Letter from Africa: Nigeria's disappearing storytellers

- Published

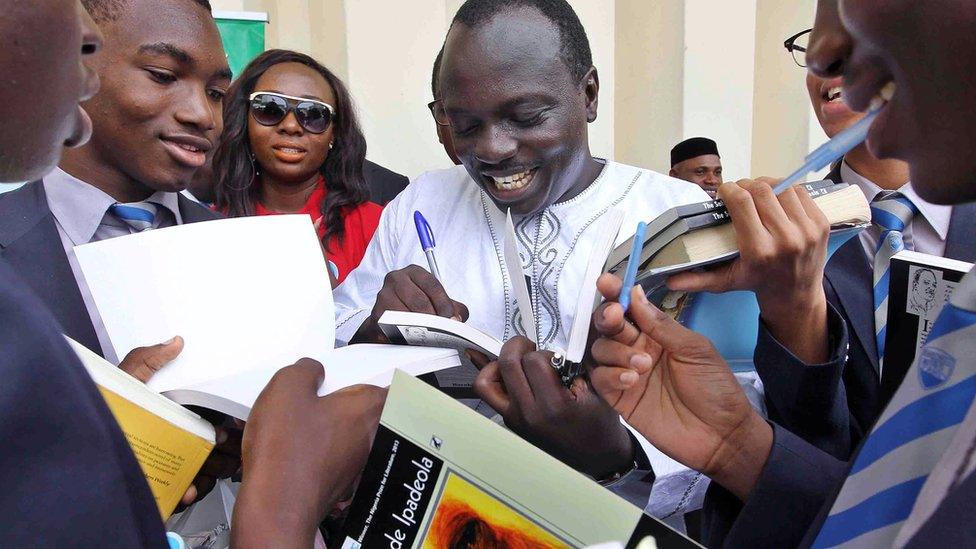

Poet Tade Ipadeola was awarded with the prestigious Nigeria Prize for Literature last year

In our series of letters from African journalists, Nigerian novelist and writer Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani considers if Nigerians are getting worse at writing good stories.

Last month, the judges of the $100,000 (£65,000) Nigeria Prize for Literature announced that there would be no winner for 2015.

Professor Ayo Banjo, chairman of the advisory board for the prize, declared that none of the 109 book entries met the required standard.

"Each book was found to manifest incompetence in the use of language," he said. Another judge described the entries as riddled with "grave errors".

Only books written in English are eligible for the prize. And, in Nigeria, quality of English is usually directly proportional to quality of education.

As the country's educational system has declined, the effect can be read and heard when Nigerians communicate in the tongue that was gifted us by our colonial rulers of yore.

Over the six years of Goodluck Jonathan's tenure as president of Nigeria, his wife Patience kept many middle-class Nigerians entertained by her customised version of the English language.

The Jonathans were Nigeria's first couple from 2010 until May this year

For example, she once extolled her husband's commitment to maternal health saying: "Goodluck said that... no woman will die again under pregnancy. He said that all Nigerian women, you have died enough."

And when she paid a hospital visit to some victims of a Boko Haram attack in Abuja, the former first lady expressed satisfaction that "the doctors and nurses are responding well to treatment".

But the laughter was usually accompanied by disdain.

Some described her as a disgrace to Nigeria and complained that someone who spoke such poor English had no right to represent our country on the world stage.

These critics were inadvertently calling for the majority of Nigerians to steer clear of the public stage. They were suggesting that millions of Nigerians keep their mouths shut.

Mother tongue v English

Often when I watch TV, listen to radio, read newspapers or interact with groups of people, locally, I arrive at the conclusion that, as far as grammar and pronunciation are concerned, many Nigerians have decided that Queen Elizabeth may go ahead and speak her version of English while they speak their own.

The mistakes and malapropisms may not be as amplified as Mrs Jonathan's, but they are nonetheless very much there.

Most Nigerians attend government-run schools, which these days have poorly paid and poorly trained teachers.

Most Nigerian children go to government-run schools

Mrs Jonathan herself was a qualified teacher, with a National Certificate in Education from the Rivers State College of Education to prove it.

The privileged Nigerians who attend privately owned schools learn better English, but usually pay heavy fees.

An option might have been for Mrs Jonathan to stick to her mother tongue, an interpreter constantly by her side.

But, in a country with such fragile ethnic fault lines, a national figure only engaging in her mother tongue could easily send the wrong message.

She may have been perceived as the first lady of a region rather than of the entire country.

Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani:

"If poverty in the country remains at the current dire level, fewer and fewer Nigerians will be able to afford to learn correct English"

Nigerian writers face a similar dilemma.

Undoubtedly, indigenous works form an essential part of a people's literary heritage. There is a place for them.

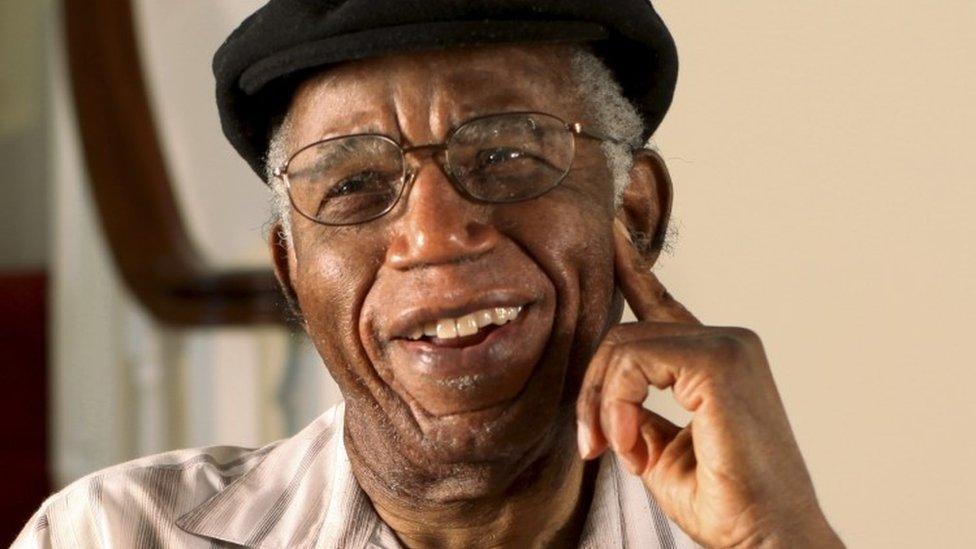

But, had Chinua Achebe or Wole Soyinka written in Igbo or Yoruba, they would probably not have been recognised beyond the boundaries of their ethnic groups.

These world-acclaimed writers may not even have been read widely among their own clans.

Not even the English are born with the ability to read their language. They are taught, usually in schools.

And the UN reports that more than one in three adults in sub-Saharan Africa are unable to read and write, while 47 million young people aged between 15 and 24 are illiterate.

Chinua Achebe's 1958 novel Things Fall Apart has sold millions worldwide

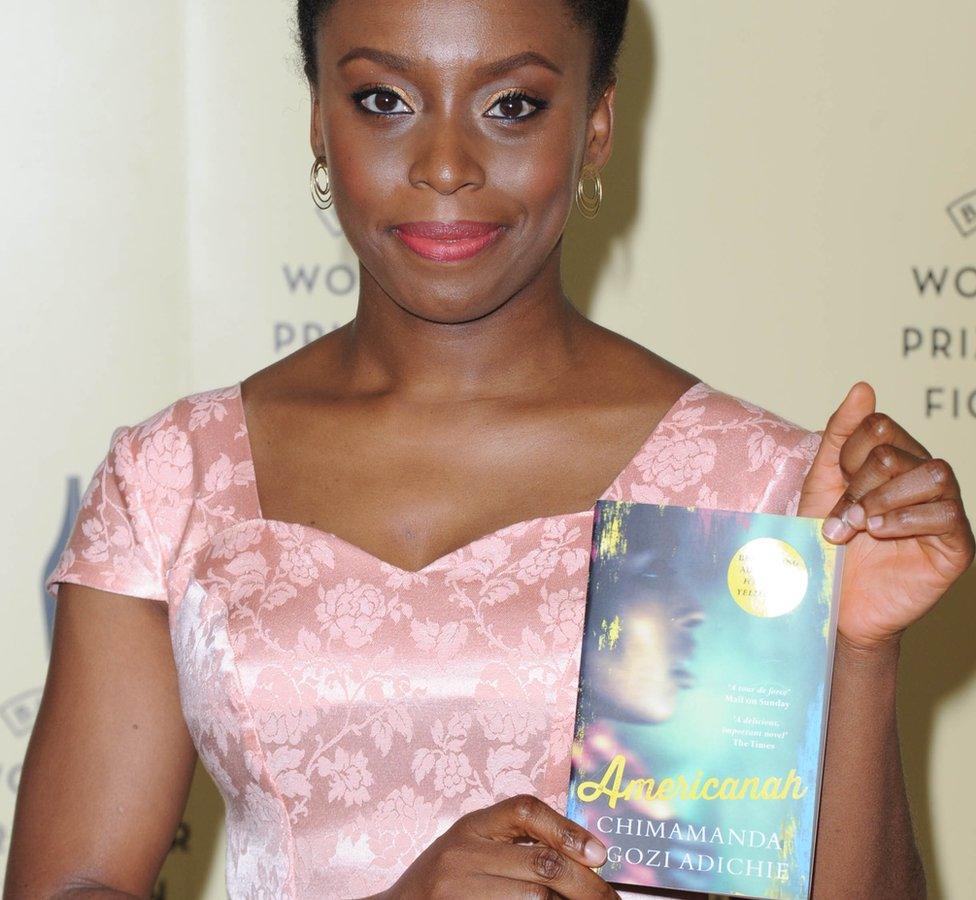

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is another award-winning Nigerian novelist who writes in English

In April 2015, no fewer than 10.5 million children in Nigeria were reported to be out of school, the highest number of any country in the world.

If poverty in the country remains at the current dire level, fewer and fewer Nigerians will be able to afford to learn correct English.

Fewer, no matter how skilfully they can tell a good story, will possess the competence in the use of the English language required by most literary prizes.

Consequently, many of Nigeria's greatest storytellers will continue to be denied a place on the literary stage.

And, sadly, their would-be page-turners will go with them to the grave.

More from Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani: