Why South Africa's born-free generation is not happy

- Published

A new black consciousness movement is emerging in South Africa 21 years after its first democratic elections - most recently seen in nationwide student protests. The BBC's Alastair Leithead considers if this marks the end of the idea of the "rainbow nation".

The trendy bars and clubs of Braamfontein in downtown Johannesburg are not the melting pots of race and culture you might have expected.

Most places are all white or all black.

The coming together of the nation Nelson Mandela worked so hard for appears to have stalled.

The "rainbow nation" he spoke so much about is being seen as a failed project by many young, particularly black, South Africans.

The voices are loud and while not all are predicting doom, they are demanding change.

More change than South Africa has given them in its first 21 years of democracy.

Born free, pay later

Why now?

Perhaps it is because the first generation of those black South Africans who were "born free" - after the end of apartheid in 1994 - are coming of age.

They know the story of the struggle but they do not see what history has given them.

They mock the idea of a rainbow nation, scoff at any suggestion they need white friends, and rightly ask why is there more wealth in the hands of the whites now than there was back then.

Mr Mandela is dead, a new black consciousness is alive and well. And it is angry.

After weeks of protest, the statue of British colonialist Cecil Rhodes was removed from campus

The loudest voices are of the students, who earlier this year began pulling down statues commemorating colonialism.

"Rhodes Must Fall," they said, and the University of Cape Town duly removed the statue of the British imperialist and mining magnate.

The born-free generation:

They are now demanding more black professors - still very much in a minority - and have been demonstrating about the proposed rise in tuition fees, storming parliament and converging in a mass demonstration outside the president's office.

And they want more than "I'm sorry" from the young generation of whites who so obviously, if unintentionally, have benefitted from apartheid.

But their voices are only being heard, their anger only being shared, because of what was achieved by Mr Mandela and his generation before they were born.

'Chocolate sprinklings'

They are the first generation of a new, educated, young, black middle-class, but they are still angry and that anger cannot be ignored.

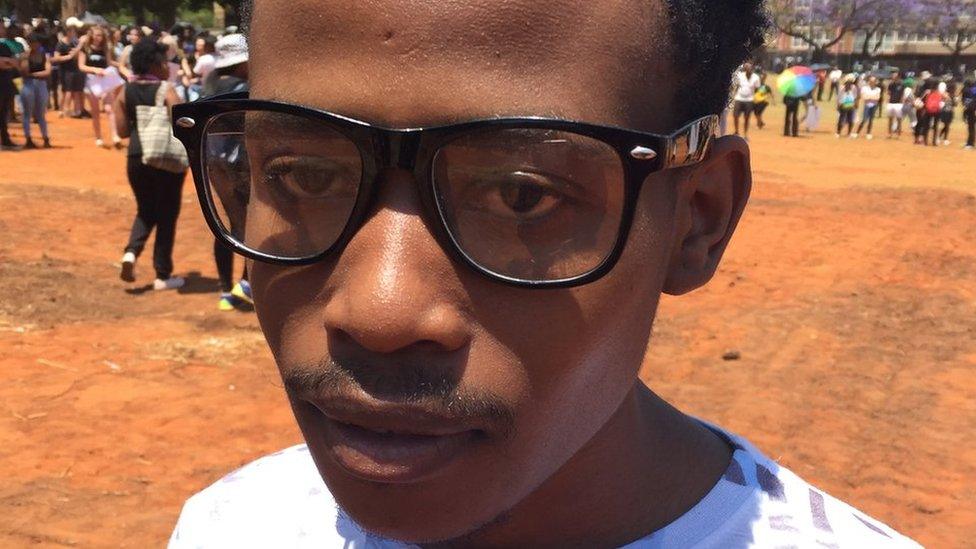

"South Africa is a cappuccino society," Panashe Chigumadzi said as we sat in a cafe in what was once a whites-only neighbourhood of Johannesburg.

Panashe Chigumadzi says young black people want the country's wealth to be spread more evenly

"A vast, huge, black majority at the bottom with a layer of white cream and a few chocolate sprinklings at the top of it," she says, referring to the small black elite who have gained great riches from the post-apartheid years - from a failed attempt to rebalance the wealth among the many.

"The 'add blacks and stir' model of society here hasn't worked," she tells me.

"There's a generational shift and a lot of young blacks are saying this is not enough."

There is maybe some unease or guilt in there - she is not one of the millions still living in the slums of sprawling townships, without clean water, with poor sanitation, and without a job, in what is among the most unequal societies in the world.

Naive?

Those people are angry too - they are doing what they can to demand change and as ever, loud, vocal street protest is one way to pressure a government increasingly seen as corrupt and out of touch with the needs of the people it once promised to help.

Fingers are being pointed at the party of liberation, the African National Congress (ANC), and the president whose extravagant home improvements were paid for by the state.

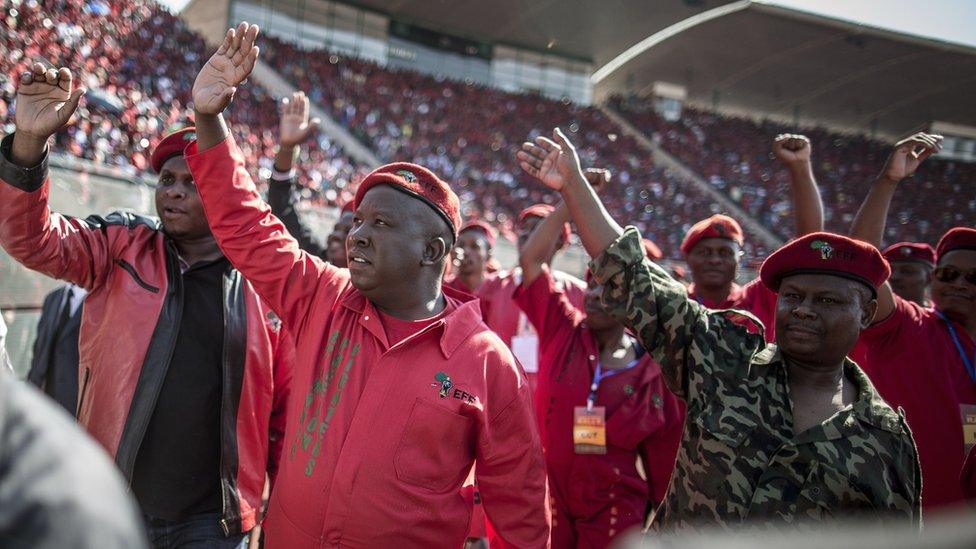

Radical leftists are drumming up support, reviving socialist ideas based on Venezuela or Cuba, looking to Russia and China, and basing their land reform proposals on Zimbabwe, ignoring its disastrous economy.

The government has also stalled - not quite sure which route to take as the economy stutters and the voices for more grow louder.

And, with their vast and conspicuous wealth, the finger is also firmly being pointed at white South Africans.

If it really is the end of the rainbow nation, that is indeed a concern - the end of that wonderful idea of forgiveness, the working towards peace and reconciliation; of all races and ethnicities coming together for the good of the country.

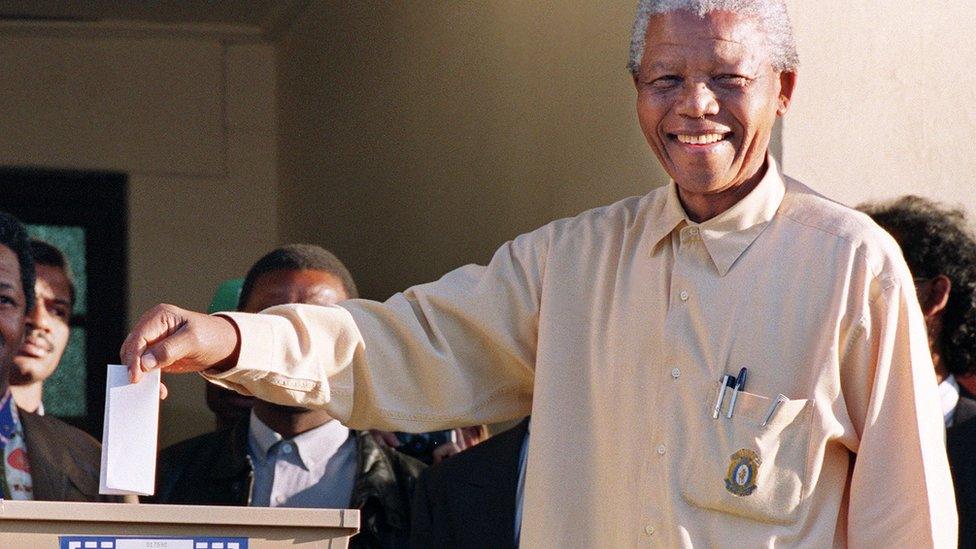

Nelson Mandela took part in the first democratic polls full of ideas of peace between races

The new Economic Freedom Fighters party focuses on rights for poor black South Africans

Perhaps it is the older generation, not the young, who are naive about that ideal.

Their biggest legacy is perhaps the constitution - the checks and the balances so smartly woven into the fabric of South Africa's democracy.

That freedom of speech - the independent bodies charged with holding government to account, and the brave people standing up for those ideals.

A white liberal journalist and commentator from the days of the struggle against apartheid, Max Du Preez, is not perhaps the person you'd go to for optimism, but he still believes in South Africa's future.

"We're facing a second transition in our society," he says.

"We had one in 1994 and now the game's up - we're having another one. But it's got to be peaceful. And it cannot destroy the economy."

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30. Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: At weekends - see World Service programme schedule or listen online.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published23 October 2015

- Published25 April 2014

- Published23 August 2012

- Published25 March 2015

- Published11 April 2015