Has holy city become jihadist breeding ground?

- Published

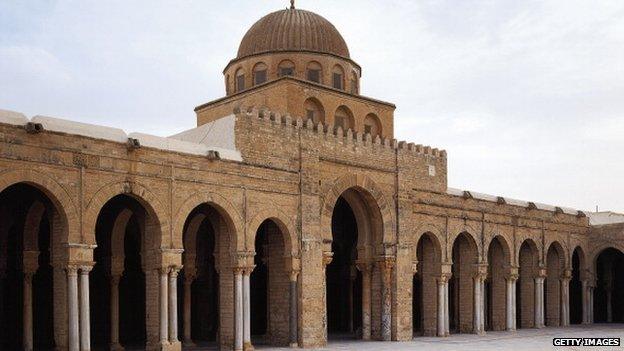

The Great Mosque is hailed as an architectural masterpiece

When the so-called Islamic State (IS) claimed responsibility for last week's attack at the beach resort of Sousse in Tunisia, it celebrated the gunman, Seifddine Rezgui, by his nom de guerre, Abu Yahya al-Qayrawani.

As often, his given surname was a reference to where he came from; or rather, in this case, where he was studying, the city of Kairouan.

It has since emerged that Seifddine Rezgui had completed the first year of his masters degree only two weeks before he carried out a massacre of at least 38 people.

Teachers and officials of Kairouan's Institute of Applied Science and Technology are adamant: Rezgui was a "normal student" throughout the four years that he spent there.

Was it Kairouan that turned the 23-year-old into a "soldier of the caliphate"?

The ancient city, located in the centre of Tunisia at an almost equal distance from the sea and the mountains, is one of the oldest Islamic centres in the world.

Over the past few days, residents have been keen to tell journalists that it is not a place of "terrorists."

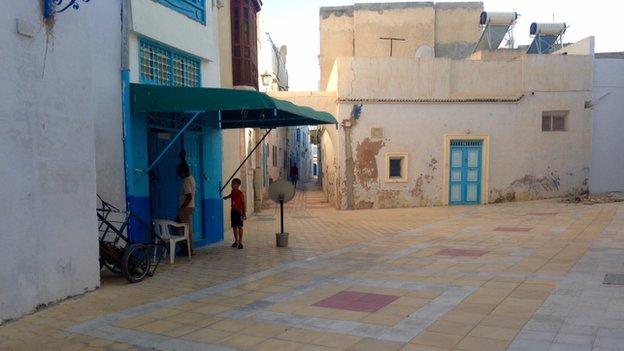

Until recently, tourists would flock into Kairouan's narrow and windy streets surrounded by ramparts to visit its remarkable monuments.

Rich heritage

A World Heritage Site, it is home to the Mosque of the Three Doors, the oldest known mosque with a sculpted facade.

At the heart of the old part of town, the Great Mosque, with its marble columns, is described by Unesco as "an architectural masterpiece that served as a model for several other Maghreban mosques".

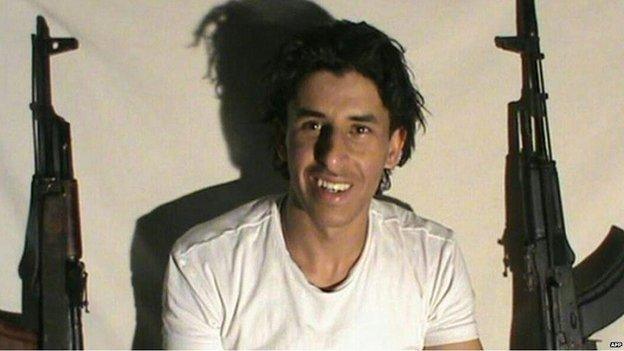

This image of the clean-shaven Seifeddine Rezqui was distributed by IS-linked social media accounts

Kairouan was founded in 670 and remained the capital of the Muslim world in North Africa for four centuries.

Tunis was then chosen as the political capital in the 12th Century, but Kairouan remained the main holy city in the Maghreb.

"The city was largely marginalised under [former President Zine El Abidine] Ben Ali, and Islamist extremists took control of Kairouan after the 2011 revolution," says Alaya Allani, an analyst of terror groups.

In the two years following the overthrow of Ben Ali, Salafist Islamic fundamentalists and radicals took control of dozens of mosques in the city and gained ground through charity and humanitarian actions.

As in many other towns in Tunisia, preaching tents were erected on a weekly basis in front of schools and supermarkets to attract followers.

This is how the extremist group Ansar al-Sharia rapidly grew, undisturbed by the new Islamist administration.

Its members want to re-create the ancient North African caliphate, and reinstate Kairouan as the capital.

But the town was not a jihadist stronghold, according to Mr Allani.

"It was more a place for radical theoretical work rather than jihadism," he says.

Jihadist fighters would rather emerge from the towns of Bizerte, Djendouba, Kasserine or Sidi Bouzid.

"But they have created sleeping cells in Kairouan, and these are still active," Mr Allani says.

In 2013, Ansar al-Sharia was labelled a terrorist group and the government clamped down on the organisation, neutralising most of its domestic capacity.

While many have been arrested, hundreds of members - from around the country - are believed to have travelled to Syria and Iraq to fight within the ranks of IS.

Fedi Saidi, head of the General Student Union of Tunisia's Kairouan branch, told BBC News at least 25 students had travelled to Syria to fight.

Kairouan was the main holy city in the Maghreb

He added he had warned the city's authorities last month that an attack could be imminent, giving them the details of the students who had travelled to Syria.

But Abdelwaheb Alouini, from the Kairouan police, said: "We hear some warnings every day.

"Sometimes they're correct, but sometimes they're not.

"You can't imagine the effort we make every day to protect our country from terrorism."

If Seifddine Rezgui was being groomed to commit a massacre, he never showed signs of extremism.

He did not even grow a beard or change his clothing style.

"It is quite possible that he was being seduced by radical views over the internet and Kairouan simply provided the right environment for them to grow in his head," Mr Allani says.

Like many youths, Nada Mrabet decided to adopt that ideology after the revolution.

"It was out of desperation. I was under a lot of pressure, and sometimes you feel like you need to cooperate with the community you live in," she told the BBC.

"So we tried to embrace the way they think, so that we wouldn't get into too much trouble.

"Now, I have decided to change and be independent.

"You can have a lot of enemies just for saying what you think."

Kairouan has inspired another extremist group, known as Okba Ibn Nafaa and linked to al-Qaeda.

In fact, its name is that of the city's founder, who also commissioned the building of the Great Mosque.

In the attack on the Bardo Museum, 22 people died

Security officials allege Okba Ibn Nafaa was behind the attack on the Bardo museum in Tunis in March, in which 21 tourists and a Tunisian were killed.

"It is probably the most dangerous group in Tunisia right now," says Mr Allani.

"Its members - most of whom are Algerian - have spent much time in training abroad, they are a lot more experienced."

History and culture are very much palpable in Kairouan, with its medina, surrounded by 3km (two miles) of walls, and a skyline punctuated by the minarets and domes of its mosques and monuments.

Extremists have been trying to claim it back, but along the winding streets, residents who have sighted foreigners give us a gentle: "Welcome."

"Please don't speak badly of our town," one man said.

"There are no terrorists here, we are good people."

Tunisia beach attack: The victims

The names of those killed in the attack are being released. Here's what we know so far about those who lost their lives, as well as those who are injured and missing.

Some survivors have also been speaking out about their ordeal.

Special report on the Tunisia attack

Profile of gunman Seifeddine Rezgui