Can Fifa end child trafficking from Africa to Asia?

- Published

Children from West Africa have ended up in Laos

Fifa made a little-noted amendment to its statutes earlier this year but it was one that deserved considerably more attention.

Football's world governing body decided to lower the age limit, external for international transfers to include players aged 10 and above. That's right: 10.

Before the change was introduced in March, clubs only needed to go through the official process of applying for an International Transfer Certificate if their target was at least 12 years old.

"The executive committee decided to reduce the age limit… due to the increased number of international transfers of players younger than 12," Fifa told the BBC in a statement.

'Unscrupulous'

But what happens when clubs simply start recruiting six, seven and nine-year-olds to bypass Fifa's new red tape?

Well, if that does happen, Fifa says the age limit "could be reconsidered" if it detects a trend of players even younger than 10 being transferred.

Nonetheless, the change of the rules highlights the growing problem of the illegal movement of minors.

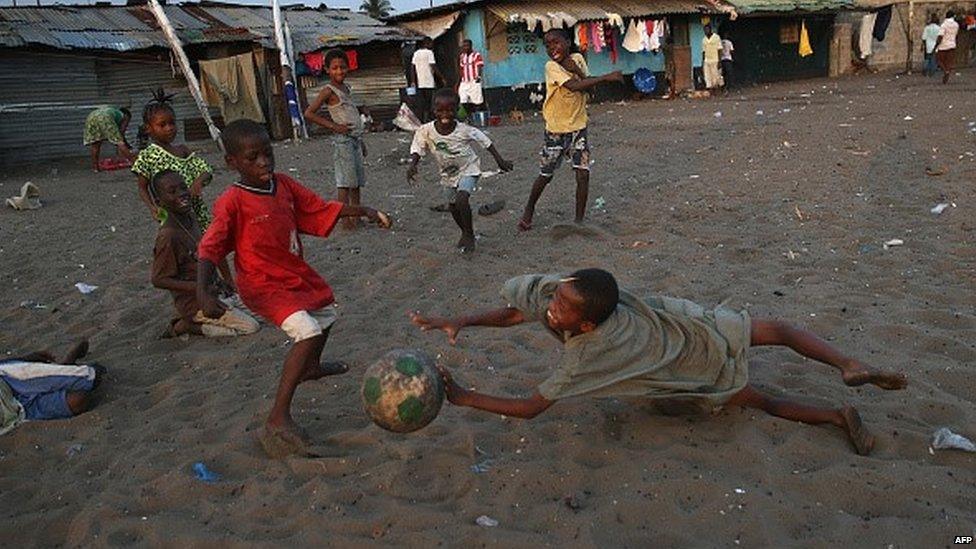

Football is the most popular sport in Africa

The Paris-based non-governmental organisation, Foot Solidaire, helps send boys back to Africa after they have been tricked by unscrupulous agents and empty promises into leaving the continent.

It estimates that 15,000 teenage footballers are moved out of just 10 West African countries every year - many of them underage.

Jean-Claude Mbvounim, Foot Solidaire's founder, says that agents can pocket anywhere between $3,000 (£2,000) and $10,000 for each child they send to a fictitious trial at an imagined club - and says football needs help to combat the issue.

"Fifa has to do more with public authorities, governments and civil society because this issue is a social issue," says Mbvounim.

"Today we have criminal activists threatening world football and the young players, so it's important to work together. Fifa will have to be on top of this battle."

Twenty-three underage players were imported to Laos from West Africa

Some of the original party returned to West Africa after help from players' union Fifpro

What makes the actions of Champasak United in Laos, who imported 23 underage players in February, interesting is that they are the actions of a club, albeit under the guise of an academy.

The normal story is that teenagers duped into leaving Africa end up on the streets of whatever country they have been sent to, since the 'agent' has disappeared and no club is aware of their presence.

'Unrealistic goal'

According to the boys who went to Laos and have since returned to Liberia, thanks to the help of global players' union Fifpro, Champasak's academy lacks a proper coach, medical facilities and there is no provision for education.

The club's player-'African players manager' Alex Karmo admits Champasak brought in the players to sell them on at a profit afterwards.

The contracts they offered the youngsters enabled the club to pay them absolutely nothing should they want to, although Karmo says they were paid each month.

The signed deals also stated that players must pay back the cost of their flights from Africa, and all food and accommodation received, should they wish to break their contract - an unrealistic goal for players earning zero a month at worst and $140 at best.

The Liberians are not the first Africans to be disappointed, but their nation is one of the few in West Africa to have no football academy, even if the Liberian FA says it plans to open one later this year.

To put it into context, the youngsters were keen on Laos even though it has made next-to-no impact on the international stage and is ranked 16 places below 161st-rated Liberia in Fifa's national rankings.

"Liberia is over 165 years old and we are just completing the first football training centre," said the country's FA chairman Musa Bility.

"Maybe if that training centre was here, those kids would not be in Laos."

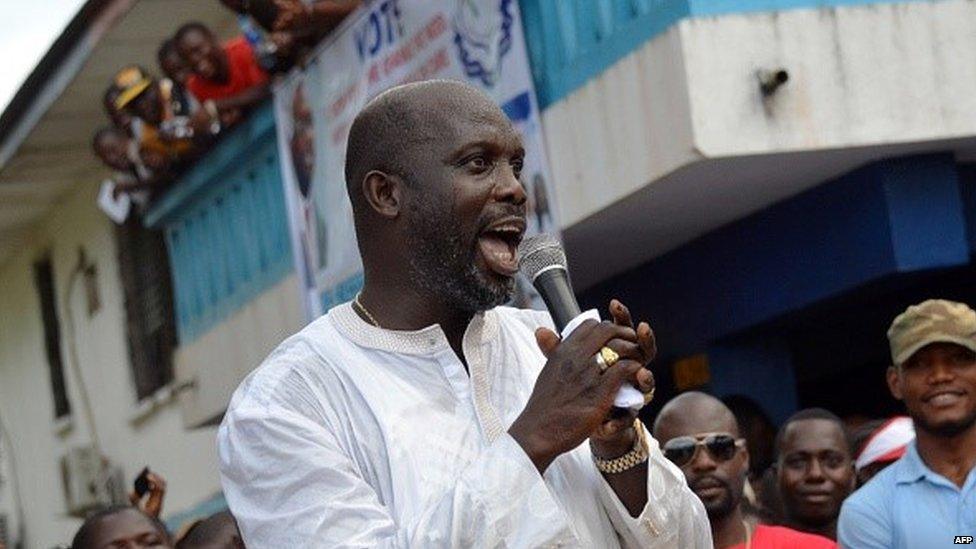

George Weah was one of Africa's most famous footballers

The plan is to have former Liberian football star George Weah as a title name for the academies, but can their presence stop the flow of young players abroad?

As another potential form of defence against this problem, Foot Solidaire is looking to open an observation centre in the Senegalese capital Dakar next year. It hopes to both inform youngsters and families of the perils of trafficking, as well as keep a close eye on the exodus of West Africa's youngsters.

- Published21 July 2015

- Published21 December 2015