, are silenced.

Some two million people fled into DR Congo (then Zaire)

Britain is Rwanda's biggest bi-lateral donor contributing £66m a year in aid to Rwanda.

That figure swells to nearly double when European contributions are added.

British businesses are increasingly looking for new investment opportunities in Rwanda from real estate to mining to financial services and the conservative "wealth agenda" in Africa has put Rwanda centre stage.

But Britain is often criticised by some activists for pursuing a policy of wealth creation at any price - not doing enough to challenge President Paul Kagame's human rights record in his dealings with his opponents and the media.

'Extremely embarrassing'

Andrew Mitchell - Britain's former international development secretary - for whom Rwanda has become something of a poster boy for development - has been the most outspoken on the British side so far, since Gen Karake's arrest.

He told me it was "extremely embarrassing" that the intelligence chief was arrested during "official diplomatic business" and said that he and others were still trying to figure out "why now?".

General Karake is a frequent visitor to the UK and has been for many years.

Twitter users have suggested that the arrest of such a prominent figure is "revenge" for a recent dispute with the BBC, following a controversial This World current affairs programme questioning the historic record of the genocide.

This is patently not true as the BBC has no influence over European arrest warrants or the police. But it does beg an important question.

How does Britain navigate a relationship based on trust and mutual respect, when the execution of a European Arrest Warrant is seen by some in the Rwandan leadership, not as a legal practicality but the ultimate act of betrayal?

- Published23 June 2015

- Published4 April 2019