How will a population boom change Africa?

- Published

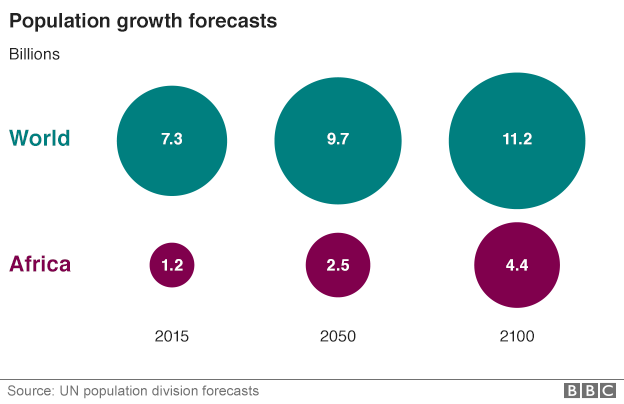

The United Nations estimates that Africa's population will double to 2.5 billion by 2050. About 400 million of these people will live in Nigeria alone.

Four experts tell the BBC World Service Inquiry programme how this population boom will change Africa.

John Wilmoth: Putting the population in perspective

John Wilmoth is director of the population division of the United Nations.

"The statistics give you a certain perspective on the world. You see these grand trends of history through demography, birth and death and when people become married and when they move.

"There's been a substantial reduction in the death rate in Africa, like in other parts of the world, and this is good news in many ways - children survive in much greater numbers to adulthood and adults survive to old age.

"However, what's preventing that kind of movement in a similar direction to what's happening in the rest of the world is our continued levels of high fertility.

"You always have three things together: you have high fertility, rapid growth and young populations.

"Currently in Africa we estimate that 41% of the population is under the age 15. This is a very high fraction. Another 19% are between ages 15 and 24. So if you add those two together you've got three-fifths of the population that is under the age of 25.

"We really need political will at the highest levels paying attention to this issue because it really will affect the ability of those countries to raise the standard of living for their populations, and it will have long-term implications for the well-being of that part and the rest of the world as well."

Obadiah Mailafia: We must improve infrastructure and create jobs

Obadiah Mailafia is the former deputy governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria and former presidential adviser.

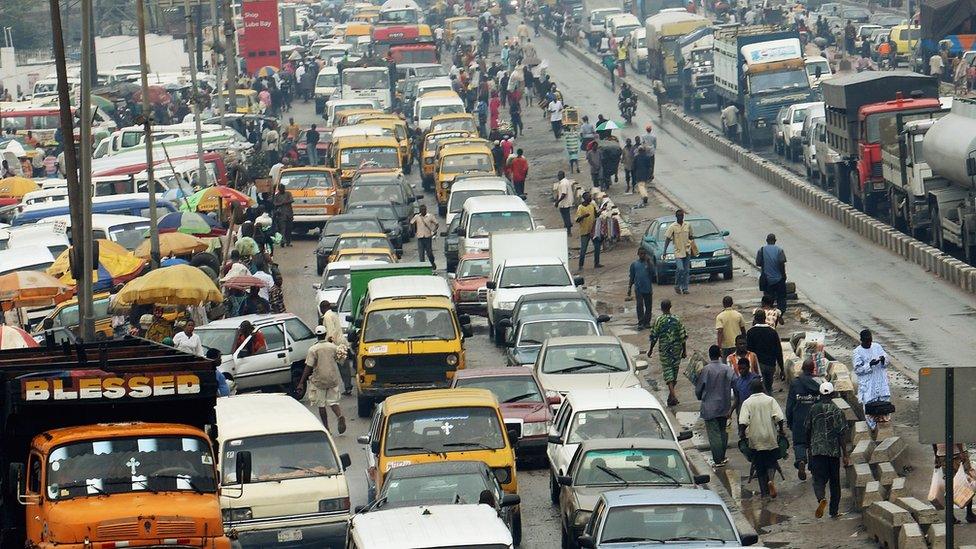

"If you go to many of our cities these days they're much more crowded than ever. So huge challenges are deriving from the population increase, and it is quite palpable. You could see it not only in heavy traffic, but also pressure on social services, the water, electricity, schools and the rest of it.

Traffic in Lagos, Nigeria

"From an economist's point of view, it's often the case that increase in population is synonymous with increase in GDP, because you have more labour force, more consumption, more spending.

"So it tends to be reflected in an overall rise in GDP. But in this day and age quantitative growth is not enough. It's not the ultimate indicator of better conditions for citizens.

"In some of our biggest airports, there is now pressure on space for parking of private jets. And yet the streets are booming with poor people, people hustling in the streets because they have no opportunities and no hope for the future.

"My worry is the fact that we are not making arrangements to cater for this rising population.

"There's no country in the world that I know of that has over 70 million people that does not also have a flourishing rail network. The roads are cluttered up with heavy trucks. And also expanding social services like health, education and the rest of it, all those things need to be in place, together with better planning for population and for families.

"We must create jobs, we must expound opportunities for young people to get them engaged and busy, otherwise we might find that the sort of thing that happened in the Arab Spring could happen in Nigeria."

Hans Rosling: Population growth isn't the problem - extreme poverty is

Hans Rosling is professor of international health at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden and perhaps the world's best-known statistician.

"What is difficult for the surrounding world is to realise that Africa will become a much more important part of the world. And I see that because so many big investment banks invite me to come and lecture because they see, 'Wow! There's economic growth in Africa. Wow! Companies in Africa are profitable today.' They see customers.

"The reason the population is growing in Africa is the same reason that [saw] population growth first in Europe, then in the Americas, then in Asia. It's when the population goes from a phase where you have many children born and many who are dying. Then the death rate goes down and [some time later] the birth rate follows.

"We have a possibility that Africa will repeat what Asia did: a very fast transformation where once you had education, you had child survival and parents saw the options of a better life for their children, they [would] choose to have two or three. And that is happening in Africa; in fact it's already happening among the better-off in Africa.

"Addis Ababa (the capital of Ethiopia) has 1.6 children per woman, which is less than London. So when you hear an average of Africa of 4.5 children per woman, that is composed by the most modern part of Africa with two children per woman [or less] and the still worst-off, in very extreme poverty, with six to seven.

"I can see government after government in Africa getting it. Presently we see Ethiopia, Rwanda, Ghana doing the right things and others are coming fast.

"If you continue to have extreme poverty areas where women given birth to six children and the population doubles in one generation, then you will have problems. But it's not the population growth that is the problem - it's the extreme poverty that is the underlying reason."

Isabella Aboderin: We need to invest in the young AND old

Isabella Aboderin is a senior research scientist at the African Population Health Research Centre in Nairobi and associate professor at the Centre for Research on Ageing, University of Southampton.

"Africa is a young continent. It will remain the youngest region worldwide. However... the number of older people is going to grow more rapidly in sub-Saharan Africa than in any other place on this globe.

Sub-Saharan Africa has to contend with a rapidly ageing population

"Once you have reached age 60, you still have an expectation of living 16 to 18 years longer in sub-Saharan Africa and that's actually not that much different than in other parts of the world.

"So it's a life expectancy at 60 that's already considerable and it's the youth bulge that Africa is now experiencing that is going to age. So all these children and youth that you have now in the next three, four, five decades, they will have reached old age and there's a real need to prepare societies for that.

"Because the resources are constrained, the middle generation has to weigh up often between investments in children's education and investments in supporting older parents. And, in these kinds of situations, priority is usually given to the younger generations.

"At the moment, there is very little, if any, focus on the older population. There appears to be an assumption, mostly implicit, that the older population is unproductive, has nothing more to offer and is strategically irrelevant and I think this is something that one needs to challenge and needs to look at very carefully.

"It's not a zero-sum game. It's not about investing in older people [and taking] resources away from the youth, it's rather seeing that they are linked. Investing in older people today means enhancing their capacity to contribute to the empowerment and the education and the employment opportunities of youth today."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 12:05 GMT/13:05 BST. Listen online or download the podcast.

- Published29 January 2014

- Published13 September 2012

zz.jpg)

- Published1 September 2015