Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi: The vandal of Timbuktu

- Published

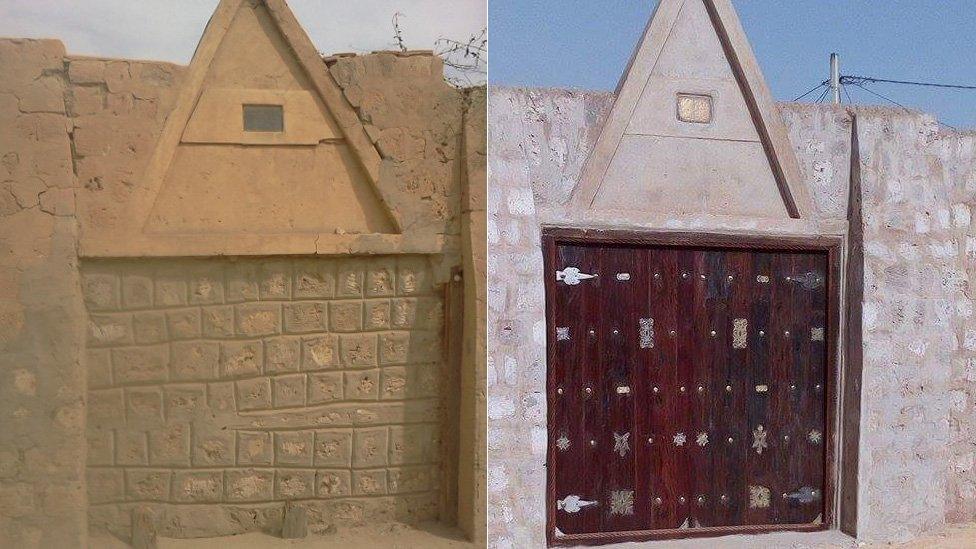

Militants damaged and removed the sacred door of the Sidi Yahia mosque in 2012 (L), but it was restored and reinstated in September 2016 (R)

Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi has pleaded guilty to destroying nine mausoleums and a mosque in Timbuktu, Mali, in the first case concerning damage to cultural artefacts to be heard at the International Criminal Court (ICC). As the trial reaches its verdict, author Nicholas Jubber looks at the man behind the crime.

As head of jihadist group Ansar Dine's moral "accountability" enforcers, known as the the Hisbah, Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi led the destruction of key shrines in 2012.

These included the 16th Century mausoleum of Sidi Mahmoud, who was the rector of Timbuktu's world-famous Sankore University, and the shrine of Sidi Ahmed ar-Raqqad, who wrote a book on traditional pharmacology in the 17th Century and is credited with conjuring a spring that flowed until 1948.

Also destroyed was the door of the 15th Century mosque of Sidi Yahia, who is described as the patron saint of the town. According to local belief, the opening of the mosque door would herald the end of the world.

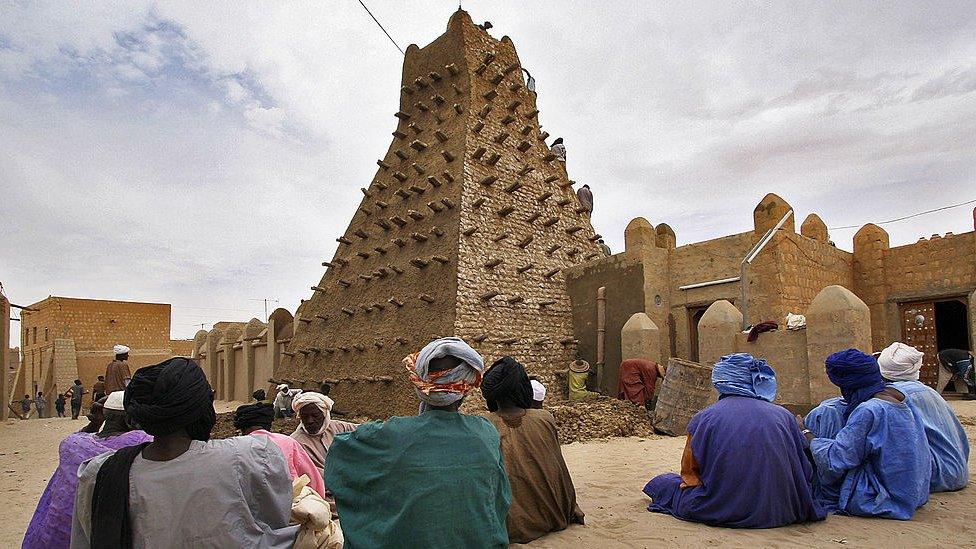

In destroying these sacred places, the jihadists were launching an assault on the Sufi-influenced form of Islam practised in Timbuktu.

Ahmad al-Faqi al-Mahdi said he regretted his actions and asked for forgiveness

Ould Elhadje, a historian of Timbuktu, says that the Malian identity comes from faith in Islam and the the country's "great sages".

The shrines where these sages are buried provide a link between Timbuktu's - and Mali's - past and present.

As Sidi Maiga, a local resident, explains: "We are proud that Timbuktu was founded by Muslims. It has never been a pagan city and our monuments are Muslim ones."

Local pride in the city's heritage made the actions of Ansar Dine all the harder to endure, and is one reason why many in Timbuktu are keen to see justice delivered.

"Wherever they came from," says Mr Elhadje, "the jihadists were imposing Islam from outside the community, and this is against the Sharia."

Mr al-Mahdi is the first individual to be charged at the ICC with "damaging mankind's cultural heritage".

His trial represents a significant benchmark, and a prototype for future prosecutions. It could be applied to those accused of destroying Palmyra in Syria or Nineveh in Iraq.

The Malian conflict illuminated and exacerbated long-standing ethnic tensions, and it is in this respect that Mr al-Mahdi's background is revealing.

Jihadi groups took advantage of a Tuareg rebellion to sieze most of northern Mali

Many of Timbuktu's shrines were destroyed

As a Tuareg, he belongs to the ethnic group credited with pushing for greater development in northern Mali, but blamed for spearheading the Malian crisis.

Although he graduated as a teacher in Timbuktu, he was born in the village of Agouni, 97km (60 miles) west of the city.

According to Niamoyu Toure, a nurse who worked in the village "many bandits came and some of the people joined the jihadists".

Emad Elhadje, who worked at Agouni's school, explains: "People had nothing, and they were suffering very badly. I saw three of my students, in the back of a pick-up truck. They were wearing jihadist uniforms and carrying guns. They said it was necessity.

"There was no trade between the village and the desert, and the jihadists were offering 150,000 CFA ($260, £200) every month to anyone who became a soldier."

Mali timeline

January 2012: Tuareg rebellion in northern Mali begins

March 2012: Military overthrows president over his handling of the rebellion

June 2012: Jihadist groups seize most of northern Mali from the Tuaregs

January 2013: French troops help recapture key towns in the north

August 2013: UN force takes over to insure security in the north

This is the environment from which Mr al-Mahdi emerged: Pastoral communities drained by drought, corruption and political marginalisation, goaded by the prospect of empowerment.

Many took other paths, travelling to more secluded parts of the desert, or joined the 350,000 people displaced by the conflict, gathering in refugee camps across the region.

Some, like Mr al-Mahdi, aligned themselves with the jihadists.

Traditional affiliations tend to guide local responses to the trial.

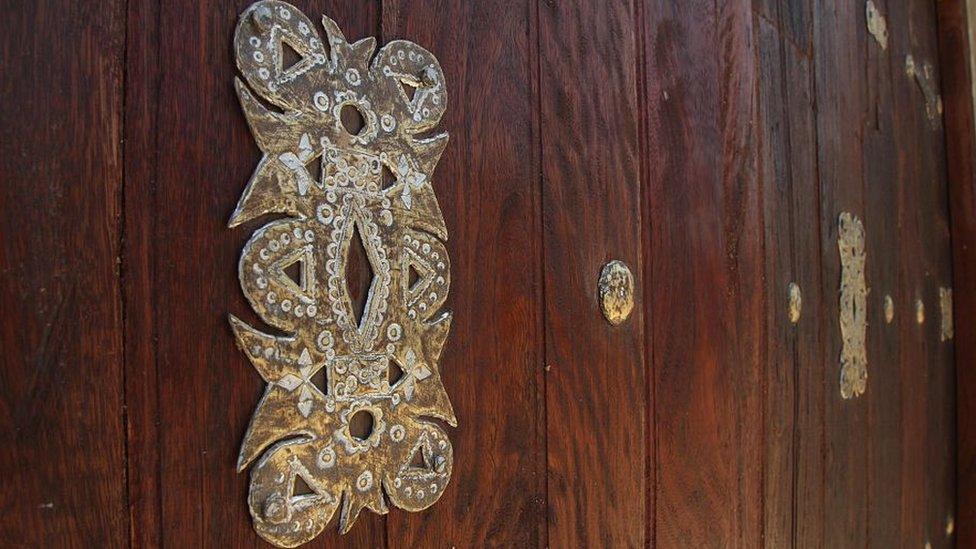

Local craftsmen used old photographs to guide them in the restoration process

While some residents are happy to see a measure of justice for the destruction of the shrines, others are asking why those responsible for other crimes, especially acts of violence against women and minors, have not been held accountable.

Every resident can tell stories of violence experienced or witnessed: From Hady, a student, whipped for talking to her boyfriend in the street, to Abdullah, a tour guide, who lived behind a bank in the centre of town, which was turned into a correctional facility.

"Every night," he recalls, "I could hear screams coming from there."

A restoration process is gradually restoring what was destroyed.

Consulting old photographs and using the testimony of elders, and with the support of the UN's cultural organisation, Unesco, about 100 local craftsmen have already reconstructed many of the shrines, using traditional materials.

Timbuktu's unique architecture is a key part of people's identity there

With remarkable timing, just a few days before the verdict against Mr al-Mahdi was due to be delivered, on 19 September local dignitaries gathered alongside townspeople to inaugurate the restored gate of the Sidi Yahia Mosque, in what Unesco chief Irina Bokova called "a new and decisive step in Mali's reconstruction and peace building work".

"People are happy," says local resident Sidi Maiga, "because it is a return of their identity".

Timbuktu is defined by its shrines, and destroying them was a blow against the town's identity.

For many residents, the restoration programme is a victory against the jihadists who are still at large in parts of northern Mali.

Nicholas Jubber is the author of The Timbuktu School for Nomads

- Published6 May 2012

- Published22 August 2016

- Published4 June 2013

- Published20 November 2015