Letter from Africa: Why rat poison is big business in Nigeria

- Published

In our series of letters from African journalists, novelist and writer Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani looks at Nigeria's current war on rats.

A recent headline in a local newspaper captured the reaction of many Nigerians to the latest disease outbreak in our country: "From Bats To Rats As Lassa Fever Takes Off Where Ebola Stopped".

Rats are the newest terrorists in town.

Since August 2015, the Lassa haemorrhagic fever outbreak, which is usually transmitted via infected rats, has spread to 17 states in Nigeria, resulting in about 76 fatalities, including at least one doctor who had treated infected patients.

However, Nigeria seems bent on ensuring that rats do not do as much damage as the bats, who were the primary carriers of Ebola, which left more than 11,000 dead after it began in Guinea in 2014 and spread to 10 other countries, including Nigeria.

We may not have a Pied Piper to lure the pests into the River Benue with his shrill notes, but the federal government has appointed a National Lassa Fever Action Committee to plan how to halt the outbreak.

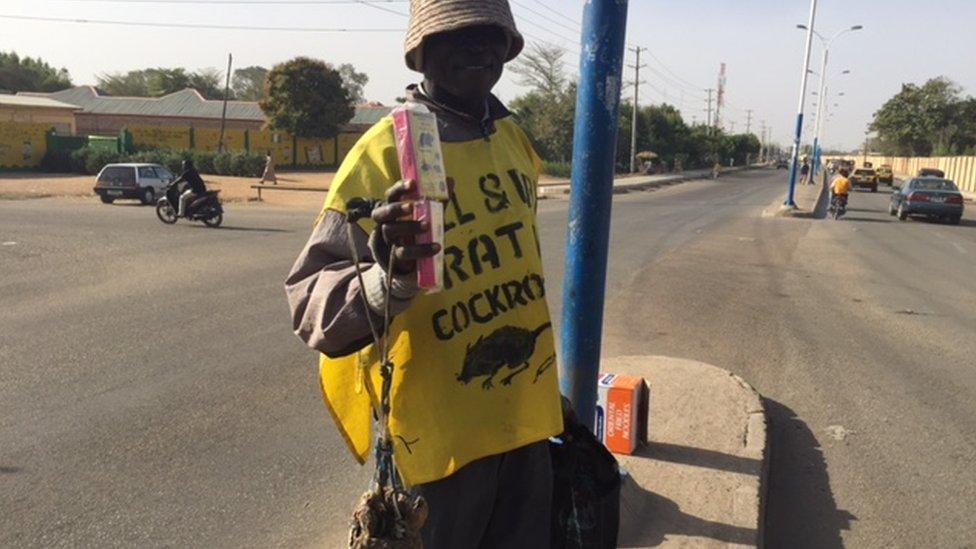

Rat poison seller:

"The Boko Haram Rat Disposal was an instant hit, becoming very popular with customers"

"With the resources available to us, we will collectively eliminate the disease in Nigeria soon," assured the Minister of Health, Isaac Adewole, at a meeting during which the committee was inaugurated.

Meanwhile, a ban has been placed on eating rats - a delicacy in certain parts of the country - which my friend's father tells me tastes like grasscutter or squirrel meat.

"You remove the entrails and roast it without boiling it first," he said.

"When you add some pepper and salt, it becomes quite tasty."

As a young man in the late 1960s, he had fought on the Biafran side during the civil war, when many ethnic Igbos were forced to eat rodents in order to ward off starvation.

In addition, public service announcements continue to warn against consuming foods that may have been exposed to rats, especially when not prepared with heat.

Particular caution has been drawn to the drinking of garri, a powder produced from cassava that is sometimes left open in storerooms accessible to rats.

Garri soaked in water, with sugar or salt, is considered the most affordable meal in Nigeria, often described as "poor man's food".

Lassa fever

The virus is transmitted to humans from rodents that harbour the virus

Endemic in parts of West Africa

The multimmate rat is the carrier

Usually transmitted to humans via contact with food or household items contaminated by its urine or faeces

Symptoms of the viral haemorrhagic illness: Fever, headache, sore throat, cough, nausea, diarrhoea, muscle pain

Person-to-person infections can occur through contact with bodily fluids

100,000 to 300,000 infections every year with about 5,000 deaths

Deafness occurs in 25% of patients who survive the disease

Source: World Health Organization/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Then, of course, there are the ubiquitous sellers of rat poison, young men who appear out of nowhere in traffic and push their wares against the window of your car, a string of mummified rats dangling in their other hand.

With the rise of the Boko Haram insurgency a few years ago, some of these pedlars no longer need a collection of dead rats to help us visualise the destruction their wares can accomplish.

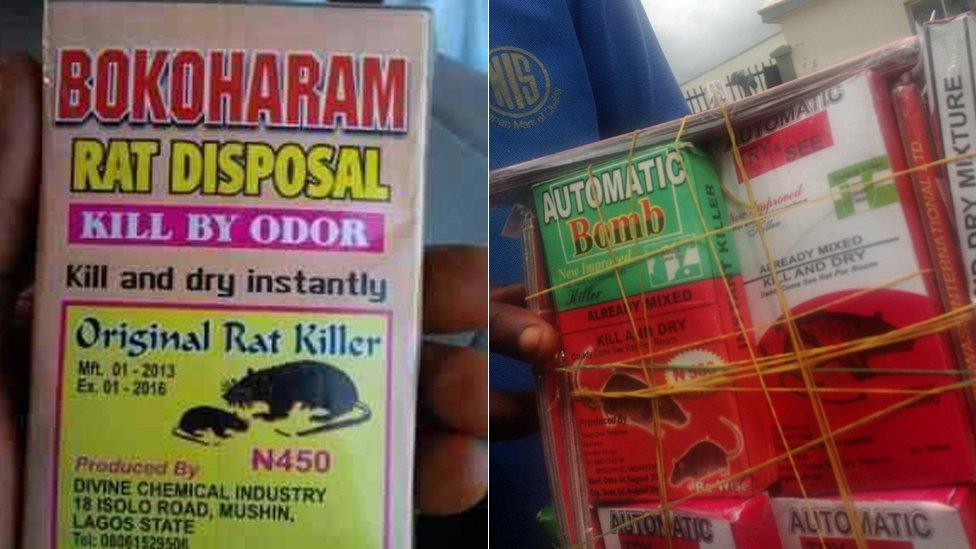

They allow new brand names to do the job, such as "Automatic Bomb Rat Killer".

Evocative name

The owner of Divine Chemicals, which produces "Boko Haram Rat Disposal" was happy to tell me the motivation behind his choice of rat poison name, although he declined to have his name published.

"The way they kill people is the way the rats need to be destroyed," he said, referencing images from the aftermath of Islamist militant bombings.

Many towns in the north-east have been destroyed during the Boko Haram insurgency

Divine Chemicals was already in the business of rat poison before the insurgency began, but decided on the more evocative name after two of his relatives were killed in separate bomb attacks in northern Nigeria.

The "Boko Haram Rat Disposal" was an instant hit, he told me, becoming very popular with customers. "The thing is moving market," he said.

Not long after my initial conversation with Divine Chemicals, which took place over a year ago, he dumped the lucrative name.

His loved ones were worried that it might attract the attention of the wrong people, he explained - that the rightful owners of the Boko Haram brand might take offence.

Strangers also rang occasionally to caution him against his choice of name, good Samaritans worried about the possible dire consequences.

With the current Lassa fever outbreak, I imagine that Divine Chemicals will once again begin to see a boom in sales, despite having jettisoned its lucrative product name.

Hopefully, with this widespread war on rats, the minister of health's bold prediction will prove accurate - and, like Ebola in Nigeria, this Lassa fever too shall soon pass.

More from Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani: