Can Nigeria breathe new life into its factories?

- Published

Martin Patience takes a tour of Kano's disused Gaskiya factory

Nigeria, haunted by high unemployment and a sinking oil-dependent economy, is pushing to diversify its economy with a "made in Nigeria" manufacturing campaign. The BBC's Martin Patience went to the northern city of Kano to see what difference it will make.

Cobwebs brushed against my face and dust covered my shoes as I was taken around the Gaskiya textile plant, a ghost factory since its closure in 2005.

Kano used to be one of Africa's great commercial hubs. The former emirate was famed for its fabrics drawing merchants from across the Sahara.

Kano's glorious past lives on through traditions like these horsemen accompanying a royal wedding.

But in recent decades, the winds of global trade have blown through the city, leaving devastation in their wake.

Gaskiya employed 5,000 people who churned out African prints and school and military uniforms until it shut.

In the face of competition from China, large-scale smuggling and high production costs, dozens of factories were forced to close their doors and tens of thousands of workers lost their jobs.

'Things need to change'

In one section of the factory stood row upon row of weaving looms - more than a hundred in total. They took up a floor the size of a football pitch.

A former worker, who did not want to be named, showed me around the building and told me the dilapidation left him feeling devastated.

"When I was working here my country had a future, it had hope," he said.

"I'm a product of this factory, I got an education here, I got married here and my children are from here."

Kano has been a centre for dyeing cloth for many years

I ask him whether he thinks his children could ever work here. "Things will need to change dramatically," he told me, "that is what we are praying for."

Our voices echoed through a plant where the once thunderous machinery was now silent.

The roof was ripped off and the machinery - exposed to the elements - was left rusting in the sun.

The decaying factory was a poignant symbol of how far the once mighty textile industry in Kano has fallen.

Nigeria in numbers:

Population - 178 million - largest in Africa

Africa's biggest oil exporter and largest economy

Oil accounts for 90% of Nigeria's exports and is roughly 75% of the country's revenue

2014: Oil and gas output declined by about 1.3%, after 2013 decline of 13%

GDP per capita: $3,000 (2013), World Bank

Sources: World Bank, Opec

'Survival of the fittest'

Africa's largest economy is reeling from the slump in the global oil prices - growth is at its slowest pace in more than a decade.

But while it is probably too late for Gaskiya factory, there is a glimmer of hope for the industry.

The Nigerian government wants to revive the country's manufacturing base in an effort to diversify the economy.

It is pushing a campaign of "made in Nigeria" to support domestic firms.

The government hopes a "Made in Nigeria" campaign will create more jobs

One of the companies that may benefit is the Terytex factory - one of just a handful of textile businesses still operating in the city.

The firm makes towels and sheets for hospitals and hotels. It currently runs at half its capacity, employing 200 workers.

The managing director, Mohammed Sani Ahmed, is a man who appears surprised that the firm has survived.

He told me he was recently called to a board meeting. "I thought I was going to get crucified for not performing," he said.

"But I ended up receiving praise. We thought this company would have closed last year."

Running a factory in Nigeria is survival of the fittest. Terytex spends half a million dollars a year on fuel for generators because the national grid does not supply enough power.

And then, when the products are made, there are high costs to get them to market.

Mr Ahmed's latest problem: He cannot get foreign currency to buy machine parts from Europe.

While he is grateful that the government is trying to bolster the industry, he is sceptical about the plans.

"We have a history of beautiful policies but implementation is bad," he said.

"We are not afraid of the Chinese but let them pay proper duties and then we can compete."

Nigeria desperately needs to create jobs - almost two million young people enter the job market every year.

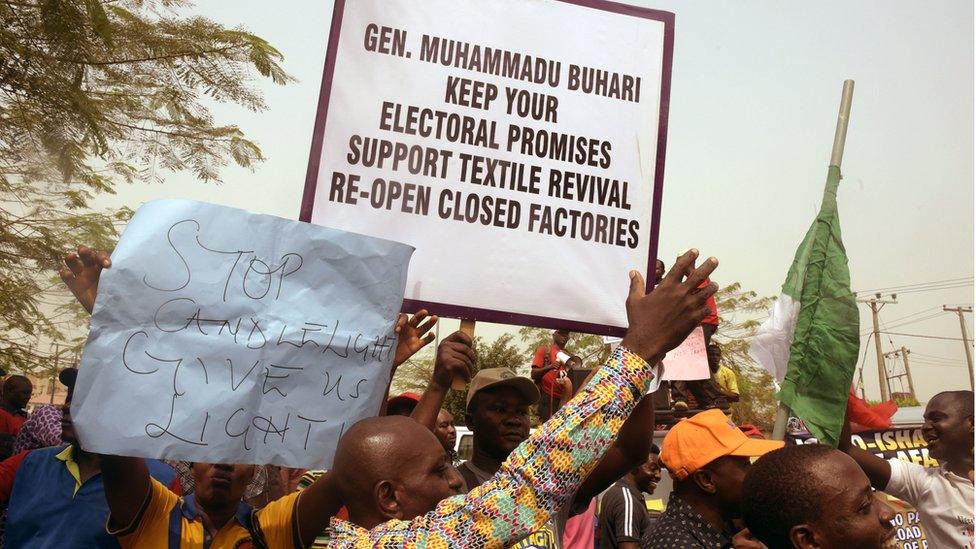

February demonstrations calling for President Buhari to keep electoral promises of a textile revival by re-opening closed factories.

In Kano it is not difficult to spot young men with time on their hands.

One of them, Nuhu Ibrahim, said: "If you don't have contacts with the government or if you don't have anyone that can back you up in terms of business and education it's really hard."

And that is the challenge for the government: Either fix the economy or face growing unrest.

Large swathes of northern Nigeria have been devastated by the Boko Haram insurgency, fuelled in part by soaring unemployment.

Kano is a city with a glorious past but its future looks less bright.

- Published4 February 2016

- Published28 July 2023