Head-to-head: Is Africa’s young population a risk or an asset?

- Published

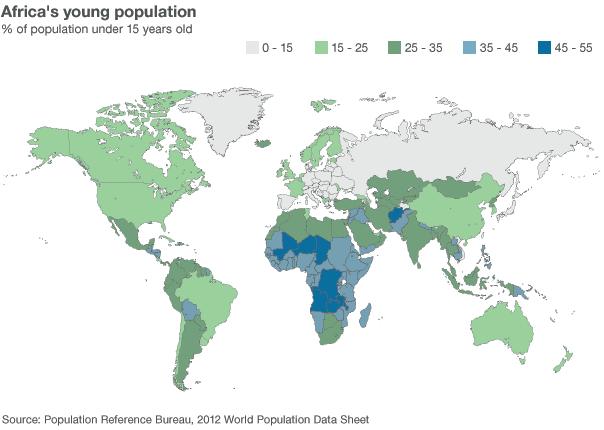

Africa has more people aged under 20 than anywhere in the world and the continent's population is set to double to two billion by 2050.

Two analysts put forward rival arguments about what this means for the Africa.

Researcher Andrews Atta-Asamoah believes it poses a major challenge unless properly managed, while below economist Jean-Michelle Severino argues it is a massive potential work force that can drive development.

Andrews Atta-Asamoah:

Walk into many cyber cafes in West Africa and you will see scores of young minds running sophisticated counterfeiting schemes aimed at making money by defrauding innocent people.

They blame unemployment and lack of opportunities for driving them into entrepreneurial criminality.

Their stories are similar to those of the young people who wait at secret North African ports for an opportunity to reach Europe by boat.

They are also similar to those who have ended up in the ranks of the Somali Islamist group al-Shabab, because they were promised salaries by their recruiters when there were not any more conventional job offers.

Such realities illustrate the threats associated with Africa's growing young population.

Sub-Saharan Africa is a region where people aged between 15 and 29 will continue to constitute about half of the population of most countries for the next three to five decades.

Currently, the estimated median age in sub-Saharan Africa is under 19.

There is a strong case to be made that a young population, or a poorly managed young population, leads to instability and civil conflict.

The terrors of the Mungiki sect in Kenya; al-Shabab's blood-thirsty young fighters in Somalia; the horrors of Boko Haram attacks in Nigeria and the emergence of several Islamist groups in Mali and its neighbours.

These are all groups essentially driven by young people.

The civil wars across West Africa during the 1990s and early 2000s were also fuelled by disproportionately young populations with not enough to do and not enough money.

'Lawless enclaves'

Violent crime in South Africa is among the highest in the world, alongside youth unemployment.

In contexts where the growing youth population have suffered political exclusion and economic marginalisation, as was the case with the Arab Spring in North Africa, the situation can even be a recipe for revolution.

Even within a peaceful environment, a rapidly growing young population presents a major challenge.

In cities such as Ghana's capital, Accra, Nairobi in Kenya and Nigeria's economic hub of Lagos, the impact of the continent's growing young population is noticeable.

Living in the city is fashionable among young people - but the consequent rural-urban rush has resulted in unmanaged settlement characterised by mega slums such as Kibera in Nairobi, Sodom and Gomorrah in Accra and Makoko in Lagos.

Such settlements are often lawless enclaves where police presence is limited and service provision an afterthought.

A growing young population promises opportunities.

But it is increasingly becoming clear across Africa that unless political leadership offers young people something to live for, social stresses such as unemployment can make them easy prey to those who offer them something to die for.

It is therefore important that in seeking to harness Africa's demographic dividend, the right leadership and prudent policies are prioritised.

At the moment, in too many countries, that is not the case.

Andrews Atta-Asamoah is a senior researcher for the Institute of Security Studies in South Africa

Jean-Michel Severino:

Does demographic growth work for economic growth? Yes.

Or at least, at some specific moments, one of which Africa is experiencing now.

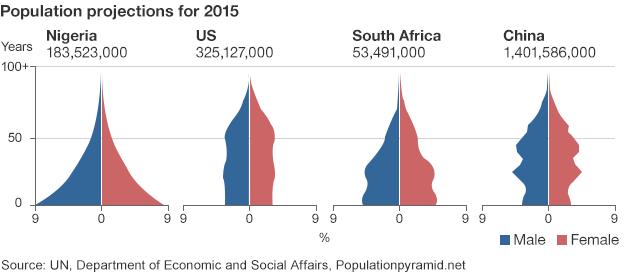

This continent's path is unique in the history of humankind for the speed at which it has enjoyed the growth of its population, and probably, the speed at which it will experience its decline.

For more than 50 years, up to the late 1990s, birth rates exploded in what was an empty continent and the impact on economic growth has been severe.

The weight of the young generation on the shoulders of the relatively few adults dragged down economic growth rates.

Limited domestic demand and lack of infrastructure prevented the growth of strong local markets.

The collapse of raw material prices in the early 1980s created a huge burden of debt for the continent, as well as dependency on aid and raw material exports.

But this is changing.

The decline of fertility rates following a period of rapid growth presents huge economic opportunities and has started to launch Africa on a very long-term growth pattern.

This very specific period, known by economists as the "demographic dividend", is Africa's moment.

Each year, the increasing number of working-age adults carries the weight of a relatively diminishing proportion of children, whilst elderly dependents remain few.

This favourable moment is compounded by the energy of a youthful population.

It is also multiplied by other important trends, all linked to this specific demographic moment.

Surge in domestic firms

The higher density of the population allows domestic markets to be created, demand to emerge and local firms to develop in an economic environment that is more business-friendly than 20 or 30 years ago.

The relative cost of infrastructure declines.

The proportion of the population living in cities also increases, with all the productivity gains this carries.

Urbanisation is one of the most powerful growth engines the world has ever experienced.

Of course, the impressive economic growth rates the continent has enjoyed since the turn of the century are still insufficient to really catch up with high-income countries.

Of course, economic growth in Africa remains linked to the price of commodities.

That said, many land-locked countries with few natural resources have enjoyed fast growth in the past decade - and commodity prices do not entirely explain the surge of domestic firms that one sees across the continent.

Telecom services and improved education have also played an important role in boosting the productivity of the economy.

Of course this will have an end.

There will come a time, which Europe and Japan are experiencing now and so too will China, when a smaller and smaller proportion of working-age adults have more and more elderly dependents to support.

This is an age when economic growth is more difficult to maintain.

Africa will enter that time, for sure - but possibly not for another century.

Jean-Michel Severino is a former head of France's international development agency, the Agence Francaise de Developpement and author of Africa's Moment.

- Published31 October 2013

- Published15 November 2012

- Published21 November 2013

- Published14 November 2012