Is South Africa's education system really 'in crisis'?

- Published

South Africa's Education Minister Angie Motshekga says parents should do more to help their children

South Africa's minister of education openly admits that the country's schools are in a state of crisis. How did we get here and what needs to be done?

Angie Motshekga did not mince her words when she addressed her colleagues at a recent African National Congress (ANC) gathering.

"If 25% [of students] fail, we must have sleepless nights," she is quoted in local media as saying, external.

"This is akin to a national crisis."

Not about the money

The shocking statistic is that some 213,000 children failed their end of school examination for the academic year ending last month, out of a total of nearly 800,000.

But that is just half the story, as there is also a massive drop-out rate.

According to Stellenbosch University's Professor Servaas van der Berg, out of the 1.2 million seven-year-olds who enrolled in Grade 1 in 2002, slightly less than half went on to pass their school-leaving exam, the matric, 11 years later.

This is not about a lack of funding. In fact, South Africa spends more on education, some 6% of GDP, than any other African country.

There are an estimated 12 million children in school in South Africa

But quality education for everyone is not there, as in many global studies South Africa often comes near the bottom in maths and science tests.

The cancer lies deep in the education system and the continuing legacy of apartheid, and parents know this.

'Packed like sardines'

One of the most depressing sights in post-apartheid South Africa is the bussing of black children out of townships like Johannesburg's Soweto.

Children are packed like sardines into mini-buses and driven long distances, some over 30km (19 miles) away, to the schools in the former whites-only suburbs.

Some will be travelling to private schools, but the majority go to the state-funded schools which are better resourced and have better teachers than their equivalents in the townships, mirroring the situation during apartheid.

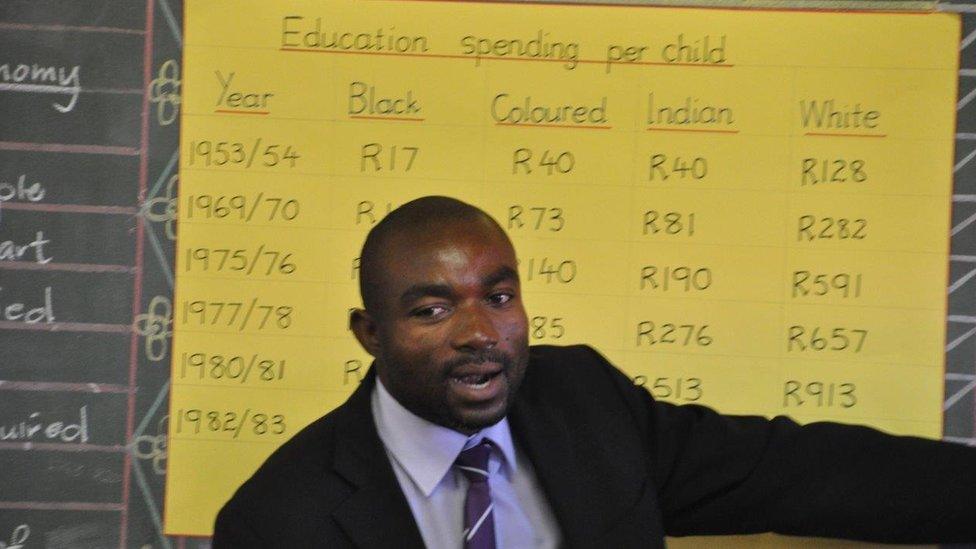

The apartheid government invested much less in black education than white schools

At that time, the white minority government spent four times more on a white child's education than it did on a black child. This disparity is no longer the case, but the legacy is still there.

Leader of the opposition Democratic Alliance Mmusi Maimane explained the legacy of that system recently when he spoke about the scourge of racism.

"We are entitled to ask why a black child is 100 times more likely than a white child to grow up in poverty," he said.

"We are entitled to ask why a white learner is six times more likely to get into university than a black learner."

Rather than disagree, the education minister chimes in.

"Twenty years down the line we still have the legacy of apartheid," Ms Motshekga told the BBC, "we still have teachers who were not trained for the future".

Poor teaching

There are many schools in the townships and the government has built more schools in these areas since the advent of democracy, but quality teaching and a proper structured learning process is lacking.

The most tragic anecdote of how serious the problem is comes from a World Bank study conducted in rural Limpopo province back in 2010.

The study asked 400 12-year-old students to work out the answer for 7 x 17.

To work it out, the pupils first drew 17 sticks and counted them seven times. Some 130 of the 400 got the right answer.

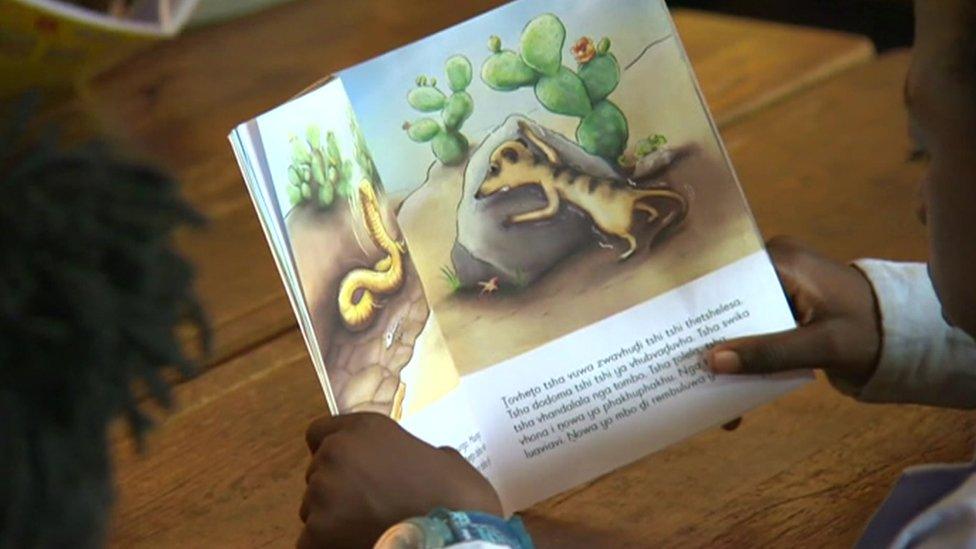

Students can be at a disadvantage depending on what language they are taught in

But when the same question was presented in word form in English, things spiralled downwards.

Researchers asked the students: "If there are seven rows of 17 chairs how many chairs are there?" None of the children answered correctly.

So language and the quality of teachers are huge areas of concern.

There are 11 official languages in South Africa but most teaching is in English, especially for subjects such as maths and science.

Professor John Volmink, chairman of the education quality assurance body Umalusi, has studied the relationship between the language of instruction and how students perform.

"It remains true that candidates writing the examination in a language other than their home language continue to experience great difficulty in interpreting questions and phrasing their responses," he is quoted in the the City Press newspaper as saying.

"Teachers' knowledge of English has to be upgraded. Unless we [support them], results will continue to drop."

Pupils can miss out on a lot of learning if teachers are not turning up for work

All that aside, the education minister is also taking on the unions, who are seen to be part of the problem by appearing unwilling to tackle absenteeism.

Some teachers are not turning up to work for parts of the week, which means that students over time can lose out on months, if not years, of learning.

But Ms Motshekga told the BBC that she wants to take the politics out of education.

"I fight a lot with unions behind closed doors, I don't call the media to make a show of it," she said.

"I do it responsibly in a manner that corrects the wrong but keeps the system together."

'There is hope'

But with all of the above, it is not all doom and gloom.

South Africa's education minister wants everyone to work together to improve education

There are schools which continue to produce good grades under some of the most difficult circumstances.

In Sibasa, Limpopo province, where students regularly struggle without some of the most basic equipment, Mbilwi Secondary School achieved a 100% pass rate for the school leaving exam.

And there are many private schools that are producing well-educated students every year.

As Mr Van der Berg aptly put it: "We don't want people who made it in spite of the system."

- Published28 December 2015

- Published13 November 2015

- Published3 October 2012

- Published12 March 2012