South Sudanese want peace - and ice cream

- Published

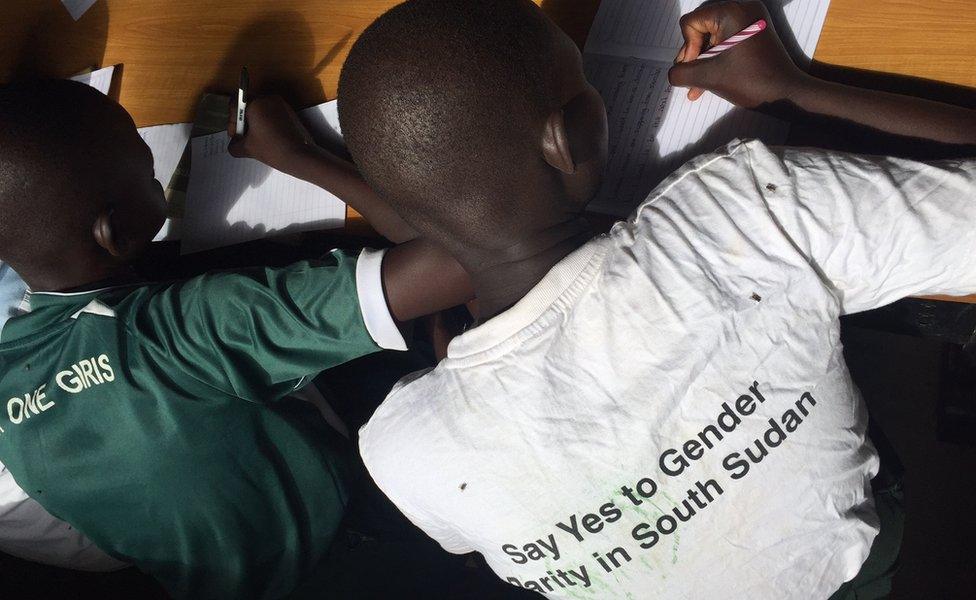

A new era for South Sudan? The girls of Juba One primary school hope so

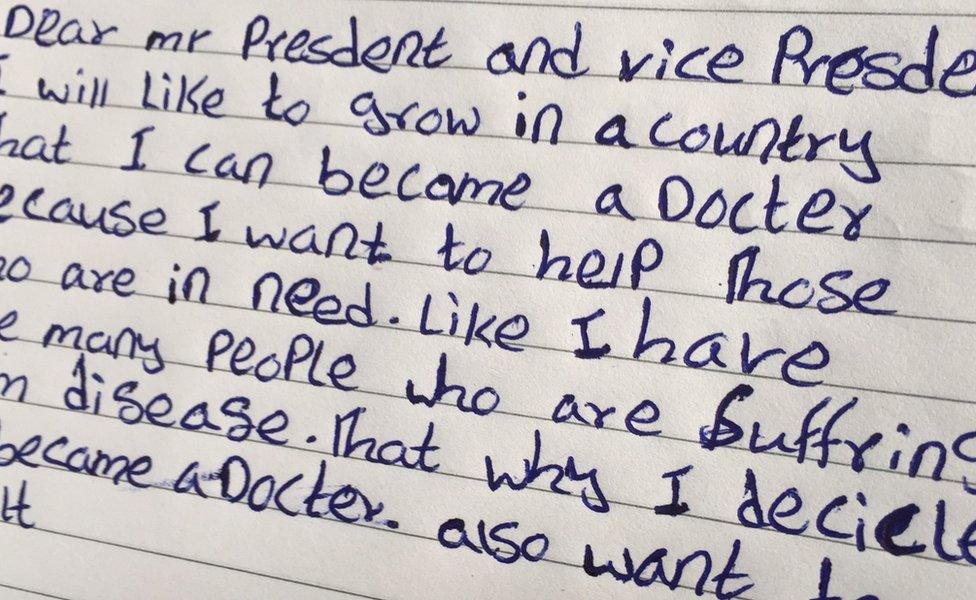

Stop the war, stop tribalism - and we need more chocolate and ice cream. That's what the girls of the Juba One primary school want for this new era in South Sudan.

The return to Juba of rebel leader Riek Machar is allowing many South Sudanese to dream of a better future, whether it's plentiful sweet treats, or a more stable, more prosperous country.

But, inevitably given the bitter nature of South Sudan's civil war and the legacy of past conflicts, the risk of future problems remains high.

First, the good news.

Now Mr Machar has been sworn in as first vice-president, a transitional government of national unity can be formed.

The government is meant to oversee a transitional period leading up to elections in 30 months time - a possible future source of tension given Mr Machar's seeming determination to become president and President Salva Kiir's apparent refusal to countenance this.

The rival military forces will need to be integrated into one body.

This won't be easy if the body language of the government and rebel troops at the airport when Mr Machar arrived is anything to go by. They stood stiffly a couple of metres apart, refusing to acknowledge their former adversaries.

The new government is also meant to set up a hybrid court, to try those accused of the worst atrocities, as well as a national healing and reconciliation programme.

None of this will be straightforward.

Deja-vu

Mr Machar's return was delayed because of days of disagreements, another reminder of mistrust. There was also no obvious warmth when Mr Machar and Mr Kiir greeted each other during the latter's investiture.

The main protagonists have been here before.

Mr Machar led a breakaway group in 1991 during the liberation struggle against the Sudanese government.

Afterwards he came back into the fold, serving as Mr Kiir's vice-president.

It wasn't smooth. As one minister at the time explained to me, Mr Kiir and Mr Machar essentially ran separate systems within government.

It was this tension, in part, that exploded in 2013, first when Mr Kiir sacked his deputy, and then when the war broke out a few months later.

Riek Machar: What you need to know

Studied at UK's University of Bradford, obtaining a PhD in philosophy and strategic planning in 1984

Married UK aid worker Emma McCune in 1991; she died while pregnant

Switched sides on several occasions during the north-south conflict as he sought to strengthen his position and that of his Nuer ethnic group

Sacked as South Sudan's vice-president in July 2013

Denied he was plotting a coup in December 2013 - but his fallout with President Kiir led to more than two-years of conflict

Sworn in again as vice-president in April 2016 as part of an internationally brokered peace deal

"The war today is very much driven by past conflicts, and unresolved issues with past conflicts," says David Deng, of the South Sudan Law Society.

South Sudanese history is studded with examples of powerful men falling out, fighting each other, then joining up to form a common cause.

"It's like a revolving door of violence and politics where, the more successful one is at violence, the more one is rewarded in the context of a peace process," Mr Deng says.

The uneasy cohabitation in this new government might stall, splutter - or roar into more healthy life.

If it brings peace - an end to the rampaging soldiers, rapes and ethnic massacres - then for this alone it will be considered a success.

That's far from certain though.

Economic malaise

As well as the possibility that there will be renewed clashes between forces nominally loyal to the president and his new first vice-president, a number of other apparently separate rebel movements have sprung up in recent months.

The stiffness between Riek Machar (L) and Salva Kiir (R) tells its own story

The government will also have to cope with a disastrous economic situation.

A 50kg bag of sugar sold for 100 South Sudanese pounds ($16; $10) before the war broke out in December 2013, before rising to 500. That price dropped to 450 once Mr Machar returned - a reminder of the way politics and the economy are intertwined.

South Sudanese politicians hope the international community will pour in money once the government is formed, but in this, they may be disappointed.

The falling world oil price, and South Sudan's costly deal to export oil through neighbouring Sudan's pipelines, mean the country's only major export is almost worthless too.

There's another problem.

The peace agreement essentially restored the old order of politicians who governed the country before the conflict.

So there may not be fundamental change, more a return to the frustrations of that period.

David Riing Gai is one of the more than two million people displaced by the conflict.

He's building a house, a roof of overlapping grass layers and walls of mud and timber. But this new home is not a happy one. It's behind barbed wire, in a UN camp for displaced people on the outskirts of Juba.

Even the arrival of Mr Machar isn't enough to convince Mr Riing that things have dramatically improved.

The price of goods fluctuates with the political climate

"I don't believe that this country of ours can be peaceful even for a short time," he says.

"So I have decided to stay here under protection. It was not my intention to be a displaced person in my own country. I was born in the war and I grew up in the war, and this is my country. So for me it is very, very bad."

He hopes his children will have a better life, but he's not optimistic.

The new government - and whatever administration follows it - will have to reunite a very divided country.

Mr Riing and most of the others in that camp say they were targeted simply because they were from the same ethnic group as Mr Machar, the Nuer.

One of Mr Riing's friends, Stephen, said eight members of his family were killed, simply because they were Nuer, in the first few days of the war.

"For me, to think properly as a normal human will take time," Stephen admits.

Many Dinka - the ethnic group of President Kiir - have been killed because of their ethnicity by the largely Nuer rebels too.

On a basketball court with fading paint in Juba, I met Acuil Banggol, a Dinka, and William Deng, a Nuer, who said they had been friends since 1977, and refused to let politics divide them.

In the basketball courts, schools, markets, villages and - yes - military camps of South Sudan, people are desperate for real peace.

That longing, and with it the pressure on politicians tied to their local communities, might be this country's best chance of peace, growth - and maybe a bit more ice cream.