How Burkina Faso's different religions live in peace

- Published

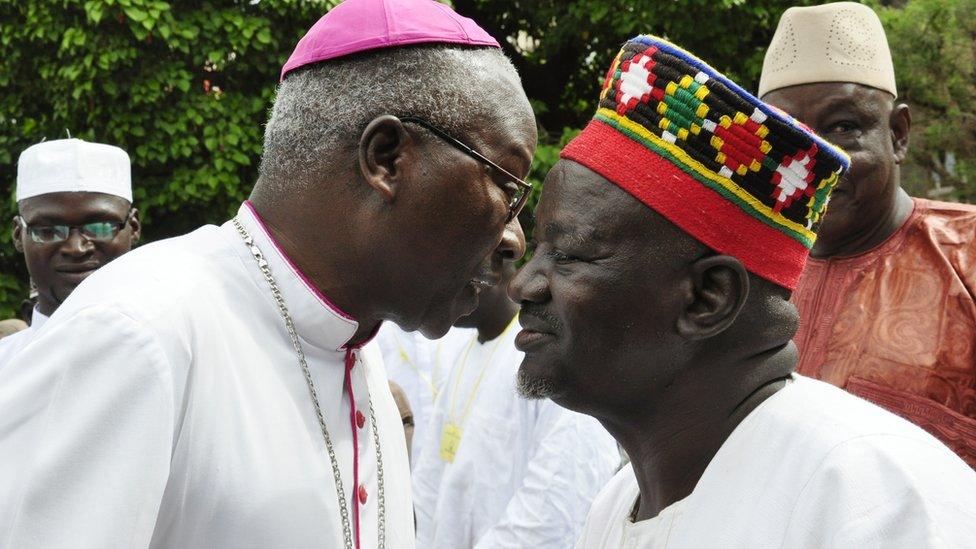

The Archbishop of Ouagadougou wishes a traditional chief a happy Eid

The Pope has invited Burkina Faso's president to the Vatican later this month to see what can be learnt from the West African nation's example of religious tolerance. BBC Africa's Lamine Konkobo is from Burkina Faso and assesses if this can continue in a region under assault from Islamist militant groups.

Religious tolerance has long been wired into the social fabric of my country, with many people drawing their faith from more than a single creed.

The Islam practised by many Burkinabe Muslims - who account for about 60% of the population - would be considered blasphemous by Salafists, as they include many animist practices.

My own father was not born a Muslim. He converted to Islam in the 1970s as a result of his business dealings with El Haj Omar Kanazoe, a rich trader from the Yarse sub-ethnic group known for their affiliation to Islam.

While my father chose to become a Muslim, setting his children up to follow in his footsteps, the rest of his family remained animist and my father could not disown them for that.

Playing a traditional drum, particularly on Eid, might be seen as un-Islamic but in Burkina Faso it is quite acceptable

In the neighbourhood where he chose to set up his household, he was under the tutorship of his maternal uncle, a patriarch named Yandga who was the custodian of the village's fetishes.

Anywhere my father looked, even if his new co-religionists urged him to hate, he could not have done so without losing his soul.

Like many others across the country, he had to adapt to the dynamics of society around him by accepting that Islam was not the only way.

As children, we grew up with people with differing religious beliefs - playing together, being told off by each other's parents, celebrating each other's festivals, mourning each other's deaths, with humanity as the overriding connector common to all.

Survival mechanism

And what is true for my family is also true for millions of others across Burkina Faso. Indeed, religious tolerance has prevailed with sun-rising certainty that we hardly ever pause to consider it.

It is not something that was ever taught. It is an instinctive survival mechanism that occurs naturally among a people so socially interconnected as to leave no chance for religion to play a divisive role.

The January attack on Ouagadougou's Splendid Hotel was a test for religious tolerance

About a quarter of the population is Christian - again with many using animist rites alongside Christian forms of worship.

In terms of identity, most people feel stronger ties to their extended family and ethnic group, than their religion.

However, the International Crisis Group (ICG) said in a report released last month, external that it was concerned that this long tradition of tolerance is now being dangerously tested - in two different ways:

Would the peaceful co-existence survive if the country were to experience another attack by Islamist militants such as the one carried out in January by al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb?

Could the growing frustration of the Muslim community over their under-representation within sectors of the public administration lead to a dangerous radicalisation?

Clearly, these two questions do raise serious cause for concern.

On the danger of external influences such as in the case of random massacres by foreign jihadists, the example of neighbouring Mali serves as a worrying precedent.

Apart from the Tuareg issue in the north, which is more ethnic than religious, Mali had long been known for its religious harmony in much the same way as Burkina Faso.

More on militancy in Africa:

But religious tolerance fell by the wayside when Islamist militants took advantage of the latest Tuareg uprising to seize control of half of the country in 2012.

Across the ancient cities of the north, they enforced Sharia: They banned music; they staged public beatings of those accused of sins such theft and extra-marital sex.

Meanwhile, in the south, which remained free from Islamist insurgents' control, friends and neighbours in the capital, Bamako, who had never thought twice about each other's religious affiliation became suspicious of one another.

Light-skinned Arabs and Tuaregs came to be in danger of being attacked because they were assumed to sympathise with the radicals.

Relations are now slowly improving after the Islamist militant groups were driven out by French-led forces.

So far, the January attack on a luxury hotel in the Burkina capital, Ouagadougou, which killed 30 people, has not fundamentally changed relations between Burkina Faso's Muslims and other communities.

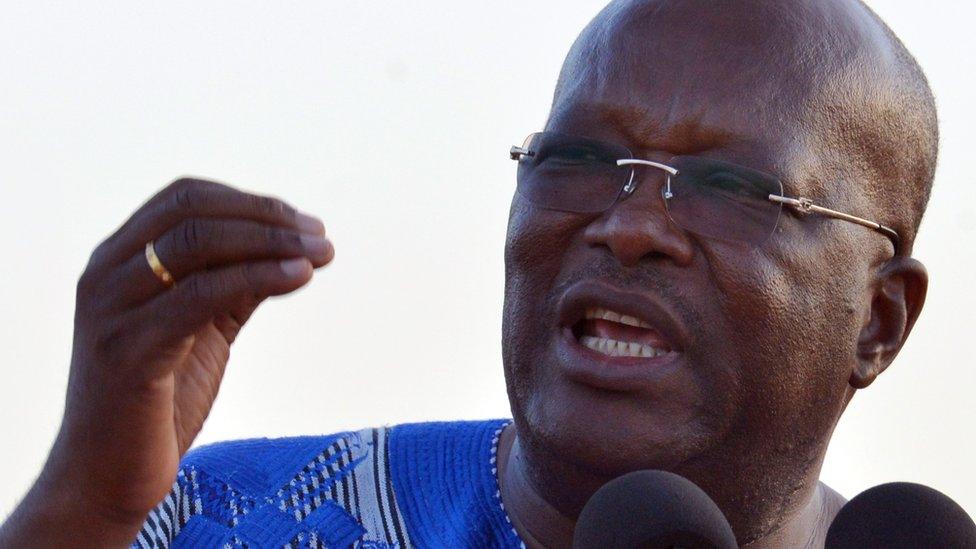

President Roch Marc Kabore is to meet Pope Francis on 20 October

But it has heightened security across the country and started a debate about the danger of religious fundamentalism.

There is a risk that a further attack in the name of Islam might cause fundamental damage to the tradition of religious tolerance in the country.

The ICG report also points to the underrepresentation of Muslims in the civil service as a possible source of future tension.

However, this is not the same nature of threat to religious harmony because it is not the result of deliberate discrimination against the Muslim majority.

It is both the product of the colonial legacy and of the beliefs of an overwhelming number of Muslims who prefer to send their children to Islamic schools, rather than the state system, which could lead to a job with the civil service.

That is an own goal which is unlikely to be blamed on a third party to the effect of fuelling radicalism; unless it were exploited by political or other groups. In which case, the ICG's warning would not be ungrounded.

However, religious tolerance is so deeply engrained in Burkina Faso, that it would take a social big-bang for such a dreaded shift to occur.

A Christmas pig

The closest to religious intolerance I ever witnessed from my converted father was one Christmas, when my brother and I ran to see Uncle Samuel, a Christian, slaughter pigs he had bought for the festive feast.

Five things about landlocked Burkina Faso:

It is renowned for its film festival Fespaco, held every two years in Ouagadougou

A former French colony, it gained independence as Upper Volta in 1960 and its main export is cotton

Capt Thomas Sankara adopted radical left-wing policies during his time in power in the 1980s and is often referred to as "Africa's Che Guevara"

The anti-imperialist revolutionary renamed the country Burkina Faso, which translates as "land of honest men"

People in Burkina Faso, known as Burkinabes, love riding motor scooters.

We were childishly enjoying the spectacle when my father got someone to call us back home.

When we arrived, he looked at us with such severity on the face and scolded:

"Do you have any brains? You went there to see the pigs being killed - for what? So you would one day know how to properly slaughter your own swine? You know you disappoint me children?"

However, when Uncle Samuel shared out the lamb he had bought specially for his Muslim neighbours whom he knew would not touch pork, my father enthusiastically accepted his share.

- Published14 March 2016

- Published30 April 2014

- Published26 February 2024