Using talk to tackle Zimbabwe's mental health crisis

- Published

Dr Chibanda says the simple act of talking can make a huge difference to a person's life

Years of economic hardship and inadequate health services in Zimbabwe have contributed to a mental health crisis.

But one unique project is using talking therapy to help thousands of people who would otherwise have been left untreated.

"Some of the myths include witchcraft... people think they are possessed with evil spirits," says Dr Dixon Chibanda, a psychiatrist in the capital, Harare, explaining the traditional beliefs which persist among many over the causes of mental illness.

"But we know there is overwhelming evidence to show that when someone is mentally ill, whether they have common mental disorders or schizophrenia... it is a medical condition which can be controlled."

The World Health Organization's estimates that one in four people will suffer mental health problems at some point in their lives, the figures for Africa would run into the hundreds of millions.

'Overwhelmed'

Dr Chibanda co-founded the Friendship Bench, a network of community health workers, volunteers and specialists, about a decade ago when Zimbabwe's economic turmoil was at its worst.

The programme works by training non-professional carers in talking therapy techniques, so that they can provide treatment.

"We have managed to show that we can train lay health workers to deliver... structured psychotherapy in Africa and produce amazing results," he says.

The initiative has reached 10,000 people so far, but Dr Chibanda hopes the number will increase to as much as 50,000 people each month once the scheme rolls out nationwide.

The scheme focuses on empowering people to work through their own problems

"There is lack of awareness of what can be done for people who are mentally ill... not only in Zimbabwe, but in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa," he says, referring to the absence of both diagnosis and treatment for such illnesses in many parts of the continent.

"Some people in our society who are living with HIV and Aids, unemployed, without access to health care, with a child who is unable to go to school," he says.

"They are overwhelmed and they do not know which problem to start working on."

Family rejection

The simple act of talking can make a huge difference to a person's life, Dr Chibanda insists.

Friendship Bench carers use a programme of talking therapy called "Vazukuru", meaning "nephew" in the local Shona language.

The three stages of Vazukuru talking therapy

Kuvhura pfungwa - Opening up the mind

Kusimbisa - Uplifting the individual

Kusimbisisa - Further strengthening

The treatment is broken down into different stages so that patients can understand the root cause of the mental health issues before trying to find solutions.

"'Kuvhura pfungwa' is the first thing that we do; we open up a person's mind," Dr Chibanda explains.

"From opening a person's mind, we uplift the person, and once they are in a situation where they can deal with the problem, we can then strengthen them. That's 'Kusimbisa'."

"After that, we provide further strengthening which is called 'Kusimbisisa'," he told the BBC.

One of those who received help from the scheme is Chipo, a mother of four living in a Harare township.

'Locked out'

Chipo, which is not her real name, was a victim of domestic violence, and went into a depression that presented mental challenges, which she says reduced her to a "laughing stock" in her community.

More on mental health

Explained: What is mental health and where can I go for help?

Mood assessment: Could I be depressed?

In The Mind:, external BBC News special report (or follow "Mental health" tag in the BBC News app)

"I was hospitalised… it really affected me. I had stress. When my husband went out, he would leave me without anything to eat with the kids, so that I fell ill and almost died," Chipo says.

"I left [town] for my rural home. I had to go to my parent's home. When I arrived there, I really suffered.

"There was my sister who was staying there. She locked me out of the house. I had to sleep outside for the whole night with the kids."

Chipo had divorced and so her sister felt she could not help or accommodate her.

"I spent most of the time crying, crying," she said.

"At one time I also thought of committing suicide because I thought it was the end of life."

But then she was thrown a lifeline by Rutendo, also not her real name, a non-professional carer who had received the training from Friendship Bench.

Years of economic hardship have taken their toll on many Zimbabweans

Rutendo was able to provide Chipo with talking therapy to help her understand her problems, suggesting self-help projects that would help her get back control over her life.

Rutendo says it is an approach that is bearing fruit, despite the scale of the challenge.

"Many young children fall into early marriages, money becomes a problem and domestic violence ensues.

"We teach some of them self-help projects, and how to manage their depression and come out of mental illness, and it's working. Through talking therapy, people come out of their problems."

Chipo responded well to the treatment, engaging with the self-help projects and eventually recovering to the point that she was able to send all her children to school.

"My son did exceptionally well in his results and got a place to study psychology at university," Chipo says proudly, adding her only complaint was that he had not chosen law.

'No need for medication'

Dr Chibanda, standing alongside, lets out a chuckle, replying: "He should study psychology, we need more like him to help us with our work."

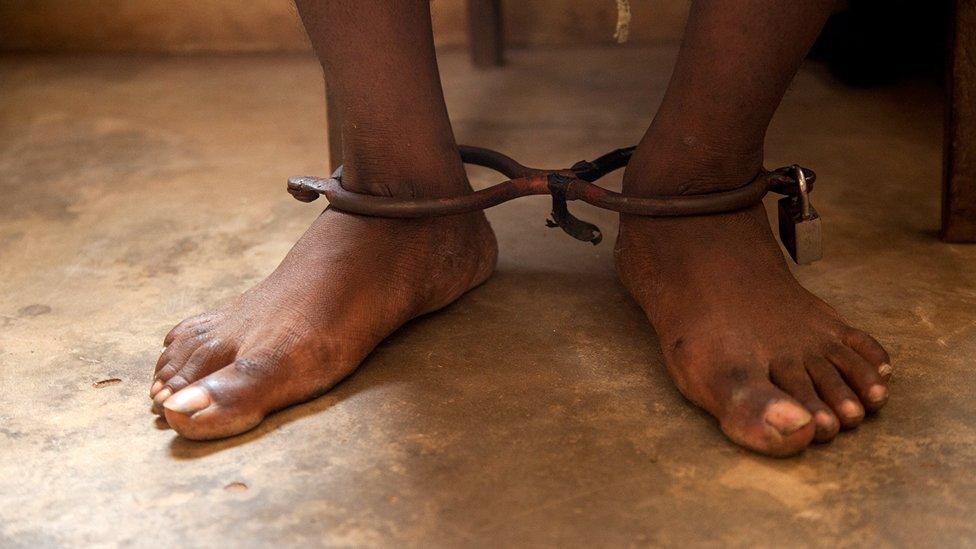

Patients suffering from more severe forms of mental illness are often violent and tend to be shunned by society.

Dr Chibanda offers an alternative to the traditional way such patients are dealt with.

"You can do a lot in the community without locking up people. Half the time, if you talk to them properly, in a structured evidence-based approach, you actually get good results. You don't need to give them medication," he says.

The economic difficulties faced by millions of Zimbabweans, with its knock-on effects for people's mental health, is not likely to improve in the near future, with southern Africa currently facing the worst drought in decades.

But Dr Chibanda hopes that however bad things get, at least the Friendship Bench can give Zimbabweans somewhere to turn to for help.

- Published12 February 2016

- Published12 February 2016

- Published17 February 2016

- Published30 August 2023