South Africa to withdraw from war crimes court

- Published

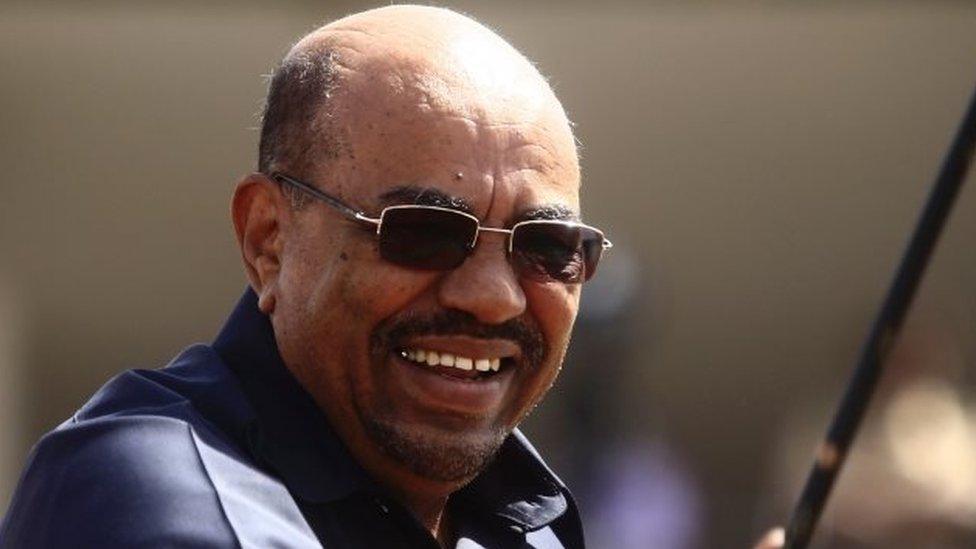

Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir was in South Africa for a meeting of African leaders in 2015

South Africa has formally begun the process of withdrawing from the International Criminal Court (ICC), notifying the UN of its decision.

South Africa did not want to execute ICC arrest warrants which would lead to "regime change", a minister said.

Last year, a South African court criticised the government for refusing to arrest Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir.

He is wanted by the ICC on charges of genocide and war crimes.

Mr Bashir was attending an African Union summit in Johannesburg, when the government ignored an ICC request to arrest him.

He denies allegations that he committed atrocities in Sudan's troubled western Darfur region.

Several media outlets say they have obtained a copy of the "Instrument of Withdrawal", signed by South Africa's foreign minister.

"The Republic of South Africa has found that its obligations with respect to the peaceful resolution of conflicts at times are incompatible with the interpretation given by the International Criminal Court," the document says.

'Runaway train'

Justice Minister Michael Masutha said at a press conference that the government would table legislation in parliament to withdraw South Africa from the ICC.

The Rome Statute, under which the ICC was set up, required the arrest of heads of state for whom a warrant was issued.

The consequence of this would be "regime change" and the statute was incompatible with South African legislation which gave heads of state diplomatic immunity, he added.

Analysis: Anna Holligan, BBC ICC correspondent

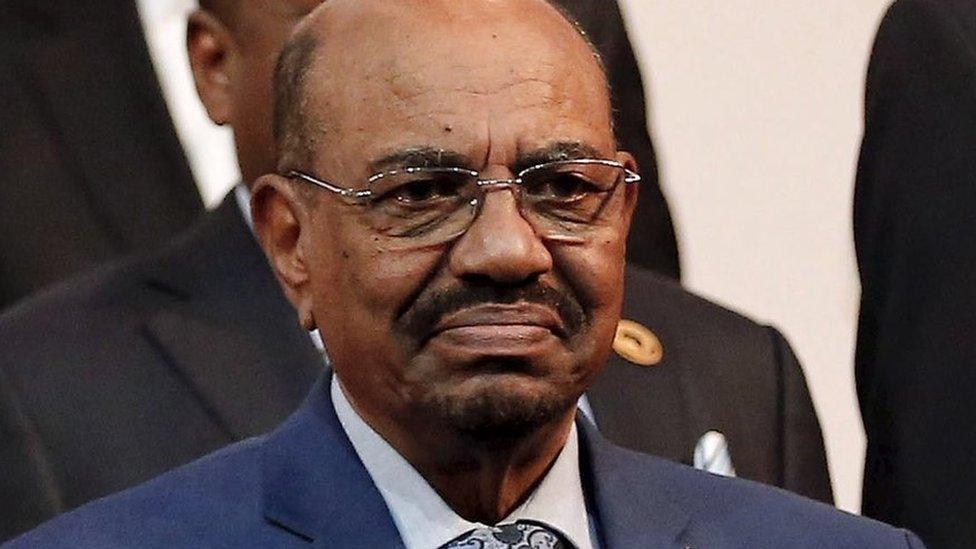

President Zuma recently met his Kenyan counterpart Uhuru Kenyatta, against whom an ICC prosecution failed

The ICC has a notoriously fractious relationship with the African continent. Despite 34 African nations voluntarily signing up to the court's jurisdiction - in recent years a handful of governments have decided their idea of international justice is incompatible with that set out in the Rome Statute.

When the Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta was charged with crimes against humanity, the African Union argued that heads of state should be entitled to immunity for the duration of their term in office, a direct contravention of the ICC's raison d'etre to hold the most powerful to account. The trial against Mr Kenyatta later collapsed because of a lack of evidence.

There were almost farcical scenes when the Sudanese president attended a summit in Johannesburg at the invitation of the African Union, then disappeared during dinner after resounding calls from human rights groups for South Africa to uphold its obligation as a member of the ICC to detain him in line with the outstanding arrest warrant.

It seems this divided loyalty between the competing demands of AU and ICC has driven South Africa to initiate the process of pulling out. Nine out of 10 of the ICC's current investigations are in Africa - leading to allegations of bias against African countries.

So is this the beginning of the end of the world's first permanent war crimes court? The answer will partly depend on whether this withdrawal generates a domino effect.

Human Rights Watch has criticised South Africa's decision.

"South Africa's proposed withdrawal from the International Criminal Court shows startling disregard for justice from a country long seen as a global leader on accountability for victims of the gravest crimes," said Dewa Mavhinga, the NGO's Africa division senior researcher.

"It's important both for South Africa and the region that this runaway train be slowed down and South Africa's hard-won legacy of standing with victims of mass atrocities be restored," Mr Mavhinga said.

The ICC says its focus is on helping victims of conflict achieve justice

Mr Masutha said the government had also decided to drop its appeal against a ruling of South Africa's High Court, that it had violated its international obligations by failing to arrest Mr Bashir.

The appeal was due to have been heard next month.

The move to leave comes a week after the South African President Jacob Zuma visited Kenya, a country that has been highly critical of the ICC ever since the prosecutor charged its President Uhuru Kenyatta with crimes against humanity.

He denied the charges, and the trial later collapsed beceause of a lack of evidence.

The ICC and global justice:

Came into force in 2002

The Rome Statute that set it up has been ratified by 123 countries, but the US is a notable absence

It aims to prosecute and bring to justice those responsible for the worst crimes - genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes

In the court's 14-year history it has only brought charges against Africans.

Two weeks ago Burundi said it would pull out of the ICC - a decision described by the court as "a setback in the fight against impunity". MPs backed the decision and its president signed the measure into law on Tuesday.

Last year, Namibia also said it planned to withdraw from the ICC, describing the court as an an "abomination" which wanted to "dictate" to Africans on how they should be governed.

Previously, the African Union has urged member states not to co-operate with the ICC, accusing it of being racially biased against Africa by failing to prosecute suspected war criminals from other parts of the world.

The ICC denies the allegation, saying it pursues justice on behalf of Africans who are victims of atrocities.

The 124-member ICC opened in 2002. It is the first legal body with permanent international jurisdiction to prosecute genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes.

- Published25 June 2015

- Published7 February

- Published16 June 2015

- Published16 June 2015

- Published14 August 2019