Africa blighted by multiple Jihadist threats

- Published

Nigerian authorities have had some success targeting Boko Haram camps

Boko Haram was recently rated as the world's most deadly terrorist organisation, external - eclipsing even so-called Islamic State (IS) - but it is far from the only jihadist group posing a threat to stability in Africa.

Based on the situation reports we receive every few days from the Nigerian military, troops are active in destroying dozens, external of Boko Haram camps.

Suspected terror "kingpins" are often arrested and abductees freed. Army press releases also include photographs of the aftermath of these operations.

There has been significant progress in slowing down the killings by the insurgents and keeping them from openly holding territory - considering that this time last year the sect controlled much of the north-eastern state of Borno.

That, however, should not be seen as weakness on the part of Boko Haram.

Its attacks continue sporadically across the region, both in the form of bombings and raids on both military and civilian targets.

The Nigerian authorities must be wondering how this group is able to replenish its weaponry and get its members still to continue audacious and deadly attacks.

Across the border, Cameroon's Rapid Response Force (BIR) has also suffered major setbacks in the fight.

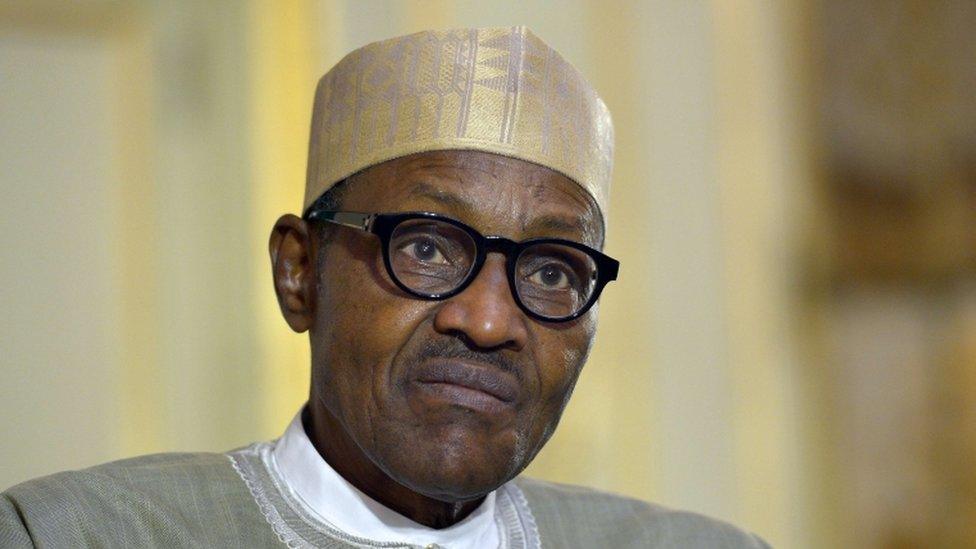

President Buhari has admitted his target to end the conflict by the year's end was too optimistic

Nigeria cannot afford to ignore the large number of insurgents - or the tactical capabilities present within their ranks.

With the continued violence, President Muhammadu Buhari has accepted that the target he set for the military to end the conflict by the end of the year is not achievable.

In a statement, he said: "The timeframe should serve as a guide and if exigency of multiple operations across the country advises a modification, the federal government will not hesitate to do so in order to address new flashpoints that are rearing their ugly heads in some parts of the country."

Jihadists join forces

Nigeria's neighbours in the Lake Chad Basin are also struggling to keep jihadist factions at bay.

The vast Sahel region, which spreads coast to coast across a band of northern Africa, is itself a haven for armed groups from bandits to global extremist franchises.

Among the latter is al-Qaeda in the Maghreb (AQIM), which seemed to be on the back foot, but has recently seen a mending of relations between its offshoots.

Its leader Abdelmalek Droukdel recently announced that AQIM was working with al-Mourabitoun - led by the veteran Algerian jihadist Mokhtar Belmokhtar - to fight against France and its allies in the region.

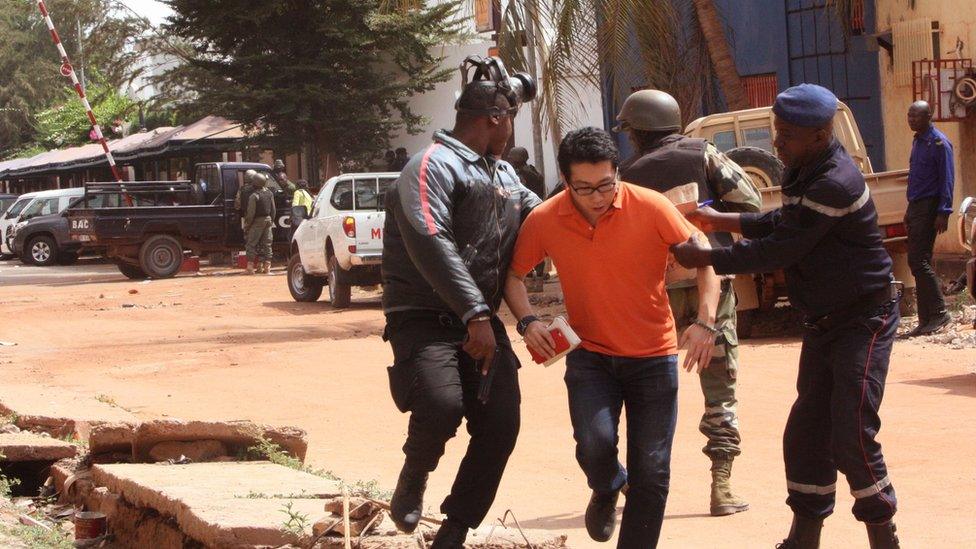

Two Jihadist groups have claimed responsibility for the attack on the Radisson Blu hotel in Bamako

This comes after they claimed to have jointly planned the November attack on the Radisson Blu hotel , externalin Mali's capital Bamako.

This alliance is important for both groups to keep IS from attempting to spread its dominance from North Africa to the Sahel.

Militancy in Mali:

October 2011: Ethnic Tuaregs launch rebellion after returning with arms from Libya

March 2012: Army coup over government's handling of rebellion, a month later Tuareg and al-Qaeda-linked fighters seize control of north

June 2012: Islamist groups capture Timbuktu, Kidal and Gao from Tuaregs, start to destroy Muslim shrines and manuscripts and impose Sharia

January 2013: Islamist fighters capture a central town, raising fears they could reach Bamako. Mali requests French help

July 2013: UN force, now totalling about 12,000, takes over responsibility for securing the north after Islamists routed from towns

July 2014: France launches an operation in the Sahel to stem jihadist groups

Attacks continue in northern desert area, blamed on Tuareg and Islamist groups

2015: Terror attacks in the capital, Bamako, and central Mali

"IS interests in the region have become strong enough that dissenting parties within the AQIM constellation are willing to put aside their grievances and collaborate once again to protect their own interests," says Yan St-Pierre of the international security-consulting group MOSECON.

"This means AQIM will be more aggressive, not necessarily in terms of attacks, but in announcing its presence."

Both groups are competing globally and are likely to attempt to outdo each other even in Africa.

Mokhtar Belmokhtar leads al-Mourabitoun

One theatre where this could be seen is in Somalia, where the al-Qaeda-affiliated militant group al-Shabab has been witnessing dissent within its ranks as some of its members pledge their allegiance to IS.

Since 2006, al-Shabab has been the source of instability in the Horn of Africa but as fresh fissures become increasingly apparent within the group, this fragile nation could potentially be home to two global jihadist movements.

However the number of defections to IS so far is not yet significant enough to change the scene.

The core al-Shabab remains the major threat in the region and the reason for the international military intervention, hence why IS has consistently sought to win them over with its propaganda.

Counterinsurgency needed

As groups in the Sahel and the Horn decide which terror franchise they will sign up to, there is a great need for robust counterinsurgency efforts.

Al-Shabab has had to contend with dissention in its ranks

Military might is vital in the response but evidently has only produced limited results - despite the involvement of world powers like the US and France - and even though it could achieve a lot, people within African armies often point to the challenges in the US interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan as examples as to why it is difficult to suppress insurgencies.

That, however, should not be a dead end - as if Washington's methods are the only way to go.

African governments and their partners should not underestimate the ideological angle - assuming that jihadist insurgencies are driven solely by poverty, even though that is itself an important factor.

As has been seen elsewhere in the world, recruitment into jihadist groups (and sympathy for them) is not exclusive to the marginalised.

As things stand, terrorism will remain in Africa for at least the near future.

- Published20 November 2015