South Africa unease plays out on campus

- Published

Karen Allen reports on the divisions over race, language and identity at South Africa's universities

Three young women, immaculately dressed for a day in the office rather than an afternoon on campus, chat and laugh during a break from class. It has been a testing few months.

Like a number of other students across South Africa, they have seen their university thrust into the headlines.

Statues have been torn down, fights with an ugly racial hue have broken out during "varsity" sports events, external, and well-rehearsed debates about race and segregation have pushed their way back on to the national agenda. All this when they have been trying to sit exams.

The language the young women seem most comfortable chatting in, Afrikaans, has found itself back in the spotlight.

The women speaking it are "coloured", mixed race, and from a group who increasingly make up the bulk of Afrikaans speakers - 13% of the population now claim it as their first language.

South Africa's top six mother-tongue languages:

Zulu: 22.7%, Xhosa: 16%, Afrikaans: 13.5%, English: 9.6%, Setswana: 8%, Sesotho: 7.6%

South Africa has 11 official languages altogether

English is the most commonly spoken language used officially and in business

Source: SA.info/Census 2011

Geraldine Meyers laughs and gives up trying to trace her ancestry for me - she finds it ridiculous that South Africa still defines everything in terms of race.

But it is a stubborn vestige of South Africa's troubled past, and it exudes from every pore, even if it is not always spoken about.

Plans to drop Afrikaans as a teaching language have prompted protests

"Most people expect me to respond to them in Sesotho or Xhosa [both official South African languages] or English because I'm from the Eastern Cape," says Ms Meyers.

"Instead, I choose to speak Afrikaans socially and English academically, it just makes sense - that is where the jobs will be."

A little over a week ago Ms Meyers' university - the University of the Free State (UFS) in Bloomfontein - took the dramatic step of dropping Afrikaans as a medium of instruction, leaving English alone as the primary teaching language.

For radical political groups such as the Economic Freedom Fighters, it's a victory against white oppression. For many others, the decision was purely pragmatic.

Series of controversies

So why has Afrikaans become the latest expression of unease in South Africa's universities?

First, it was university fees that saw the eruption of protests back in October, then demonstrations over staff contracts, and now language.

Plans to hike university fees prompted violence

Prof Cheryl De La Rey, vice-chancellor of Pretoria University - which, like UFS, is grappling with the language issue - says two forces are at play.

"We have seen the emergence of new political players: it is an election year, we have local government elections in the months ahead," she says.

"But South Africa is also still in transition, there are issues of identity in the post-[19]94 generation and we need to ask questions about what this means for the future leadership of South Africa."

South Africa's leadership has been lurching from crisis to crisis in recent months.

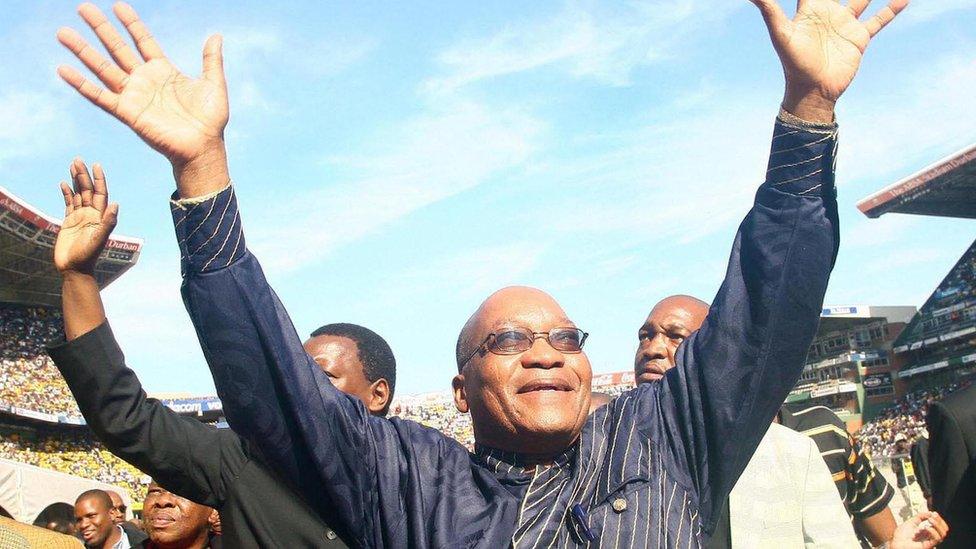

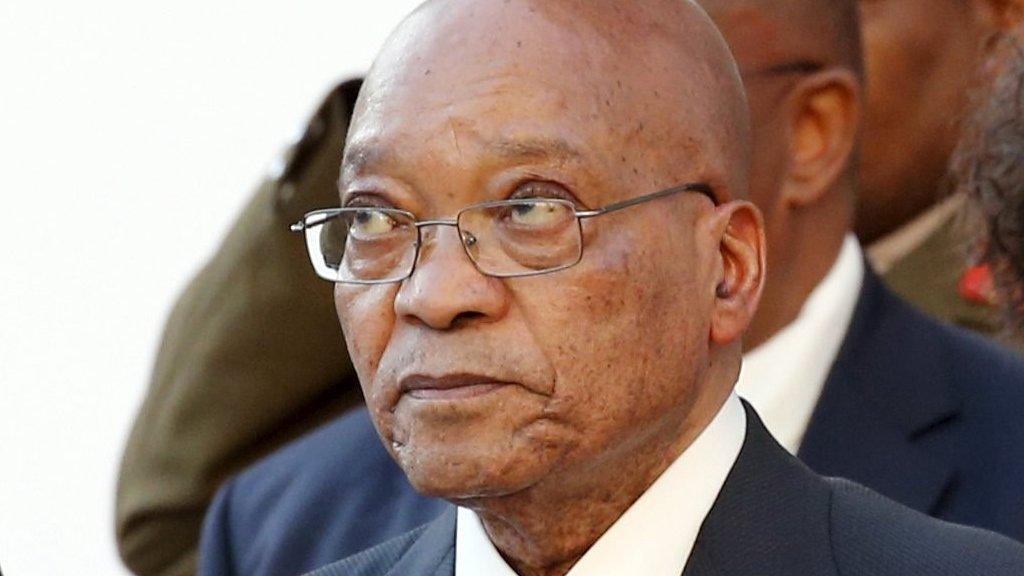

President Zuma has attracted a series of negative headlines

President Jacob Zuma has found himself in the firing line over alleged shadowy business deals and questions about executive oversight.

The top brass of the governing ANC don't seem to have the stomach to confront the issue full on, and have closed ranks.

So, the protests on campus appear to be a manifestation of a wider sense of frustration and malaise.

Racial silos

At UFS, once a bastion of what, in protest parlance, is dubbed "white privilege", Ms Meyers and her friends feel deeply troubled that race is once again the focus of student unrest.

Once a majority white institution, there are now more non-white faces on campus, as part of a programme of affirmative action.

The halls of residence have become more mixed, thanks in part to a visionary vice-chancellor, Jonathan Jansen, the first black man to hold the job.

But in recent weeks, Ms Meyers has noticed a perceptible shift as people retreat back into their racial silos.

It came to a head last month when a university rugby match descended into racial violence.

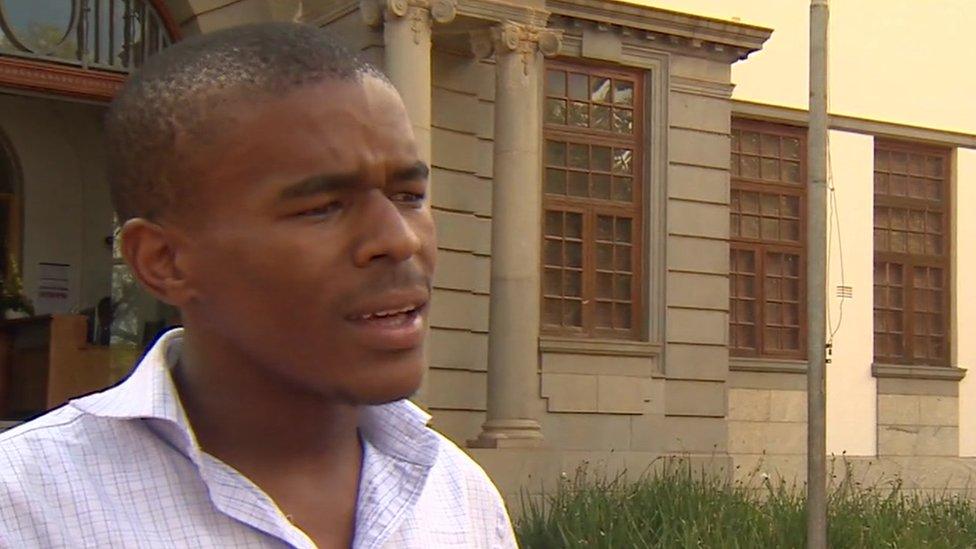

Sinxololo Gcilitshana says race is being used to cloud debate about South Africa's future

Like many others, Ms Meyers believes political activists egged on by supporters outside campus were among those trying to stir things up - because the racial violence doesn't reflect her own experience.

"Outbreaks like this one, really make us move backwards... it feels like three steps forward two steps back," she says.

It is a view shared by white UFS students. A short walk through the manicured grounds of the university and one stumbles across statues to past white leaders.

But a statue of apartheid-era figure CR Swart , externalwas among several torn down at the university in February - in a move echoing the removal of a Cecil Rhodes statue , externalat the University of Capetown.

Jani Swart (no relation) feels strongly the university needs to continue to confront its past, if people are to move on.

"Many of the buildings are still named after political figures from apartheid, and I can understand why some students are upset about it," she says.

Ms Swart's black student colleague Sinxololo Gcilitshana is irritated race is being used to mask what he feels is rigorous political debate about where South Africa is heading.

"When I, as a black student, disagree very much with other black students, they label me as a sellout," he says.

I have heard the same uttered from white mouths.

Divisions of the past

In June, South Africa will mark 40 years since the 1976 Soweto uprising, external, when black students refused to accept Afrikaans - imposed on them by the apartheid government - as the language of learning.

It was one of the most troubled moments during the fight for equality, infamously captured in the disturbing image of 13-year-old Hector Pieterson, shot dead by police.

The Soweto Uprising:

Students began to protest in the streets of Soweto on the morning of 16 June 1976 in response to the introduction of Afrikaans as the teaching language in local schools

The move was deeply resented as Afrikaans was seen by many black South Africans as the language of the oppressor

An estimated 20,000 students took part in the protests. They were met with fierce police brutality

The number of protesters who died is officially 176 - but some estimates put the figure as high as 700

16 June is now a public holiday in South Africa, named Youth Day, in remembrance of the events of 1976

Fast forward to 2016, and it feels like little has changed. But, of course, it has. Maybe just not fast enough for many South Africans.

South Africa has made great strides since the Soweto uprising 40 years ago

Kallie Kriel, from Afriforum, the Afrikaans civil rights group, accepts his community is blamed for the troubles of the past, but fears the democratic gains shepherded in by the late President Nelson Mandela could be eroded.

He says abandoning Afrikaans at university is unfortunate, and fears it will open the door to more intolerance.

"If a small group of radials can demonise a language, it also means the people who speak that language are also demonised," he says.

South Africa is still shackled by the divisions of the past.

But is the unrest playing out on university campuses prompted by frustration over the slow pace of reform, or is a leadership void being exploited for political gain, using race as a trump card?

My guess it that it could well be both.

- Published16 February 2016

- Published21 October 2015

- Published2 September 2015

- Published11 April 2015