Burundi's tit-for-tat killings spread fear

- Published

Burundi's President Pierre Nkurunziza has given gunmen opposing his third term five days to surrender and be granted an amnesty or face tough anti-terrorism legislation to be introduced by the end of the month. It follows months of shootings in the capital, which the BBC's Alastair Leithead says has raised fears of a return to civil war:

I have been receiving the photographs for several weeks now. Every few days they pop up on my phone - usually with a little note: "These are the latest found today."

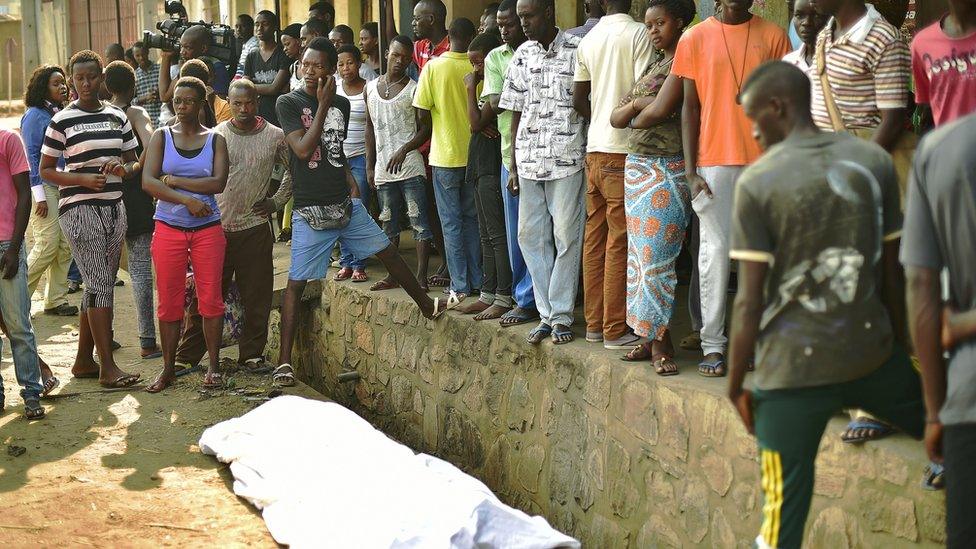

The person who is texting me is talking about bodies. Almost every day in Burundi a body is found, dumped in a storm drain or beside a road.

Alistair Leithead: "This is not an ethnic, Hutu-Tutsi conflict. But given this country's history, there's a real fear...that's what it could become"

Often they have been shot or stabbed in the chest; sometimes they have been tied up - usually somebody takes a picture.

The photographs and videos are posted on Facebook, or messaged from phone to phone - it is how people share information now.

The independent media is all but shut down. Many journalists and human rights activists have been scared out of the country.

One of the photos which appeared on my phone was of a well-known woman who had worked for the opposition party. The picture was delivered two days after she had gone missing.

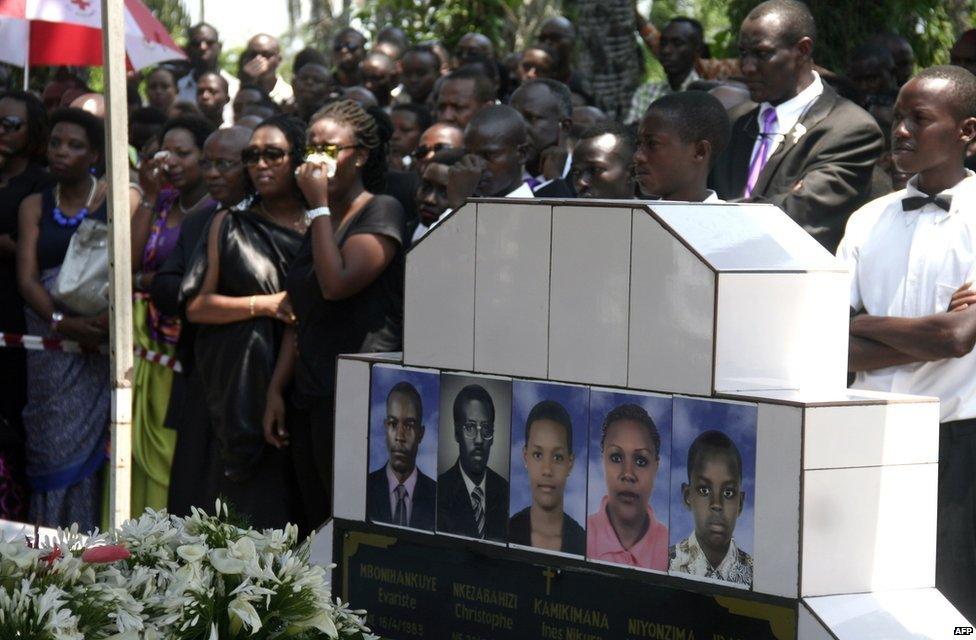

Journalist Christophe Nkezabahizi and his family were shot dead in the capital last month

Another was of Eloi Ndimira, a 54-year-old man who walked with a crutch and had tried to stop the police beating someone on the street. They turned on him.

The photograph is truly horrific. I will not even describe it.

We met his family as they were laying flowers on his grave; they were afraid to speak, to be seen with us.

Cleaning up his body for the burial, they found he had been beaten, stabbed, shot. And his heart had been cut from his chest.

Widespread terror

They were not the only two people to die in Burundi's capital, Bujumbura, in the last few weeks.

I recognised the neatly painted blue house number from the video clip: Number 48 Buye street.

Flies now buzzed at the foot of the red metal doors, where the video had shown a pool of blood-stained earth, marking the spot where Christophe Nkezabahizi had been shot twice, at close range, having done as the police asked, and opened the door.

Mr Nkezabahizi was a cameraman for the state broadcaster. He was not like the underground activists we met who know the risks of photographing the latest body to have appeared on the street.

He had not protested against the third term the president had gained after an election widely described as flawed. He had told the stories the government wanted telling.

The policemen knew this - he told them just before he was killed. They knew this when they told his family to lie face down in the street - just before they were all murdered.

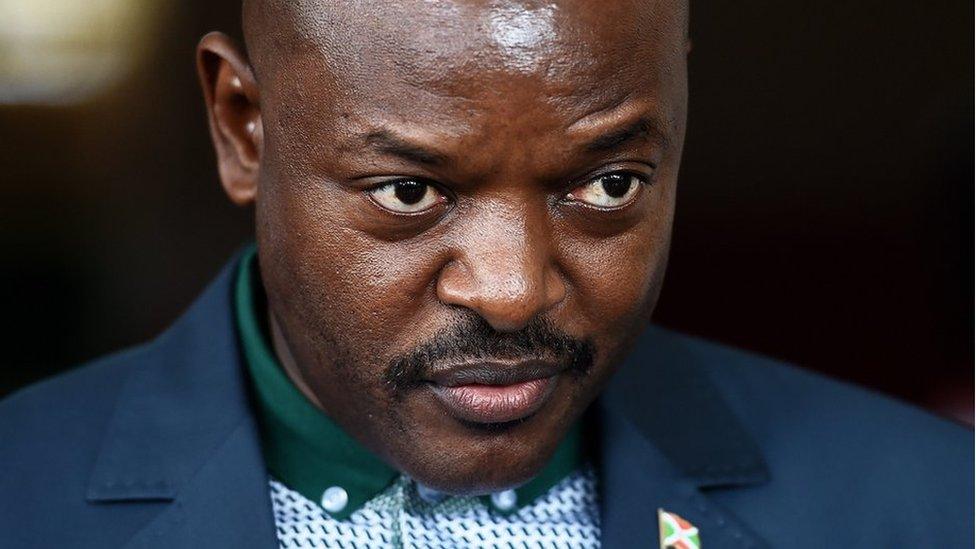

Who is President Pierre Nkurunziza?

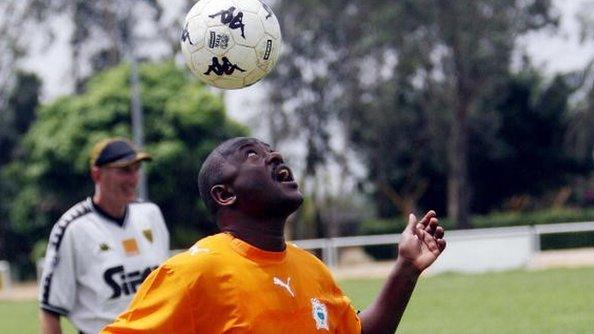

President Nkurunziza survived a coup attempt in May

A rebel leader-turned president, born in 1964

Born-again Christian who cycles and plays football

A former sports teacher

Married with five children

Father killed in ethnic violence in 1972

Burundi's Constitutional Court backed his argument that his first term in office did not count towards the two-term limit, as he was elected by MPs

Like its close neighbour Rwanda, Burundi has a dark past.

It was not called genocide here, but in the 1990s hundreds of thousands of people died in ethnic violence between Tutsis and Hutus.

This time the killing, so far at least, has not been based on ethnicity but is connected to Africa's new fever - third termism, where presidents are determined to have a third term in office whatever the constitution says.

It is sweeping the continent from Burkina Faso to the Congos, from Rwanda to Burundi.

But here, where ethnic divisions run so deep, there is a real fear - expressed openly on social media, or whispered in the close communities of the capital - of what could happen if this spiral of violence is not stopped.

Ethnic hate speech is starting to emerge from the shadows, the language of "us" and "them".

Terror is widespread, and that is probably the idea.

Politicians have been assassinated, perhaps the president's most powerful security figure was killed, and the country's best-known human rights campaigner barely survived after being shot in the face.

Murder is sometimes tit-for-tat, but also can be as random as it is brutal.

A man tells Alastair Leithead how he was tortured

People are picked up and tortured. I met one man - a truck driver - still in great pain after being arrested in June.

"His black week," he calls it. He was forced to sit in acid, to stand on nails, a jerrycan of sand was hung from his genitals.

He escaped when the cell door was accidentally left open. Too weak to walk, his last hope was to crawl out on his hands and knees.

He still does not know why he was picked on.

They accused him of weapons training; he says he is just a businessman from out of town.

Not all the killing is being done by shady police units aligned to the government.

Those who were protesting on the streets have been driven underground and now are responsible for their share of murder.

Grenades are thrown at patrol cars, police are kidnapped and killed.

It provokes a brutal response and the cycle continues.

Retaliation is why the police knocked at 48 Buye Street.

Mr Nkezabahizi did not kidnap or kill a policeman, but not knowing who did, the police picked on him and sent a strong warning to the community… those who act violently in Burundi, act with impunity.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30. Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: At weekends - see World Service programme schedule or listen online.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published2 November 2015

- Published13 May 2015

- Published14 October 2015

- Published18 August 2015

- Published21 July 2015