The crack in Gambia's smile

- Published

President Yahya Jammeh has ruled The Gambia since a coup more than 20 years ago

The Gambia is known to tourists as "the smiling coast of West Africa", but this masks something more troubling. On his last trip before his untimely death this week, journalist Chris Simpson navigated the different worlds that exist in the small country.

I had been in The Gambian capital, Banjul, less than an hour and here I was, car pulled over, explaining my business to a group of men in uniform.

A thrillingly sinister start to a week-long holiday? Not quite.

I had fallen into the clutches of the tourist police, identity badges to the fore, courteous to a fault. "Are you lost?" they asked.

They had guessed right.

A 12-hour journey from neighbouring Senegal had taken its toll and I had lost patience with my taxi driver's wearing "welcome to Africa" banter and general cluelessness.

Sheepishly, I agreed to a police escort. The commander jumped in next to the somewhat nonplussed man at the wheel and me, the slightly fake out-of-season tourist.

The Gambia is known to many outside the country as an ideal beach holiday location

We tracked down the pre-booked hotel. I checked in, but not before a semi-stern warning from my new friend: "Only ride in the green taxis designated for tourists; watch yourself, there are lots of cheats and chancers about."

Yes, the con artists, hard-luck stories and fake friends are out there.

Open your heart and your wallet if you must, but show some discrimination. And be mindful that ordinary Gambians have considerably more to fear than you do, never more so than now.

The man they are on the run from, sometimes literally, is President Yahya Jammeh.

He was less than 30 when he took power in 1994, ousting his predecessor, the much older Dawda Jawara. The president is now 51, but middle age has not mellowed him.

Gambian friends told me not to make the common outsider's mistake of treating their leader as a maverick or eccentric - "tyrant" was nearer the mark, they said.

"Every day we think about the president's health... and hope it is getting worse," a Gambian back from long stints abroad remarked.

Diplomats, both western and African, see The Gambia in freefall.

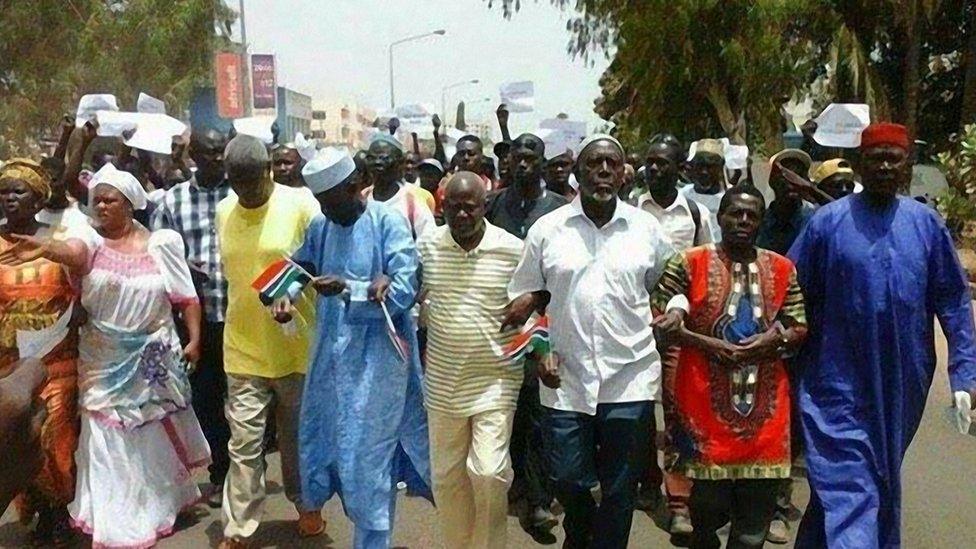

In April, there was a rare street protest after an opposition activist died in custody

The torture testimonies and accounts of citizens gone missing are too widespread and well-documented to be ignored. Huge numbers of Gambians are discreetly leaving, which has become known as "taking the back way".

The last time I had been in Banjul, Gambian journalists had talked openly to me about rough rebukes from the president. They had tried to work out when the threats were serious, and when they were just scare tactics.

This time, I proceeded more cautiously.

A young reporter at an independent paper agreed to an office rendezvous. He steered me into a side room and talked shyly but candidly about the state of the nation and the fear which truth-tellers had to put up with.

For sure, he said, his phone was tapped. His friends often urged each other to soften messages on social media as the security forces are reading, and they do not take kindly to jokes about the leader.

You can find many picture postcard scenes in the country

From Our Own Correspondent has insight and analysis from BBC journalists, correspondents and writers from around the world

Listen on iPlayer, get the podcast or listen on the BBC World Service or on Radio 4 on Saturdays at 11:30 BST

Opposition activists, once loyal to Mr Jammeh, were more bullish.

They told me of the president's petty jealousy, his willingness to turn friends into foes.

They said the people would get rid of him, maybe at the elections in December. But I could not share their confidence.

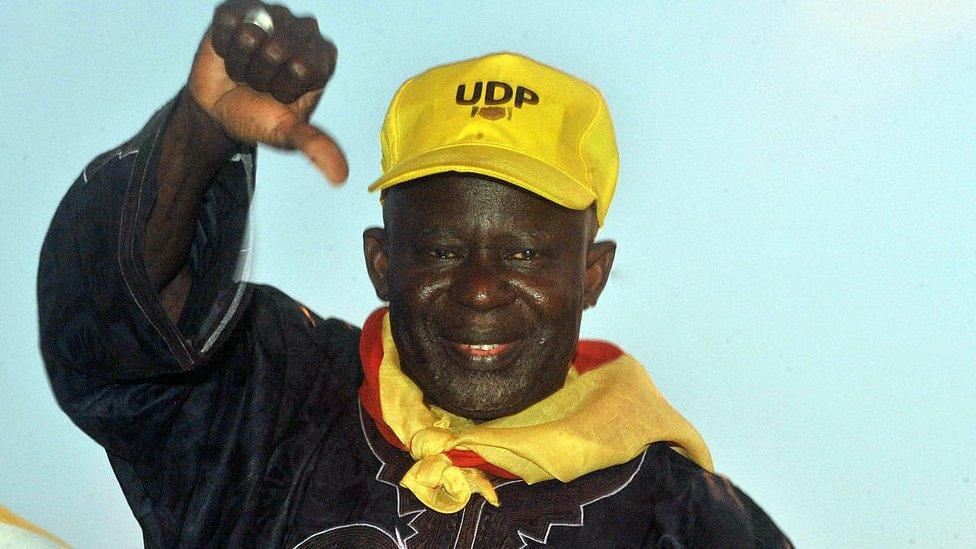

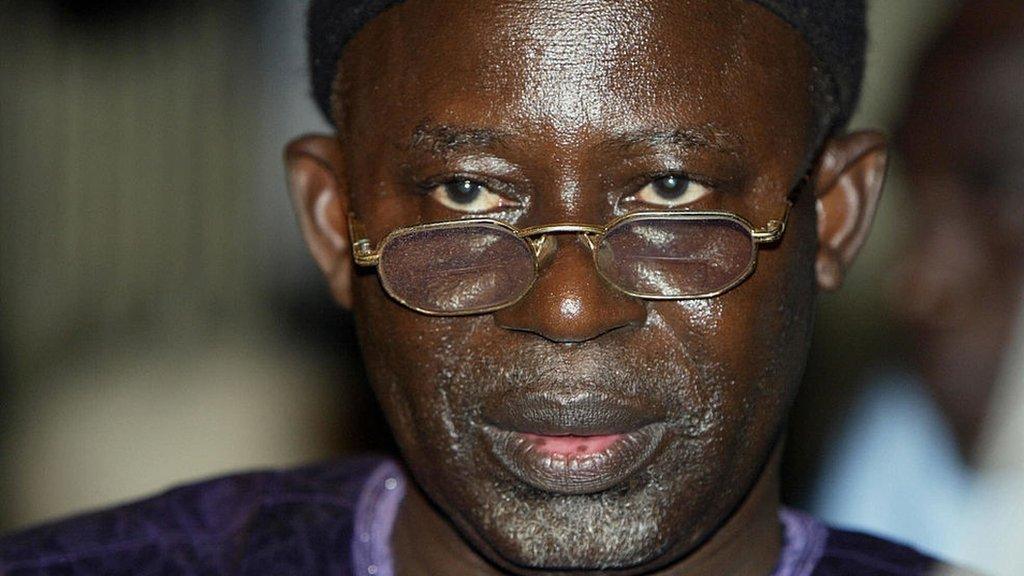

Opposition leader Ousainou Darboe was arrested in April for taking part in an unauthorised demonstration

But how did all this play out in the enclaves patrolled by my friends from the tourist police?

The smallest country on mainland Africa has prided itself on the welcome it extends to visitors. Revenues from tourism account for close to 20% of GDP.

The same package has worked for a long time: Sun-baked beaches, mangrove forests for the more intrepid, the drumming and exotic birdlife.

It is a cut-price paradise; a newly declared Islamic Republic where beer is cheap and sex is openly available to both male and female tourists.

Same-sex relationships, though, are not part of the scene. President Jammeh has volunteered to slit the throats of homosexuals.

On earlier visits, I snobbishly wrote off the tourist belt as toytown Africa, dispiritingly subservient and banal, geared towards clients who are uncurious about the country they were staying in.

This time I tried harder.

Our reporter Chris Simpson did manage to find a friendly crocodile

Resisting the freelance blandishments of chancers promising a glimpse of the real Africa, I signed up for a day tour with the official tourism authorities.

My guides knew their country. Patient, good humoured and informative, they stayed off politics but were no starry-eyed propagandists.

The tour took us from ancient artefacts and historic photographs, to friendly crocodiles and hard-up wood carvers, to an impoverished primary school and an upmarket beach bar.

The sky had more grey than blue and it all felt a little like hard work, as if The Gambia was clinging on to an image everyone knows to be an illusion, while a darker, meaner reality now intrudes.

Chris Simpson died unexpectedly on Wednesday at the age of 53. He had been a correspondent for the BBC in Angola, Rwanda, Senegal and the Central African Republic.

- Published12 April 2023

- Published22 January 2016

- Published21 July 2016

- Published2 June 2016