Bomb shakes Tunisia's fragile democracy

- Published

A suicide bomber struck in Tunis

Tunis was rocked last month by a suicide bomber, external who targeted a bus that transports the presidential guard - 12 people died and another 20 were injured.

So-called Islamic State (IS) claimed responsibility for the attack.

This was the third major deadly attack in the country this year and the first bombing of its kind in the heart of the capital.

It was a significant development - a symbolic attack against the liberalisation of the state in recent years, and a challenge that will test this fragile democracy.

Hours after the bus bombing, and metres away from the interior ministry hospital that was treating the wounded of the presidential guard, a man walked into a shop and shouted the name of the deposed president: "Ben Ali, Ben Ali!"

A friend had been rushing to make a quick purchase before the 21:00 curfew came into effect.

After recounting what he witnessed, he concluded: "It's very telling."

This region was transformed in the aftermath of the so-called Arab Spring, triggered by the overthrow of President Ben Ali in 2011. An autocratic regime was replaced by a democratic one with progressive ambitions, underpinned by a new constitution enshrining freedom of religion and women's rights.

However, stifling policies akin to a police state, external and reminiscent of the Ben Ali years, have since been adopted to counter the threat of extremism, graphically illustrated by the attack on the beach resort of Sousse earlier this year, which left 38 people dead.

There is a danger the country could slip back into its "old ways", and that the current rulers will lose sight of how to respect civil rights in the name of security.

In the aftermath of the latest bombing, the president imposed a nightly curfew, announced a 15-day closure of Tunisia's border with Libya - where it is believed militants are trained - and reinstated a 30-day state of emergency.

In a news conference the next day, the Prime Minister, Habib Essid, said fighting terrorism was not solely the responsibility of the state, but of the whole nation.

He said Tunisians had to protect their way of life because "those people coming from abroad would like to change that".

Home-grown militants

This might have sounded reasonable but all the major attacks that have blighted Tunisia this year have been carried out by locals.

The suicide bomber, according to officials, was Houssem Abdelli, a street vendor who lived in Doaur Hicher, a town just 15km from the capital.

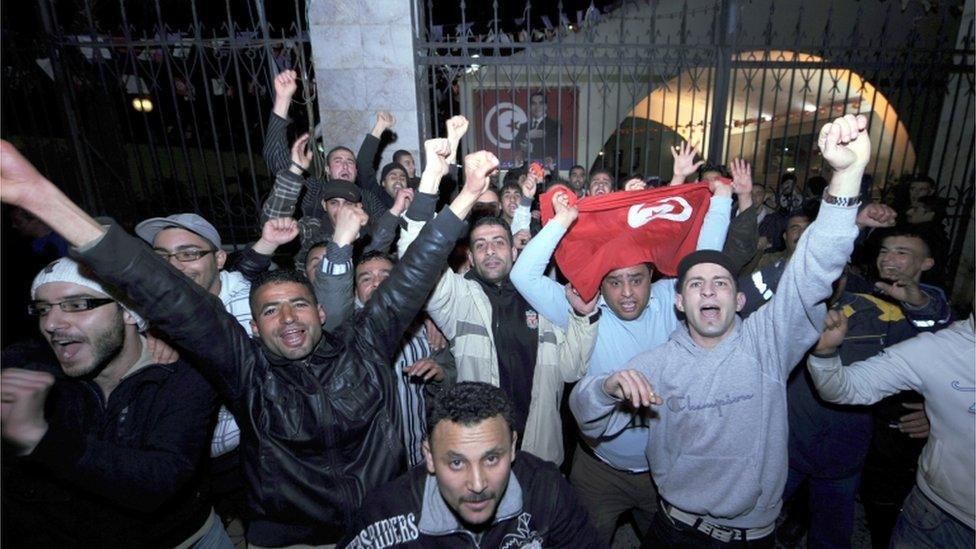

The toppling of President Ben Ali was met with an initial surge of optimism in Tunisia

It is poor and linked with everything from ultra-conservative Salafism to a thriving black market in drugs and alcohol.

In 2012, clashes between the police and Salafists there killed two.

Tunisia is still the country that exports the highest number of jihadists in the region.

Active militant groups in the country include Okba Bin Nafaa and Jund al-Khalifah - an IS affiliate.

In November, Jund al-Khalifah claimed responsibility for the beheading of a 16-year-old shepherd in Sidi Bou Zid, accusing him of spying for the authorities.

Knee-jerk reactions to deadly attacks may be understandable: most Tunisians want to protect the freedoms they have gained in recent years. Increasingly you hear people speak of the need for the government to "wipe out all the Islamists".

But shutting down mosques and borders, policing social media accounts, house raids and house arrests offer few long-term results. And some foreign diplomats would question the merits of a new plan to recruit 6,000 new police and soldiers.

Tunisia needs a fresh approach to problems, such as poverty, that previous dictatorships buried for decades.

The government is not completely oblivious to this; officials plan to kick-start a youth employment programme in 25 regions.

Politically mature

But politicians are bickering. In the past month, the ruling party, Nidaa Tounes, appeared on the verge of collapse, with 31 MPs threatening to resign, on and off, from the party's parliamentary bloc.

Tunisian Nidaa Tounes party members held a vigil for the victims of the suicide attack

If they do go through with it, it would give the moderate Islamist party Ennahda a majority presence in parliament.

The immediate, and perhaps premature, assumption is that such a move would destabilise the country, threaten the existence of the coalition government and chaos would ensue.

But although Tunisia is a young democracy, it is politically mature, with a highly educated population and has a solid foundation of civil society establishments to fall back on.

These realities, and the US and UK's increased involvement in counter-terrorism aid and training, are likely to shield the state from the chaos seen elsewhere in the region - notably in Libya.

But Libya's unstable, lawless existence - with a free-for-all weapons bazaar - and the rise of IS are not helping its neighbour. And, of course, violence is not confined to this so-called troubled region.

Tunisia needs to face its own demons. The quicker politicians identify what's driving the radicalisation of its youth, and how to prevent it and contain it, the better.

Ousted President Zine el Abidine Ben Ali

Tunisian Revolution:

Protests sparked by the self-immolation of street trader Mohamed Bouazizi on 17 December 2010

Demonstrations - calling for political freedoms and action to address poor living conditions, high unemployment, food inflation and corruption - spread, resulting in many deaths and injuries.

President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali officially resigns on 14 January after fleeing to Saudi Arabia, ending 23 years in power

The Constitutional Court affirms Fouad Mebazaa as acting president. A caretaker coalition government is also created, including members of Ben Ali's party, the Constitutional Democratic Rally (CDR) along with opposition figures.

Street protests continue in Tunis and other towns, demanding the disbanding of the CDR.

On 27 January Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi reshuffles the government, removing all former CDR members other than himself.

On 6 February the new interior minister suspends all party activities of the CDR, and the party is dissolved a month later.

Elections are announced in March for the Constituent Assembly. On 23 October 2011 the Islamist Ennahda Party wins most seats.

Nidaa Tounes - a big-tent secularist party - subsequently took power following elections in 2014.

- Published25 November 2015

- Published2 July 2015

- Published30 October 2014