Pressure mounts for political solution in Libya

- Published

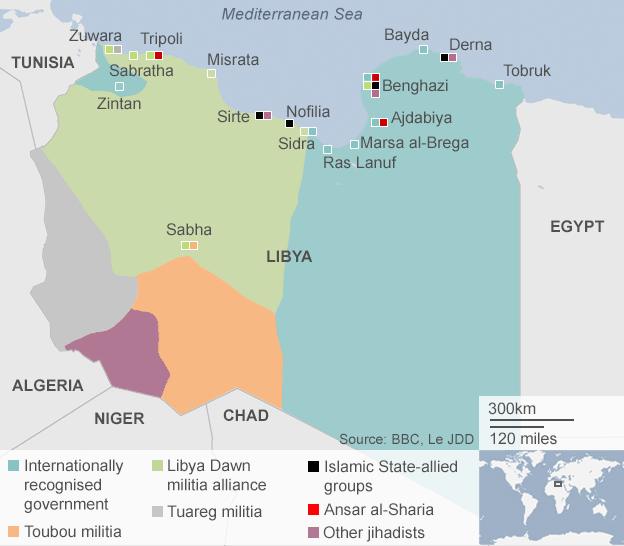

Libya remains riven by different factions

A UN-led attempt to broker a deal that would usher in a new Libyan unity government has been going on for nearly a year.

Libyans are facing increasing pressure from the West to reach an agreement, with the migrant crisis adding to the clamour for a positive outcome.

The envisioned Government of National Accord has been promised unreserved support by some key EU players, including the UK, Italy and France.

Protracted dialogues in times of conflict are nothing new, but they become excruciatingly difficult to steer when there is no dominating political movement or military force. And in this case there are multiple players.

All sides are vying for a resolution that is either completely in their favour, or gives them a slight edge over their counterparts.

For the past year, the East has housed an elected parliament in Tobruk that is internationally recognised but has no real power beyond what the armed factions who back them permit.

The capital, Tripoli in Western Libya was overrun by a loose alliance of militias that resurrected a former parliament, which installed its own cabinet.

The South is a place no-one really wants to talk about, though it has witnessed some of the deadliest tribal clashes to date and is a free-falling gateway for all things illegal.

All this also provided fertile ground for the militants of the so-called Islamic State to rise and mushroom the past 10 months.

Mandate ending

The Tobruk parliament's mandate ends in October, and there are worries that another big confrontation over control of the capital is looming if the term ends before a political agreement is reached.

Some believe that certain Libyan blocs in both camps are stalling the process precisely for that reason, with even more political and military posturing inevitable.

But this is Libya, and there are observers who argue - for good reason - that a bigger confrontation between rival militias could also be triggered if a deal is rushed.

Ahmed El-Abbar, an independent politician taking part in the dialogue, is eager to see a deal.

He said: "The fear of creating a constitutional power vacuum come October is what is now making all the parties involved expedite the process of reaching an agreement."

He remains hopeful because they have no other choice.

"The country is approaching several crises now, whether it's economical or even social."

The latest draft agreement, external was initialled by most of the political stakeholders, external in late July, but only after controversial points in it were annexed.

Since then, the Tripoli-based parliament, known as the General National Congress, has practically withdrawn from the talks.

A day before last week's round of talks in Morocco, the chief Tripoli representative at the talks resigned, external.

Ominous signs

Deep rifts within the two main political camps do not bode well for any agreement.

The Tobruk-based government has called for international assistance to fight extremism

Meanwhile, opposing sides in Libya's conflict are building up their forces and making unilateral statements that suggest they have other self-serving plans.

There have been locally-led ceasefires in some parts of the country, and some believe this provides hope for a broader "Libyan solution".

But who could lead a unity government?

It does not appear as if anyone really has a clue at the moment. But that is what will be tabled this month when all sides submit a list of candidates.

Ideally, the country needs a unifying figure; someone who is politically and ideologically neutral and willing to risk life, limb, and shelter every day until a national force that is loyal to his government is forged.

Western hopes

Western nations, like the US, UK, France, Germany, Italy and Spain are banking that a new government of unity would ask them for help to stabilise Libya.

A European diplomat told me they envisioned establishing a "safety zone" in the capital that would protect foreign diplomatic missions using a foreign force.

Khalifa al-Ghawi runs the government based in Tripoli

That coalition would also simultaneously train a Libyan force to protect the government and its institutions.

But try asking foreign diplomats and Libyan politicians about where the "new" Libyan force candidates would be drawn from. You could hear a pin drop.

"We are looking for a minimal international footprint. We don't want to find ourselves in a position where we are drawn into combat," I am told.

But this plan is in its very early stages too.

Italy is envisioned to be the "framework nation" that would draw together the coalition.

"But we haven't even sorted out who would be a part of any foreign force," the diplomat explains.

So like everything else in Libya, there is a timing issue, and at this stage, it is on no-one's side.

- Published27 July 2015

- Published20 January 2015