Why clearing Gordhan is good news for South Africa

- Published

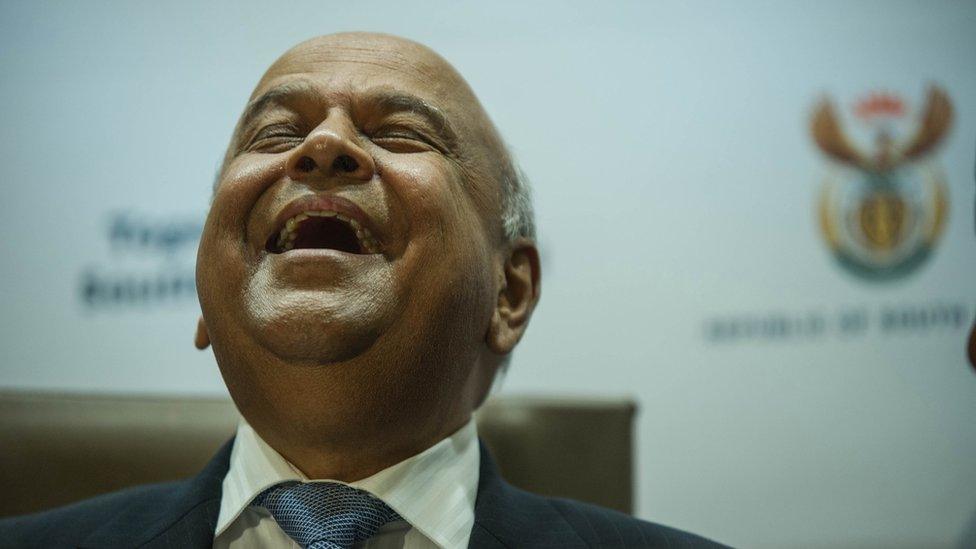

South Africa Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan has repeatedly denied any wrongdoing

The U-turn by the head of South Africa's National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), Shaun Abrahams, dropping controversial fraud charges against Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan, signals a turning point in the nation's politics.

Right from the outset, many respected individuals and civil society groups said the charges were the work of powerful individuals who wanted to loot the state coffers.

They just wanted to get Mr Gordhan out of the way because he would stand up to them.

He had been emphasising that the state should not spend money it does not have.

In what many saw as Mr Abrahams buckling under pressure, he called an impromptu media briefing following speculation that he would have no choice but to drop the fraud charges.

Why the U-turn?

In simple terms, the chief prosecutor made the move because any self-respecting judge would have thrown the case out of court, had it gone all the way to trial.

He explained that the decision to prosecute was based on advice from his fellow prosecutors who had been working on the case for months.

National Prosecuting Authority chief Shaun Abrahams (C) has denied reports that the charges against Pravin Gordhan were politically driven

He also said he found there was "no intent to act unlawfully" by any of those involved in the case.

The finance minister was charged together with two others, Ivan Pillay and Oupa Magashole, who were senior officials at the South African Revenue Services (Sars), the tax collection agency where Mr Gordhan worked a decade ago.

He was accused of costing the government more than $74,000 (£61,000) by approving an early-retirement package for Mr Pillay and then re-hiring him as a consultant.

But many saw this as a matter which could have easily been resolved without having to get prosecutors involved.

Monday's announcement contrasts with what happened just a few weeks ago, when Mr Abrahams displayed a high degree of confidence as he made the announcement that he was charging Mr Gordhan with fraud.

He said at the time: "The days of disrespecting the NPA are over. The days of not holding senior government officials to account are over."

South Africa's currency, the rand, lost 3% of its value soon after.

What does this mean for Zuma?

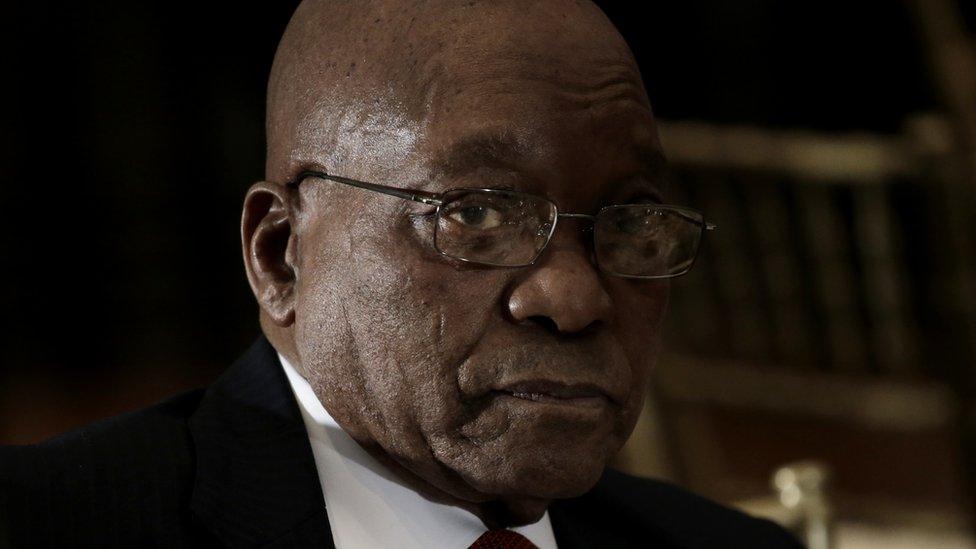

This must be humiliating for President Jacob Zuma, the man who hired Mr Abrahams.

President Jacob Zuma appointed Shaun Abrahams in June last year

When the chief prosecutor was asked on Monday whether he was embarrassed by this legal somersault, he replied: "I certainly do not owe anybody an apology. I certainly don't."

Just the day before Mr Abrahams announced the charges against the finance minister, he met President Zuma at the headquarters of the governing African National Congress.

They both denied that the charges were mentioned. Instead, they said, they were discussing the ongoing university students' protests.

But some pointed out that the minister of higher education was not present at that meeting.

It is believed that the nucleus of this debacle emanates from squabbles within the governing ANC between those who want to run a clean government and those who allegedly want to loot the state through shady government contracts.

This phenomenon is known here as "state capture" and refers to those who use undue influence on government officials and are able to manipulate them to deliver favours for kickbacks.

What about the NPA?

There is also huge concern that the NPA is being used to fight political battles.

Mr Gordhan (right) is not seen as a political ally of President Jacob Zuma (left)

More than 80 South African business leaders, 101 ANC stalwarts, civil rights groups, retired judges, opposition parties and some in the government, including the ANC's own chief whip in parliament, had come out in public to support Mr Gordhan.

They all said the charges were politically motivated.

Opposition political parties are now calling for Mr Abrahams to be debarred.

What does it mean for South Africa?

Richard Calland, author of several books on South Africa's political machinations, told me that he takes a positive view from all this.

"This shows that, although under attack from President Zuma and his cronies, South Africa's institutions are resilient," he said.

"The momentum is switching. Civil society can be heard when it raises its voice of conscience."

Twenty-two years after taking power from a white-minority government, with this controversy South Africa finds itself at a crossroads.

Many here see two possible directions.

The country could follow the same route as some other African states which crumbled under the heavy blanket of corruption and cronyism.

Or, it will rise above the cancer of nepotism and maladministration.

Many believe that Mr Gordhan is the face of those who want to show that African countries do not have to follow the route to chaos before things get better.