Letter from Africa: Judiciary on trial

- Published

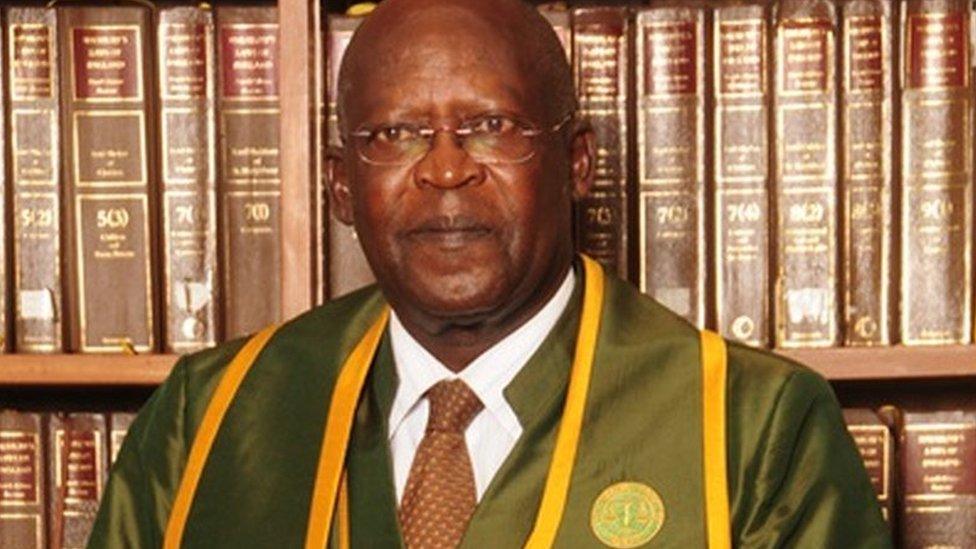

Judge Philip Tunoi will now be investigated over whether he took a bribe, which he denies

In our series of letters from Africa, journalist Joseph Warungu reflects on the rocky times that the judiciary has been facing in two countries in East Africa.

"Why hire a lawyer when you can buy the judge?"

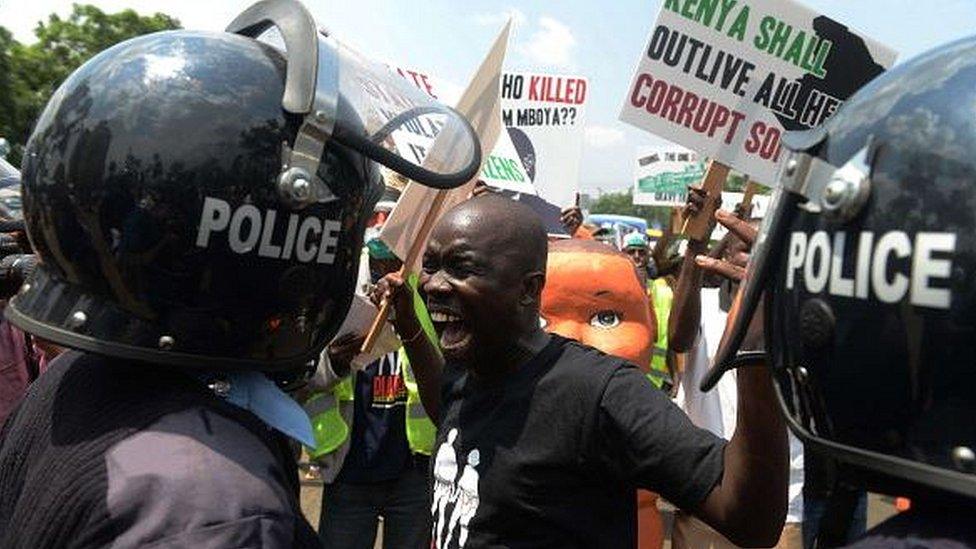

The slogan, painted on a placard carried recently by civil society protesters, captures the kind of attacks the Kenyan judiciary has had to endure in recent days.

The men and women who dispense justice have come under fierce scrutiny, following bribery allegations against a supreme court judge.

After reviewing a report by a special committee that looked into the matter, the Judicial Service Commission recommended that Justice Philip Tunoi should face a tribunal.

Its job would be to determine whether or not he received a bribe of $2m (£1.4m) to rule in favour of Evans Kidero, whose election as Nairobi governor was challenged in 2014.

Justice Tunoi denies the allegations and says that he's willing to face the tribunal to prove the allegations are not true.

There is a lot of anger in Kenya over alleged corruption by state officials

Mr Kidero, who became governor in March 2013, has also denied that he paid a bribe to influence the ruling.

In Kenya, Chief Justice Willy Mutunga has been complaining openly about corruption being rife in the judiciary.

But across the border in Tanzania, the president himself is the one leading the charge.

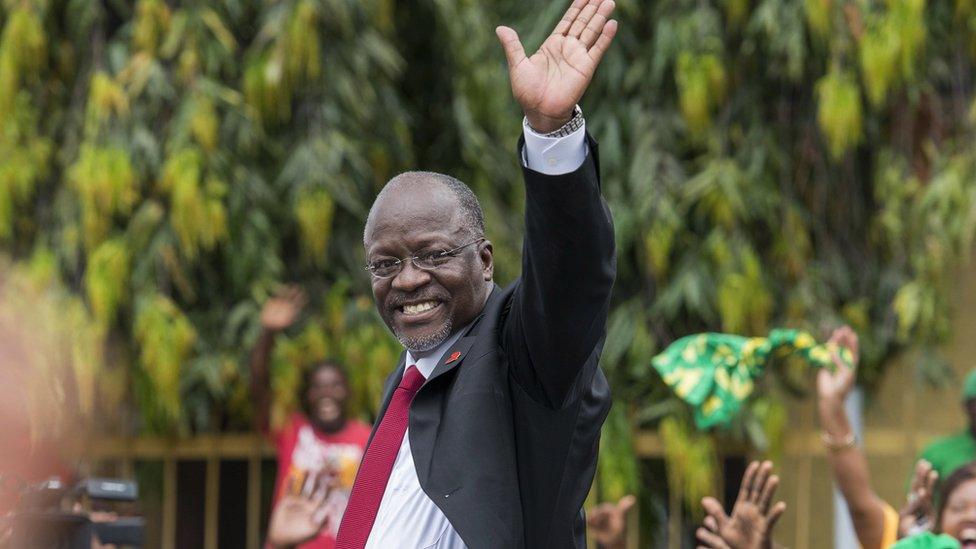

A few days ago, President John Magufuli, who has declared an all-out war against corruption, attacked Tanzania's judicial system, accusing the courts of laziness, bureaucracy and corruption.

"I'm worried that even the people I'm firing because of corruption will easily secure freedom despite watertight evidence against them," the president said.

Tanzania's President John Magufuli has promised to tackle alleged corruption in the judiciary

In Kenya, many argue that whatever the outcome of the tribunal over bribery allegations against Justice Tunoi, the image of the judiciary will be tarred.

In 2012, the country's deputy Chief Justice, Nancy Baraza chose to resign after a tribunal recommended her removal from office "for gross misconduct" over an alleged assault.

Ms Baraza was accused of assaulting a security guard at a shopping mall in Nairobi on New Year's Eve. She denied the allegations, which were never tested in a court of law.

In this case, Justice Tunoi has opted not to resign, but to face his accuser at the tribunal.

Depending on the outcome, the tribunal could have serious implications for the Kenyan judiciary.

Already, the Justice Tunoi saga has taken on a political aspect.

Joseph Warungu:

"The integrity and reputation of the supreme court is critical to political stability in Kenya."

Some voices in the opposition see the affair as an attempt to weaken key institutions of the state, ahead of general elections in 2017.

They argue that if the results of next year's elections are contested, as happened in the 2013 election, it will be the supreme court that will have the final say on who becomes president.

In 2013, the court ruled in favour of President Uhuru Kenyatta, after a petition challenging his victory that was filed by his rival, Raila Odinga.

So, the integrity and reputation of the supreme court is critical to political stability in Kenya.

Luckily for Tanzania's John Magufuli, he is free from such election fever.

He's only been in office for three months and so has no fear about shaking up the judicial system.

Mr Magufuli made it very clear in a speech to judges, magistrates and advocates that he would not interfere with the independence of the judiciary.

But his sharp criticism of the judicial system has sent a signal to that no one will be immune to the reforms he is pursuing in other key sectors of the country.

He also said that he wants money from the courts.

President Magufuli has implied that no-one is immune from his anti-corruption drive

If they processed cases quickly and collected fines efficiently, he said, there would be enough to fund the judiciary properly, and pay for other priorities of his administration.

If Mr Magufuli has his way, the days of judges who receive bribes or delay cases unnecessarily will be numbered.

But due to the country's separation of powers he can't jump in and personally kick out the learned folks.

He has to rely on the chief justice for that.

Meanwhile in Kenya, the country's highest court risks being dragged through the mud, if Justice Tunoi goes through with his plan to face the tribunal.

In fact, the very future of the supreme court could be thrown into doubt if the tribunal were to establish that Justice Tunoi - one of its seven members - had received a bribe.

In Kenya, Chief Justice Willy Mutunga has been a big a champion of reforms in the judiciary, but much to his frustration, he's now learnt that the wheels of justice are designed for the marathon, not the sprint.

And it seems, sometimes the wheels need oiling.

More from Joseph Warungu:

Why Kenya has banned on-air sex

Five gifts for five African presidents