The first South Africans fight for their rights

- Published

William Stanley Peterson explains why he has formed his party

Control of the land is at the heart of politics in South Africa and a new party is calling for justice for the country's oldest inhabitants.

"We want our land back," William Stanley Peterson, president of the Khoisan Revolution party, shouts into a microphone.

A small and noisy crowds has gathered around the short stocky man in a jackal-skin hat and colourful blazer on a small dusty street lined with corrugated tin shacks

The 45-year-old has a receptive audience, after all this area is known as Khoisan village and it is where he lives in a shack with his family.

Mr Peterson's party is a new one - it was registered in February but they are busy trying to gain momentum here in the Northern Cape province of South Africa.

They were formed to compete in August's local elections and are focusing their campaign around two key issues - land and language.

The Khoisan are South Africa's oldest inhabitants and are made up of a number of related communities: The Cape Khoi; the Nama; the Koranna; the Griqua and the San - who also often refer to themselves as bushmen.

The Khoisan are traditionally hunter-gatherers, living from the land

History has been hard on them, they were dispossessed by the colonialists and oppressed under white-minority rule, and now they say they are being marginalised in South Africa.

There are no official figures for how many South Africans are of Khoisan origin.

Under apartheid, they were classified as "coloured" or mixed race, and their indigenous languages and traditions were lost as they were forced to assimilate.

Most now speak Afrikaans as their first language.

"As the Khoisan people, we are the first and oldest nation in South Africa," says Mr Peterson as we shelter from the midday sun outside a traditional San hut near the small town of Upington.

William Peterson is confident the local community will support him

"There's no recognition or acknowledgement for us so that's a sore story. Everybody and every government is failing us.

"We want to claim back our land and govern ourselves. When I look at all the fences across the land I feel like I'm in jail."

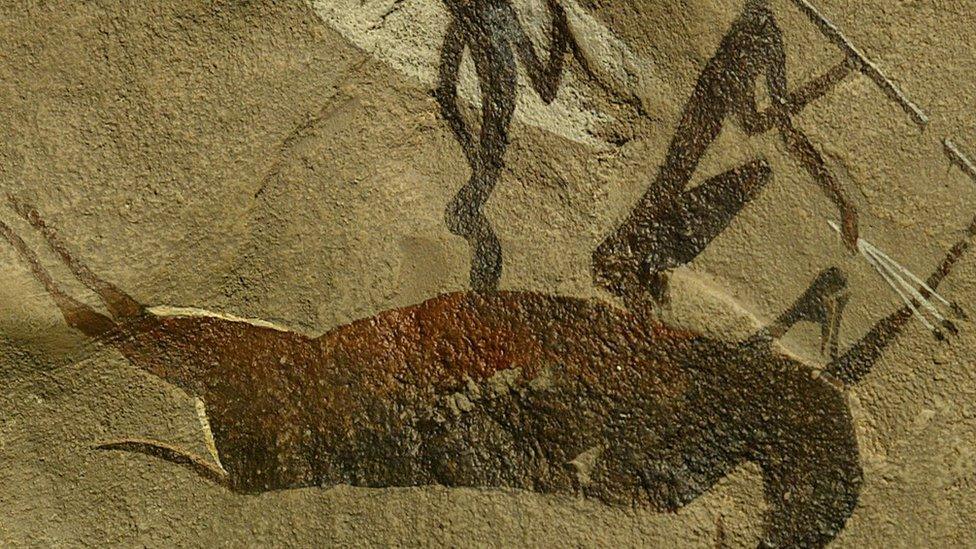

He is adamant that the rock paintings that dot the country serve as the Khoisan's title deeds.

"If we win the elections here, the first thing we will do is ask the owners of the mines from who did they buy the land?

"We as the Khoisan should own that land. We will cut off their utilities and force them to close until they agree to negotiate with us and recognise that they are on our land."

A six-hour drive from Upington, through stark, rock-strewn countryside is the small town of Steinkopf.

It is close to the Namibian border and is at the heart of South Africa's Nama community.

The Khoisan Revolution are hosting a rally here and with Mr Peterson are a number of his closest party leaders including !Xaru !Khusi.

He is a former special forces soldier and is dressed in a traditional San loincloth with a bow and arrows strapped across his bare back.

Anti-hunting laws have made it more difficult for the Khoisan to carry with their traditional way of life

The Khoisan Revolution is campaigning around two key issues - land and language

The local community clap and cheer as he emerges from the back of a pick-up truck and sings a song heavy with clicks and sounds unpronounceable to most non-Khoisan.

I ask him what it means.

"It's a song that's close to our heart, I'm telling the people how the bushmen were hunted by the colonialists, how we are living, how we are still struggling."

Sadly very few people now understand the song.

IXam is considered an extinct Khoisan language and is not one of South Africa's 11 official languages - all of which angers Mr Peterson.

"If you look at South Africa's coat of arms, it says: '!ke e: Ixarra IIke which is the IXam language and means 'united in diversity'.

"You put our language on the coat of arms but you don't recognise it in schools.

"Mandarin Chinese is now being taught while our own indigenous languages are forgotten. It breaks my heart."

On a nearby street corner a group of young men kick a football. I ask if they'll be supporting Mr Peterson and his party in the forthcoming local elections.

"Yes," says one of them, his English uncertain: "Because I'm Khoisan, it's my blood."

The rest of the players nod earnestly.

Back in Khoisan village, Mr Peterson and his colleagues lay on another impromptu political rally.

Rock painting are the Khoisan's title deeds, Mr Peterson says

As music booms from the speakers I wander off to explore the back streets and find out what level of support the party really have.

A young mother in an African National Congress T-shirt stands outside her shack.

"So you won't be voting for the Khoisan revolution?" I ask.

She laughs and looks down at the picture of South African President Jacob Zuma emblazoned across her chest.

"This is just a shirt," she says, "I'll be voting for the Khoisan."

Mr Peterson is confident that he can count on support from his community in the elections and win control of some municipalities.

"In the Northern Cape," he says watching the sunset on the edge of town, "it's not a matter of can we win?

"We know that we will win."

But given the ruling ANC's dominance in all elections since the end of apartheid in 1994, that remains an ambitious target.

Even winning a few seats would represent a major advance and might help put the Khoisan grievances on the national agenda.

- Published7 January 2014

- Published27 January 2011