Tunisia beach attack: What's the security situation?

- Published

A month on from the armed attack that killed 38 people, 30 of whom were British, in the resort town of Sousse, the Tunisian government is still grappling with its security responses to the threat of terrorism.

The UN estimates 5,500 Tunisians (1,500 more than previous estimates) have joined the ranks of IS in Iraq and Syria, the self-styled caliphate's largest contingent of foreign nationals.

Of these, about 500 have returned and are under surveillance, and a further 15,000 have been prevented from leaving to join IS.

The threat is also regional, as an estimated 1,500 Tunisians have attended jihadist training camps in neighbouring Libya, while a third (11) of the group that attacked the In Amenas gas plant in southern Algeria in January 2013 were also Tunisian nationals.

Tunisia's international partners, including the UK, have offered advice and technical assistance in counterterrorism, security planning and training, but no new funding.

Something more than prevention is now needed to tackle the deeper socio-political and economic roots of Tunisia's current malaise.

What was the security situation like before and after the Arab Spring?

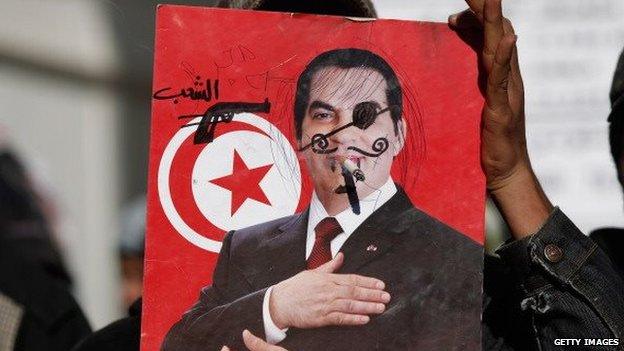

President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali had a background in policing and ran Tunisia effectively as a police state from the late 1980s.

From the early 1990s, the Islamist movement, which re-emerged as the Ennahda party in 2011, was banned, and its members subject to long prison sentences and/or exile.

The Tunisian army has never played as strong a political and security role as in neighbouring Algeria, although the senior military command was instrumental in hastening President Ben Ali's departure from Tunisia in January 2011.

Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali led Tunisia for 23 years before he was ousted in 2011

A number of senior Ben Ali-era officials and police commanders were dismissed and/or arrested following the Arab Spring, leaving Tunisia's security institutions and Ministry of Interior prey to political infighting over new appointments and the pace and direction of internal reforms, above all within the police force.

The period from 2011 also saw the rise of the Salafist Ansar al-Sharia group, which the first post-Arab Spring elected government, led by the Ennahda party, was initially hesitant to rein in.

Following two high-level political assassinations, and the growing infiltration of weaponry and violence from neighbouring Libya, Ansar al-Sharia was outlawed as a terrorist organisation in 2013.

The Tunisian army has also needed the assistance of the Algerian army in combating a jihadist insurgency in the Chaambi mountains on their common border, while regional terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) have increased their inroads in the coastal hinterlands of southern and western Tunisia and in jihadist training camps across the country's porous border with Libya.

As the influence of IS has grown in neighbouring Libya since early 2015, so has its attraction among already radicalised Tunisian youth.

What was the situation at the time of the Sousse attack?

Tunisian security forces stand in front of the Imperial hotel on the day of the Sousse attack

In the wake of the terrorist attack claimed by the AQIM offshoot group Okba Ibn Nafaa on the Bardo Museum in Tunis on 18 March 2015, the Tunisian authorities issued assurances they would deploy at least 1,000 more security agents to tourist sites.

It later emerged that the Sousse attacker, Seifeddine Rezgui, had been linked to the main organisers of the Bardo attack and trained with them in Libya, but had not been under police surveillance.

In the weeks preceding the Sousse attack, an IS declaration expressly warned "Christians" from taking to the beaches of Tunisia during the holy month of Ramadan (from mid-June to mid-July 2015) but made no explicit threat on the region of Sousse itself.

What has changed since?

More armed security personnel have been deployed at hotels and beaches

The Tunisian government has declared a nationwide state of emergency and deployed extra security personnel to tourist resorts, many of whom are armed.

It is also building a 160km (100-mile) wall along the most vulnerable section (comprising approximately a third) of Tunisia's southern border with Libya, due for completion in the early autumn of 2015.

New anti-terrorist laws are due to be approved by the end of July 2015.

The governor of Sousse and corresponding local police chiefs have also been removed from office.

Reforms within the Ministry of the Interior to speed up the response to future threats have been slower.

Plans to restructure internal and operational command structures are continuing, while the key ministerial post in charge of national security for the police has remained vacant since the dismissal of its former incumbent in March 2015 following the Bardo attack.

Is this a one-off case or could it be seen elsewhere in the Maghreb?

The focus on the role of IS as having inspired the Sousse attack has highlighted the influence of events in the wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region on developments in the Maghreb.

However, for a number of years the region has also been subject to greater trans-nationally co-ordinated terror attacks by residual and offshoot al Qaeda-inspired groups, involving multiple nationalities, and with a reach into and across the impoverished and weakly policed states of the African Sahel regions to the south of the Maghreb.

Tunisia's democratic transition since 2011 has made it a particular target of armed groups and ideologies opposed to its alliances with Europe and the US, and its economic dependence on tourism as a source of foreign revenue.

Only Morocco has similar levels of foreign tourism, but it has better-equipped intelligence and security services than Tunisia.

A four-day siege took place at the In Amenas gas plant in southern Algeria in 2013

Foreign nationals have been explicit terrorist targets in Algeria, where 37 foreign workers were killed at the In Amenas gas plant in January 2013 and a French tourist decapitated by an IS-affiliate group in September 2014.

The ability of small armed groups to train and operate across the whole Maghreb-Sahel region argues in favour of co-ordinating a region-wide response to this shared threat, especially while Libya remains essentially an ungoverned territory.

Unfortunately, at the heart of the region, Algeria and Morocco remain politically divided and do not co-operate over security issues.

The main regional security challenges to outside policymakers will be to work on overcoming this deadlock.

Claire Spencer is senior research fellow for the Middle East and North Africa Programme and Second Century Initiative at Chatham House, external.