Tunisia attack: Foreigners and locals lament dwindling tourism

- Published

Beaches near the crime scene in Sousse stand nearly deserted at the peak of the tourist season

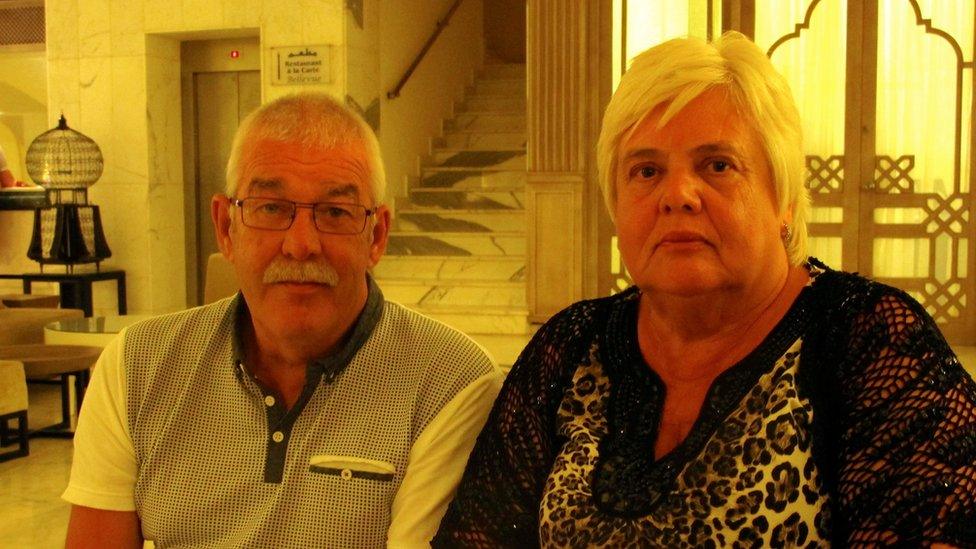

Glynis and Dave Clark, 60 and 58 respectively, did wonder whether to cancel their holiday or change their destination.

The holiday was booked for Hammam Sousse, where 38 people - most of them British - were murdered a week ago. Remarkably, they thought it wouldn't be fair on the Tunisians not to go.

"I immediately looked on Google Maps where our hotel was and realised it was right next door [to the crime scene]", Mrs Clark says. "My first reaction was that I didn't want to come, it was too horrific.

"But when you take time to think about it, you realise it could have happened in any beach in any country."

The British couple, from Nottingham, are no stranger here. This is the third time that they've come to Hammam Sousse. They first came in 2013 and decided to return in April this year to celebrate Glynis's 60th birthday.

"It's lovely here. The people are so warm, so friendly - they didn't deserve this," Mrs Clark says.

Glynis and Dave Clark were determined to stick with their holiday plans in Sousse in spite of the attacks

Hotel workers have been losing their jobs ever since the attack happened, as Rana Jawad reports

Travel agency Thomas Cook offered the couple a refund or an alternative holiday in Turkey or in Egypt but they declined the offers.

"It's an absolute bloody shame to find the hotel empty," says Mr Clark, who spent 22 years as a ground crewman in the Royal Air Force and is now working part-time at East Midlands airport.

Empty trains, empty streets

Thousands of tourists have left since the attack happened.

Jeblai Bouraoui and his colleagues wait in their tourist trains, a few steps away from the beach of Sousse, but no-one shows up.

"We've been here for almost two hours," he says. "I even fell asleep!"

During the month of Ramadan, snoozing is an easy trap for those who fast but aren't keeping busy.

"There was no time for that a week ago," Mr Bouraoui says. "We would do return trips after return trips without a break. We only ran one ride this morning."

That's one ride for seven passengers. Waiting for more to come along runs the risk of losing those seven to impatience.

Jeblai Bouraoui (in yellow) and his colleagues would normally be ferrying hundreds of tourists in their beach trains

At about 3.5 Tunisian dinars (£1.15), a return ticket to Port El Kantaoui, less than 15km (10 miles) further along the coast, Mr Bouraoui doesn't even need to count how much they've made so far. He opens his belt bag: it's almost empty.

Tourists have also deserted the main commercial street of the city. In the historical medina quarter, which has long been turned into a tourist shopping maze, there are no sunburnt faces to be seen.

The narrow streets are usually so overcrowded that it is hard to move. The newfound tranquillity would be enjoyable if it weren't a reminder of a sombre reality, a mass murder that sparked a tourist exodus.

Will the tourists return? "Each day that passed since the attack happened, there are fewer customers," says Naoufel Barhoumi.

Mr Barhoumi owns two shops almost facing each other; he sells bags, wallets, sunglasses, bracelets, necklaces and beach towels.

"I only sold one bag today and that was to a Tunisian woman," he says. "We try to remain optimistic but we are already seeing the consequences of the attack."

Shopkeeper Naoufel Barhoumi's business has fallen off sharply in the wake of the attacks

Walking past is Sylvie Quainay, 53, from France, who arrived the day after the attack. Unlike the many thousands of tourists who booked their holidays through a tour company, Ms Quainay has rented a house for the whole year. This is her third time here in six months.

"I am suffering from arthritis so I come here to find a better weather and bathe in the sea because the combination of dry heat and salt is doing me good," she says.

"What happened is terrible because life is sweet for us here and relaxed. Why should I stop coming? There is nothing we can do. It could have happened in Paris too."

Showing solidarity

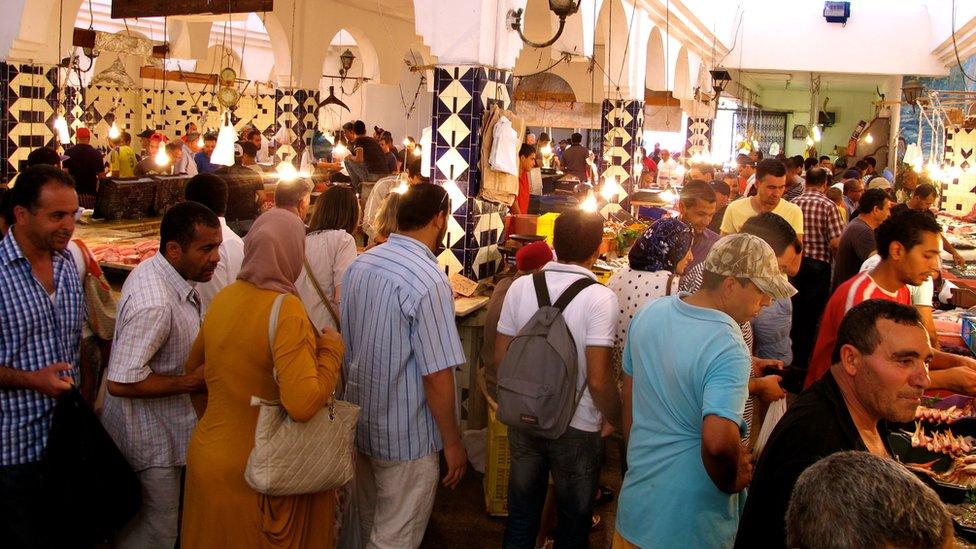

A few winding streets away, the small, covered market is bustling but there is not a tourist in sight. The people here are all Tunisians who have come to shop before they can break the fast later on.

Marouen Dhia and Marouen Rekais are cutting massive chunks of almond or pistachio nougat into smaller bites - a local speciality that residents wouldn't miss during Ramadan. They are busy and smiling.

"This is a delicacy we sell only one month a year during Ramadan," says Mr Dhia. "Tourists would buy some but our main clientele is local."

The market in Sousse is down on its usual number of tourists

Back on the main beach, most hotel sunbeds are left empty. A couple of elderly people have gone for a guided horse ride but the volleyball pitch has been deserted and no-one is playing football.

At the El Mouradi Palm Marina hotel next door to the crime scene, where Mr and Mrs Clark are staying, the number of clients has fallen from more than 600 last week to a little more than 100 today.

Mid-July is usually the peak of the tourist season but dozens of people have now cancelled their reservations at the Palm Marina.

"We are disappointed that the hotel isn't full for the people here because this is their livelihood," says Mrs Clark.

"The best way to show solidarity with these people is to come on holiday here," adds her husband. "If people come back, those behind the attack will have lost the battle."