Cecil the lion: Why a hunting ban is not the answer

- Published

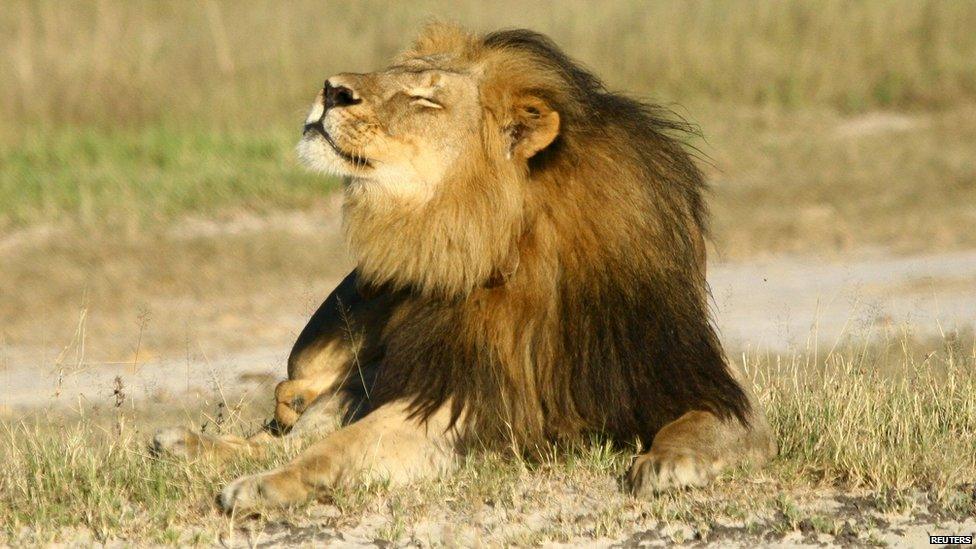

Cecil was skinned and beheaded after he was shot last month

Three little spots on a cracked smartphone screen show Brent Stapelkamp the last known locations of Jericho the lion.

Every two hours his tracking collar pings the satellite and it's clear on the map that the lion, who was Cecil's buddy, has left the protection of Hwange National Park and ventured onto private hunting land.

It's the same place where Cecil was killed and Jericho, who led the pride with him, has spent a lot of time there recently - calling for his friend.

Brent, who is a field researcher with Oxford University's Wildlife Conservation Research Unit,, external had been following Cecil for nine years and it was he who discovered the lion had been killed.

"When he's walking it's a long line of dots on the map, but if he's been eating something it's in a big cluster," he said.

"The fact he had been eating before his collar switched off gave me that sense that he had been on a bait."

'We have to be careful'

The last known position was enough to lead the authorities to Cecil's remains.

A railway line is all that divides the park from private hunting land. There's no fence or barrier and as we watched, animals were coming and going easily across the track.

Hwange National Park is home to many animals, sought by hunters

The professional hunter who led Walter Palmer's now infamous expedition is on trial - and the man who owns the land may face charges of allowing a lion to be killed without a permit.

Hunting some of the big game animals, including lions, has been suspended around Hwange, while the quota system is investigated.

This, along with the international outcry, means Jericho is safe for now.

His cubs also seem to be alive and well. Just before dawn two females and their young crossed the road ahead of us, close to the area that had been Cecil's territory.

The international reaction to the killing of the famous lion has sparked fierce debate over whether "trophy hunting" should be banned.

But there's little debate here, even among conservationists.

Hunting has been temporarily suspended around the park, offering some species a reprieve

Brent Stapelkamp's position is not surprising: "Personally I don't want to see lion hunting ever again - just because of the way lions react to it."

But he doesn't want it banned.

"Hunting can be a valuable component to conservation. If a property has a hunting quota and that money comes back from hunting into the management of the land, it's not going to be at risk," he said.

"So we have to be careful. The world reaction might polarise things and hunting might be banned outright.

"I think we have to be very cautious about how this momentum can be used."

A greater threat

Protected animals cannot be killed. For the others, hunting quotas are set - typically at 0.5-2% of the population in any given area.

If the system works properly the money is used to fund the national park, to pay rangers and protect animals.

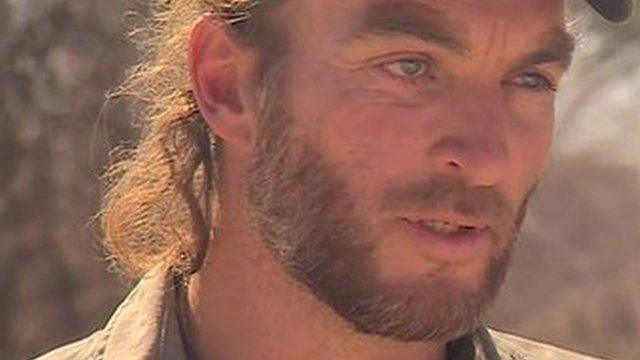

Researcher Brent Stapelkamp says he opposes a hunting ban, despite Cecil's death

Trevor Lane from the Bhejane Trust, external conservation group says there is a far greater threat to the land from poaching.

This can either be from commercial poaching for elephant tusks or rhino horns - or subsistence poaching by impoverished local people snaring a deer to eat, but killing big game as well.

"If we took the hunting out of those areas without offering an alternative, they would be poached out within two years. There would be nothing left," he said.

"The hunting brings in revenue. I know it's a terrible thing to some people, but we have to be practical and we have to be realistic here.

"Whether we lose a few animals, which pays for the conservation, or whether we lose the whole lot is the option faced in many areas.

"We just don't have the finance or the ability to look after those areas. If there was an alternative I'm sure everyone would look at it."

Professional hunter Theo Bronkhorst says the case against him is "crazy"

Many here hope the outcome of the investigation and the attention to the system will mean better protection for the animals, but it all comes down to funding.

"There's a general agreement our current regulations and statues suffice, but maybe we have to do more in terms of monitoring and enforcement," said Edison Chidziya, director general of Zimbabwe National Parks and Wildlife Management.

The global focus on Cecil has brought the whole industry together. There is optimism it will tighten regulations and squeeze those who have been breaking the law.

But by focusing on trophy hunters above all else, public opinion is perhaps missing a bigger point.

Poaching is driving many species towards extinction and there are other parts of the hunting industry here and across Africa that would benefit from closer scrutiny.

- Published4 August 2015

- Published29 July 2015

- Published5 August 2015

- Published6 August 2015

- Published30 July 2015