Can Pope tackle religious divide in Central African Republic?

- Published

Alastair Leithead visits the scene of recent religious violence

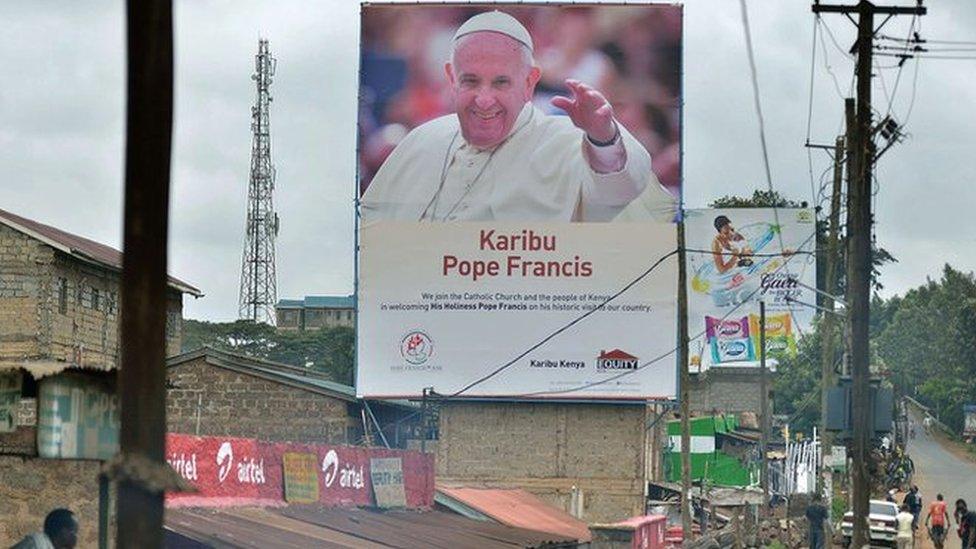

When Pope Francis put the Central African Republic on his itinerary, he gave his Vatican security officers a major challenge.

It's no longer full-blown civil war, but it's a country divided - on the surface at least - along religious grounds.

Every day gunfire and grenades ring out across the capital and countrywide, hundreds of thousands of people have been forced from their homes into enclaves that are either Christian or Muslim.

It's a risky place for a Pope to come, but of the three countries on his African adventure, the CAR has perhaps the most to gain from a symbolic visit.

For the past week, the Vatican police have been poring over the arrangements, checking out the venues he'll visit and making sure it's as safe as it can be for the pontiff.

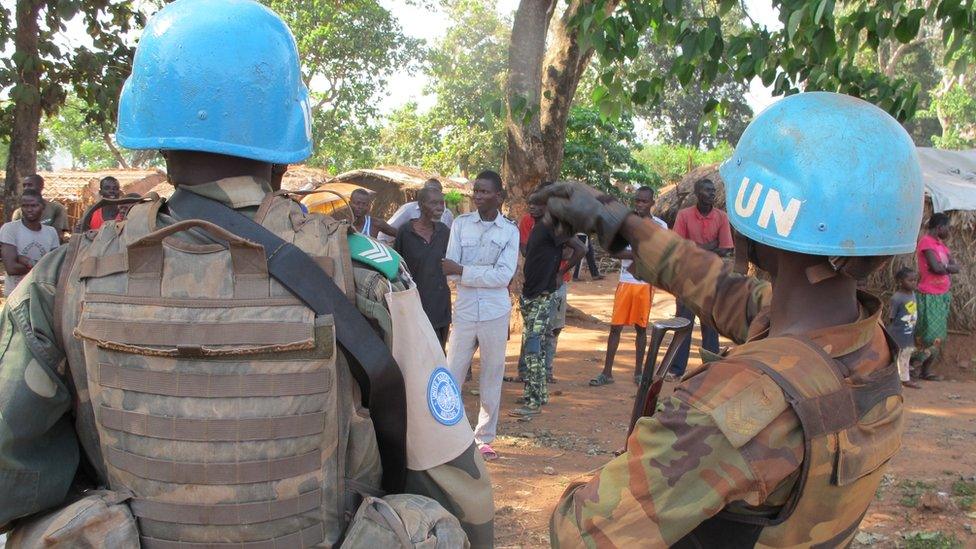

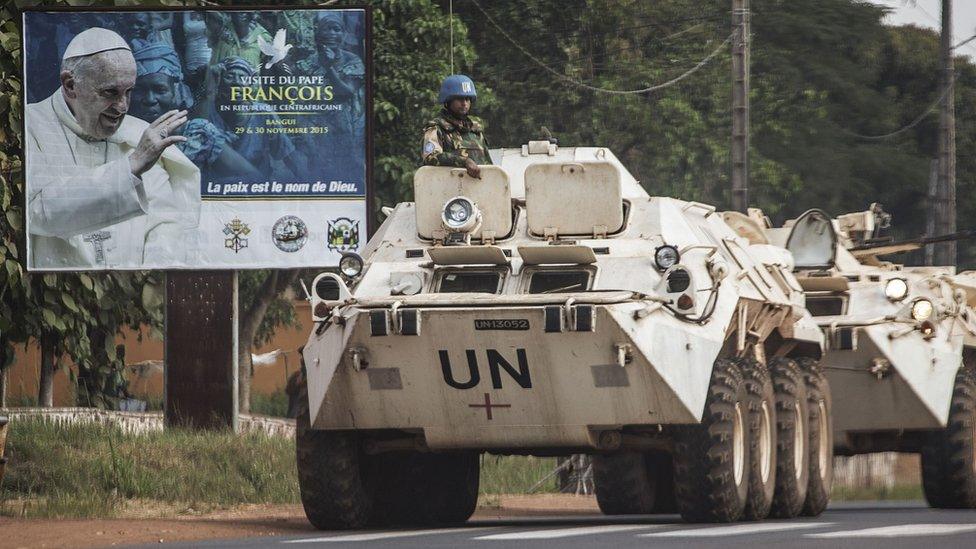

The UN has a peacekeeping force here, and French troops have an even heavier hand in trying to impose peace, complete with tanks and armoured cars, rumbling around the capital.

Pope Francis is set to visit the Central African Republic (CAR), which has been hit by Christian-Muslim conflict

Hundreds have sought refugee near Bangui's main airport

Security was ramped up ahead of the Pope's visit

"We are quite comfortable," said General Bala Keita, acting force commander of the UN mission.

"We will never ensure we can secure the Pope 100%, but I think the level of security we have put on the ground is acceptable for the Pope to come and visit without a lot of hitches."

If the aim is to bring all sides together, Pope Francis has achieved that simply through the planning process.

'Dangerous division'

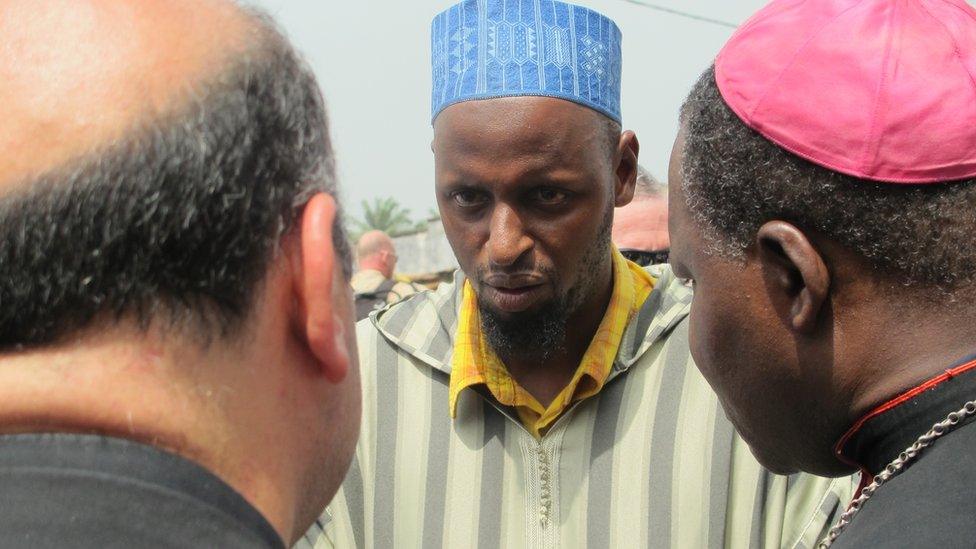

At the Grand Mosque in the notoriously dangerous PK5 neighbourhood, a large group of Vatican police, all wearing pale blue polo shirts, talked with the Bishop, the Imam and the Papal Nuncio, or Pope's ambassador to the CAR.

The religious leaders don't need convincing - they all have the same message - this is not a religious conflict, but about power and politics which have created a false but very dangerous division.

That doesn't stop the attacks, and nor did it prevent a gun battle from breaking out just outside the mosque as discussions about the Pope's security arrangements were coming to a close.

It was perhaps the deciding factor over whether he will need an armoured car for his visit to Bangui.

The Papal Nuncio and Archbishop met the Imam in Bangui

Some said Bangui was too dangerous for the Pope to visit

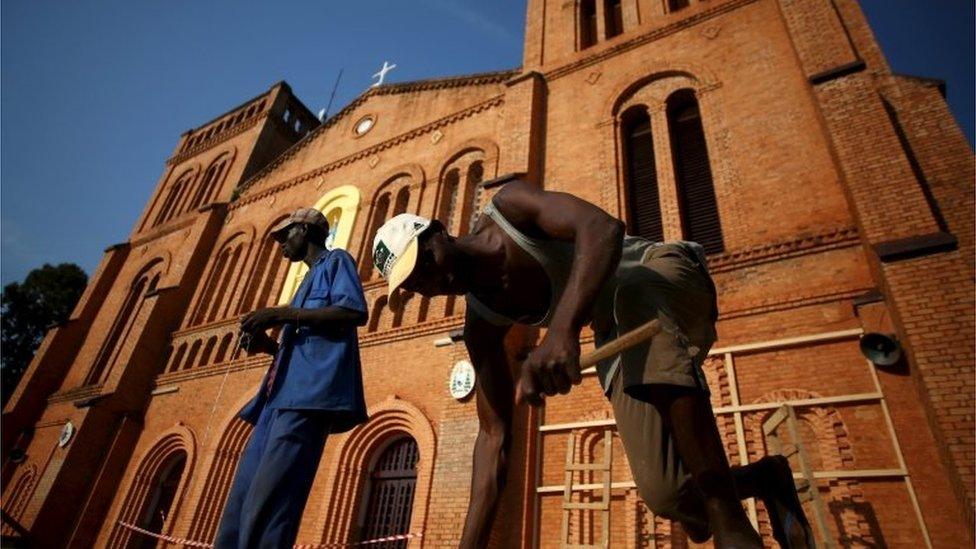

Workers have been busy outside Bangui's cathedral

At the cathedral, wooden platforms were being hastily built outside, the wooden roof was being repainted by a man balanced on precarious scaffolding, and the priest was walking the clergy through the service, step by step.

"The Pope said he wanted to come here as he was very worried about the situation," said Archbishop Franco Coppola, the Nuncio in Bangui.

"He wanted to come in the first place to comfort those who have been in any way wounded or affected by the war and to encourage the efforts on the road towards peace and reconciliation."

Central African Republic:

Population: 4.6 million - 50% Christian, 15% Muslim, 35% Indigenous beliefs

Years of conflict and misgovernance

Conflict only recently along religious lines

Previously ruled by Emperor Jean-Bedel Bokassa

Rich in diamonds

10,000-strong UN force took over a peacekeeping mission in September 2014

France has about 2,000 troops in its ex-colony, first deployed in December 2013

War has blighted the CAR for decades, but it was only three years ago the fighting took on a religious form.

A group of mostly Muslim rebels from the north called the Seleka marched on the capital, briefly taking control of the country.

Their rebellion tapped into a feeling northerners had of being excluded and unrepresented by the central government.

But the choice of target, as they fought their way to power, was churches and Christian communities.

It wasn't long before the targets of their anger mobilised and retaliated.

The anti-Balaka - ironically meaning anti-violence - hit back, and so began a downward spiral of tit-for-tat violence which continues today.

Towns and villages are divided, with hundreds of thousands of people displaced into camps divided along religious grounds.

Bishop Dennis Kofi Agbenyadzi, from Berberati, sheltered thousands of Muslims in his church when they were attacked

A teacher at a Christian camp in the second city of Bambari - which had been attacked just days before - said if the children crossed an invisible line to get to school they'd be "chopped into pieces", making a cutting action with her hand.

Three people were killed and dozens were injured after an attack burned 30 huts to the ground.

The Central African Republic is rich in minerals - the motivation to violence is more about control of the gold and the diamond mines.

"They just use a religious umbrella," the Bishop of Berbarati, Dennis Kofi Agbenyadzi, told me in the church grounds where he had given shelter to Muslims when the cycle of killing came to his door.

"Religion arouses emotions, not reason," he said. "It's being manipulated."

That's perhaps why the Pope wanted so desperately to come to the CAR - to draw attention to the futility of the division and to try and bring communities together against the violence.

- Published25 November 2015

- Published26 November 2015

- Published26 November 2015