Africa's top Twitter moments of the past decade

- Published

It is 10 years since the micro-blogging site Twitter started. But it is not all Justin Bieber and One Direction fans.

Some of Twitter's most significant moments of the last decade - from revolution to revelling - have been felt in Africa:

#Kony2012

A campaign to find Ugandan rebel leader Joseph Kony, who roams central Africa, used the hastags #Kony2012 and #StopKony.

They linked to a half-hour film, external about his Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), which is made up of abducted child soldiers.

The aim of the campaign by US activists was to bring the Ugandan to justice at the International Criminal Court, where he is charged with crimes against humanity.

The video is widely cited as being the fastest-growing viral video of all time.

It reached 100 million views in six days, and 3.7 million people pledged their support for efforts to arrest Mr Kony, says Invisible Children, the organisation behind the video, external.

This was partly achieved through celebrity endorsement by people with a lot of followers like the Bajan singer Rihanna:

The campaign was heavily criticised. One person to ridicule it was English TV critic Charlie Brooker who pointed out, external at the time: "Joseph Kony left Uganda six years ago which makes it so out of date that they may as well be campaigning to kick Bubble out of Big Brother Two".

Four years on, Mr Kony is still at large. The British Telegraph paper reported at the beginning of March, external that he is believed to be in South Sudan and the LRA Tracker group says more than 200 people in the Central African Republic (CAR) have been abducted by the LRA since January.

#BringBackOurGirls

Tweeters used the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls to call for Nigeria's government to rescue more than 200 girls who were kidnapped by Boko Haram militants from their school in north-eastern town of Chibok in April 2014.

Within two weeks of the hashtag taking off, it was tweeted more than a million times.

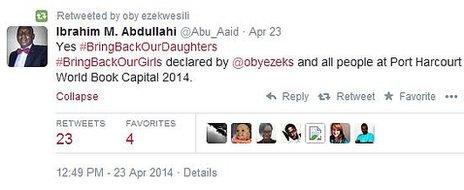

BBC Trending says Nigerian Lawyer Ibrahim M Abdullahi was the very first person to use the hashtag.

After a talk by the former Federal Minister of Education Obiageli Ezekwesili he tweeted this:

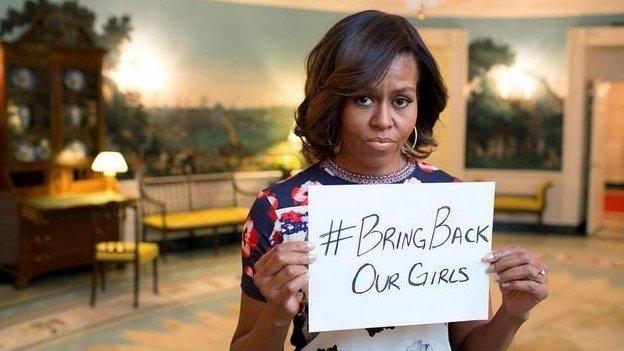

The hashtag went on to be used across the world, including a significant tweet by the US First Lady Michelle Obama:

More than two years on, the girls have yet to be found.

#Jan25

A few popular uprisings have been dubbed "Twitter revolutions" - including Tunisia's Jasmine Revolution of 2011.

Tunisia's President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali stepped down after 23 years in power in January 2011

The BBC reported that this was a victory over state censorship - won by using proxy servers to get around the government's attempt to block Tunisians from posting about the protests online.

The president stood down.

Thousands of Egyptians joined protests after an internet campaign inspired by the uprising in Tunisia.

On 25 January 2011 hundreds of thousands of protesters started to gather in Tahrir Square in Egypt's capital, Cairo.

They used the hastag #Jan25.

But then Twitter was blocked in Egypt.

The Twitter company released a statement saying it believed that the open exchange of information and views was a benefit to societies, and helped governments better connect with their people.

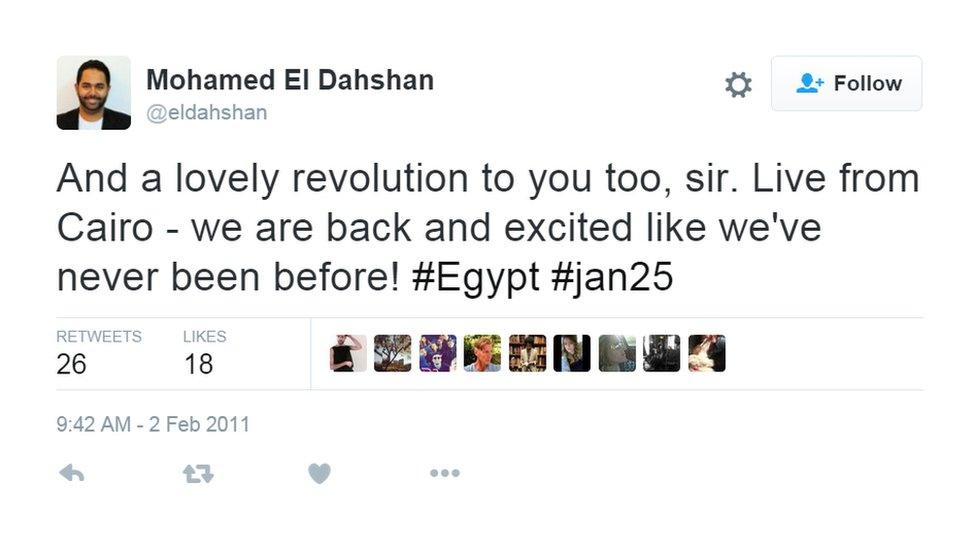

This tweet has been picked out by the company today for marking when Twitter came back online in Egypt:

Beyond 25 January, the hashtag prevailed:

Egypt's long-time President Hosni Mubarak stood down and similar protests followed in 10 other countries, in the so-called Arab Spring.

#OccupyNigeria

At the beginning of 2012 a group of young, well-educated Nigerians organised themselves on Twitter using the hashtag #OccupyNigeria and forced the government to restore some of the fuel subsidy they had withdrawn.

Protesters gathering in such numbers as in the #OccupyNigeria demonstrations is unheard of Nigeria

Nigerian leaders being held to account surprised some Nigeria-watchers at the time. Rarely had there been anything as unifying as the fuel subsidy protests.

The then-head of the central bank, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, and then-Finance Minister Ngozi Okonji-Iweala were forced to explain their actions on TV.

"When you have a former top World Bank official and minister of finance begging the Nigerian people for their trust, you know times have changed. And when the man voted Central Bank Governor of 2010 appears humbled and contrite, it is time to sit up and take notice," wrote the BBC's Nkem Ifejika at the time.

#NigeriaDecides

Tweeters in Nigeria continued to flex their muscles last year as they watched President Goodluck Jonathan peacefully hand over power to opposition candidate Muhammadu Buhari after elections last March.

Every twist and turn of the vote was tweeted with the hashtag #Nigeriadecides.

The person who read out the count results also became a celebrity among tweeters.

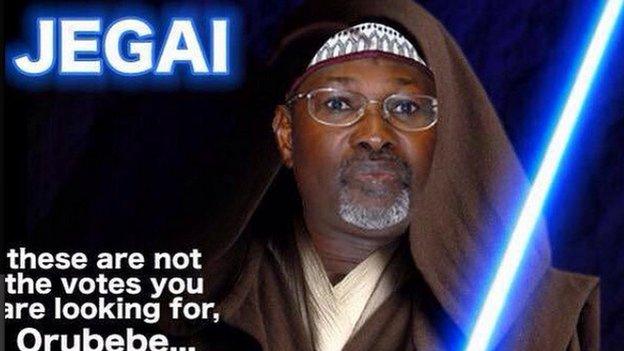

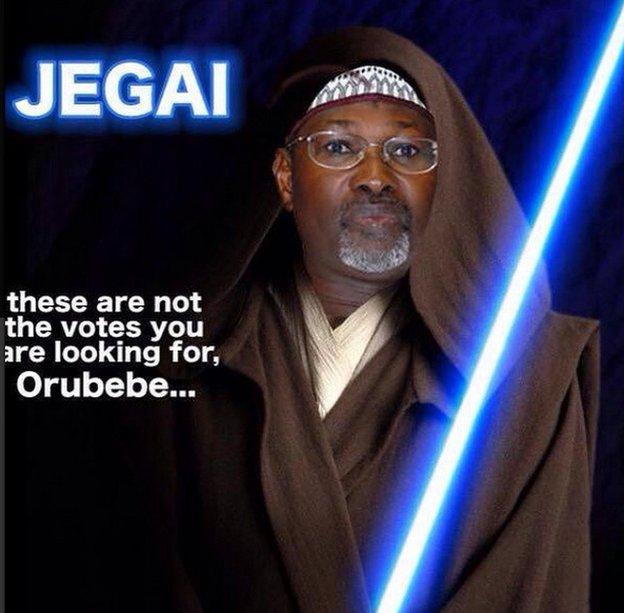

Then-electoral chief Attahiru Jega's calm amid a storm was elevated to super-hero status:

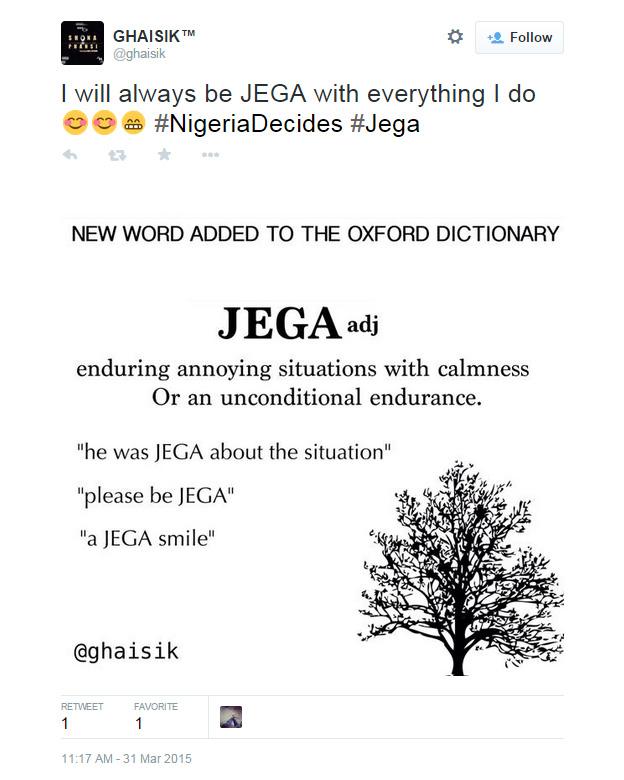

And a new verb was created after his response to PDP Elder Orubebe interrupting the announcement of results, accusing him of bias:

The peaceful transition was declared on Twitter the only way tweeters know how - by changing the hashtag from #Nigeriadecides to #Nigeriadecided

#KOT

Kenyans on Twitter affectionately refer to themselves as #KOT - and they are not to be messed with

The group has become a ferocious part of the Twitter landscape, often campaigning about a perceived injustice.

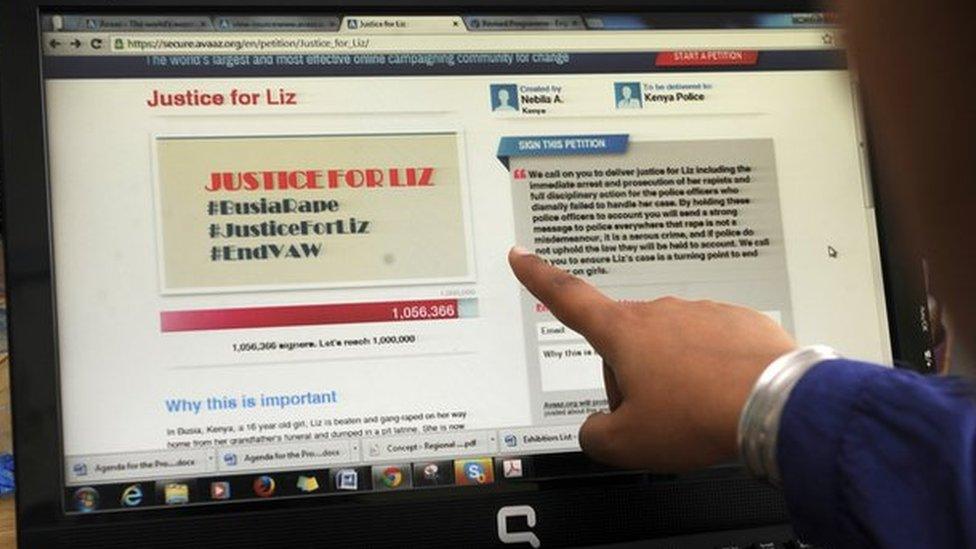

In one such case in 2013, they demanded justice after three men accused of gang-raping a 16-year-old were ordered by police to cut grass as punishment.

They used the hashtag #Justice4Liz and an online petition got more than a million signatures, reported BBC Trending.

Last year, the men each received 15-year jail terms.

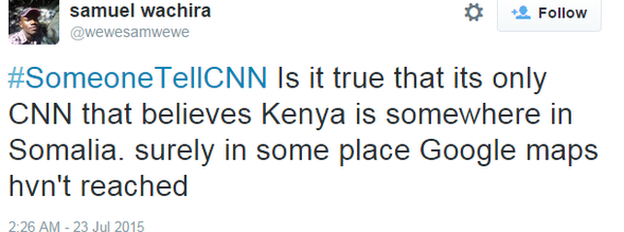

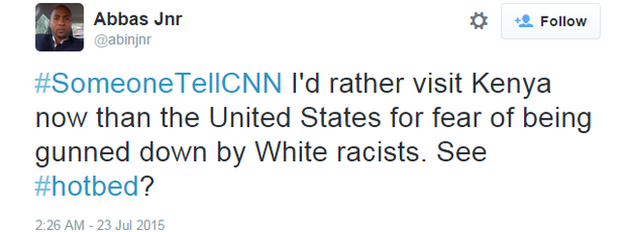

Kenyans on Twitter are also not afraid to take on the international media. The hashtag #SomeonetellCNN trended worldwide last year as tweeters condemned the news organisation for calling the East Africa nation a "hotbed of terror".

It led to the CNN's Global Executive Vice-President Tony Maddox apologising in person to Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta, who tweeted:

Burkina Faso's 'little bird'

Kenyans aren't the only African tweeters to create a community of their compatriots. People in Burkina Faso use the hashtag #lwili when discussing the news to do with the country. We first spotted it in tweets about the coup in 2015.

BBC Africa's Leone Ouedraogo, who is from Burkina Faso, says it is a word in the Moore language, which is widely spoken in the West African nation, and means "little bird".

So we suspect lwili may have been chosen to reflect Twitter's logo.

#FeesMustFall

The hasthag #FeesmMustFall was used to rally support for South African street protests in opposition to a proposed hike in fees for university students in 2015.

Top universities were closed down as the protests spread to 10 institutions across the country.

When the police cracked down on protesters, that too was tweeted, external:

President Jacob Zuma backed down, agreeing to freeze the fees increase, and the hashtag changed to #FeesHaveFallen:

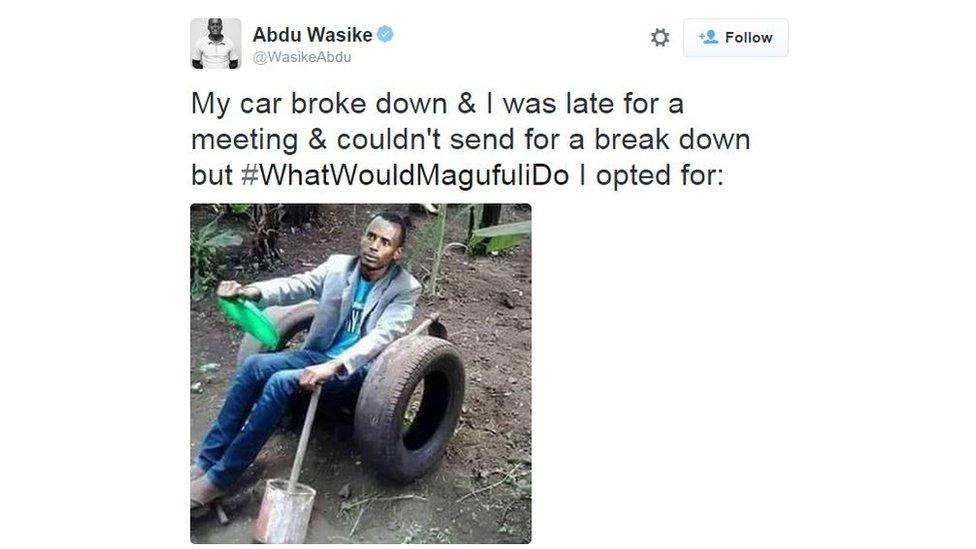

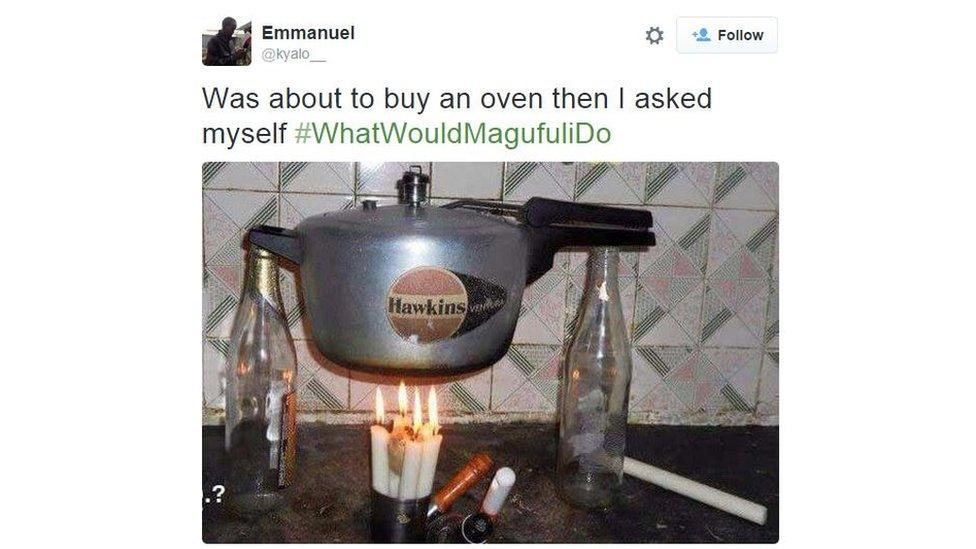

#WhatWouldMagufuliDo

The hashtag #WhatWouldMagafuliDo spread across the continent at the end of last year to make fun of the new Tanzanian president's money-saving plans.

A month after taking office, Mr Magufuli had cancelled the country's independence day celebrations because he thought they were a waste of money.

Instead, he cleaned the streets on 9 December and encouraged his compatriots to do likewise.

John Magufuli has been been nicknamed "The Bulldozer" for his no-nonsense approach

- Published1 April 2015