Uganda, where a book can cost a month’s salary

- Published

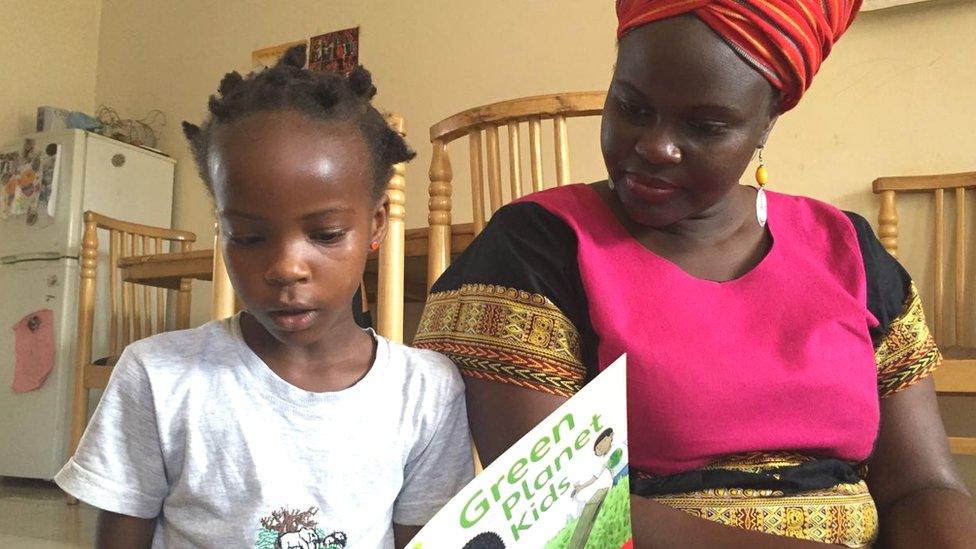

It is hard for parents like Beverley Nambozo to afford to buy books

The hunt for a good book in Uganda's capital is not for the faint-hearted; in fact it feels like a black market.

People look for friends going on a foreign trip to help them buy books, which are either not available or too expensive in Kampala.

One book which I have been wanting to read is Nothing Left To Steal by South African journalist Mzilikazi wa Afrika.

But it costs around 140,000 Ugandan shillings ($42, £29) in bookshops here - which can buy a week's worth of groceries for a family.

On internet shopping sites the best-selling memoir goes for less than a third of that price but deliveries to Uganda are not straightforward.

I did splurge once on a book by Guinea's revolutionary leader Ahmed Sekou Toure. It set me back $60 - the pan-Africanist in me got the better of me that day.

Waitresses in downtown Kampala barely earn $60 in a month.

Library books by motorbike

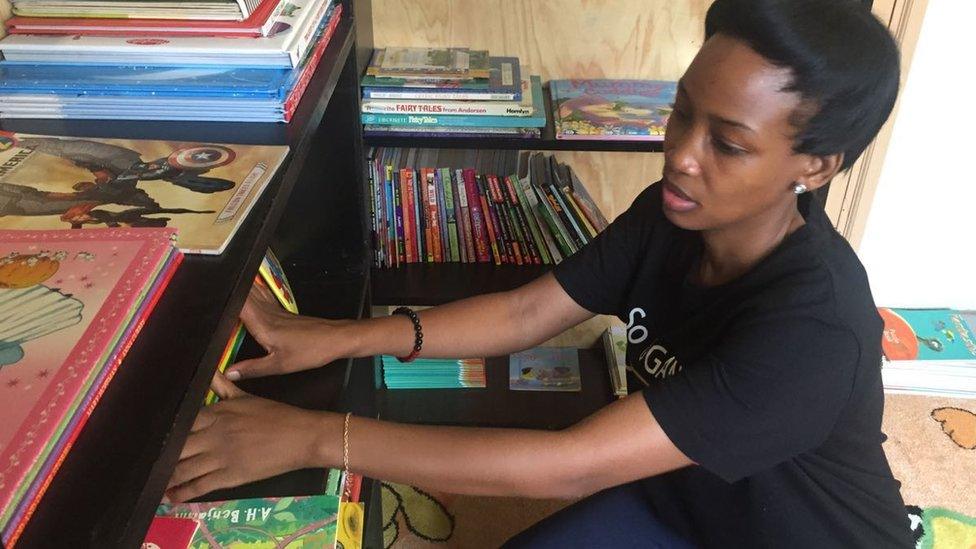

It is in this environment that Rosey Sembatya has decided to start the Malaika Children's Mobile Library.

"My sister has four children now and I've been finding it very difficult to buy them books because they're quite expensive," she says.

"So I sat back and thought maybe there is need to create something that can make story books accessible and available at a quite cheap price."

Rosey Sembatya charges an annual $30 fee for children to read three books a week

The library is in the spare room of a two-bedroom house she rents.

There are a couple of hundred books stacked on shelves and a long desk.

From here motorbike taxis, known as boda bodas, whizz around the capital delivering a week's worth of reading for children.

Ms Sembatya used up her savings to start the library and says she tries to keep the cost down.

For a $30 annual fee, each child can borrow three books a week.

She wants schemes like hers to stop reading being regarded as a purely middle-class luxury.

"It is because it has a cost implication. Yet it shouldn't be. Once one has a child they need to learn, they need to read."

Bookpoint in Kampala could be taken for a shop in London or New York

But Uganda does have a fairly robust publishing industry.

Fountain Publishers is one of the biggest in East Africa, but like most companies here its focus is on academic writing.

Its main production office is at Makerere University, the country's main higher institute of learning.

"Our biggest sellers are the curriculum books. Schools and students cannot afford to go away minus curriculum books," Harrison Kiggundu, the firm's senior marketing officer, told me.

They are then loath to spend extra money on other books.

"It has had a great impact on bringing down the reading culture," he says.

But it is not only about price. Getting Ugandans reading for pleasure is the challenge.

As Mr Kiggundu says, after years of cramming textbooks many people do not want to open another book after their studies.

Changing attitudes

With the advent of social media and the wider availability of the internet, Ugandans are reading snippets on their phones, laptops or tablets rather than picking up a novel.

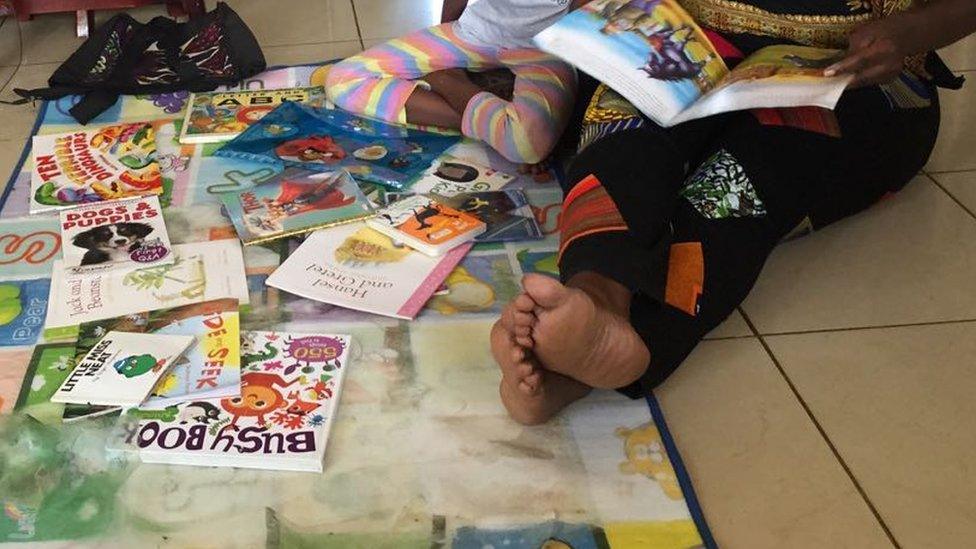

But there are people willing to invest in reading.

Some Ugandans are willing to buy books for their children even if they are not big readers

At one of the new upmarket malls in Kampala, Christina Kakeeto opened up Bookpoint a few years ago.

The bookshop's shelves are stacked with international bestsellers, classics and popular African novels - it could be in London or New York.

A civil engineer, Ms Kakeeto gave up her career to start this venture and says she tries to keep prices close to those on international markets - though these are too high for many Ugandans.

But she says as some Ugandans get wealthier, they are willing to buy books especially for their children.

This is also happening with parents who are not necessarily readers themselves as they were not read to as children.

"I'm encouraged that they are teaching their children to read. The cost remains a challenge," she tells me.

'More confident'

Beverley Nambozo and her husband are an example of parents trying to make sure their children grow up with a healthy habit for reading.

Their daughters, Zion aged seven and four-year-old Raziela, are signed up to the Malaika Children's Mobile Library.

As a poet Ms Nambozo knows the value of words and she is adamant that reading for fun will give her girls a brighter future.

"Having these creative books with children reading, you just see how they are learning more about themselves, about their environment, improving on their vocabulary and becoming confident as well," she says.

So Uganda appears caught in a Catch-22 situation.

People seem to read more when they have the money and know the value of reading for personal success.

But to make decent money, it helps to be educated and able to read.

- Published26 April 2023