Libya still broken one year on

- Published

Libya is a mess. That is not news to most, but Libyan lives were supposed to have improved by now.

Saturday marks exactly a year since the signing of the political agreement brokered by the United Nations Support Mission in Libya.

The country was supposed to have one government, but it has two with a third one trying to revive itself.

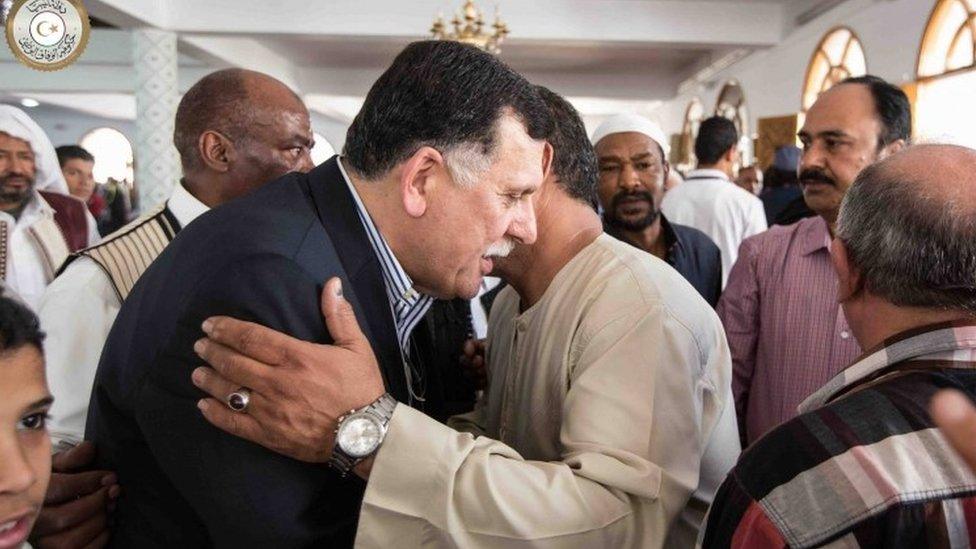

New Prime Minister Fayez Sarraj - who leads the UN-backed unity government known as the Presidency Council - was supposed to be in charge. He should not be living on a prayer that the navy base he largely operates from in Tripoli will not be raided by militias over which he has no power.

One year on, Libya's international partners, and its politicians, are still shuttling between multiple capitals in Europe and the region for talks to bridge the continuing political, economic and security impasse.

The fightback against the so-called Islamic State (IS) gained headway this month in Sirte and that battle remains paramount to the West. But with the blurred lines of leadership, can any victory on the battlefield repair the dysfunctional state of the country's affairs?

Libya will remain an attractive landscape for IS, and other strains of Islamist groups, as long as there is a power and military vacuum in the country. Its southern region is now being watched closely for both IS and al-Qaeda activity.

"Cuddly but no teeth"

The turmoil in Libya has outlived many diplomatic posts, trying to make sense of what is wrong with the country and what can be done to "fix it". Embassies of European countries and the US are still based outside Libya.

Italian and British diplomats are the only ones recently who have been spending much time in the country - during short visits, mostly confined to their respective compounds. Sources suggest that a more formal move by both missions could take place by the end of January.

Prime Minister Fayez Sarraj is seen as having little power at his command

This, however, would largely depend on the survival of the Presidency Council itself. Few believe it will endure through the coming months and most are even surprised it lasted this long.

Its own divisions still plague it, as does a shortage of funds or any guaranteed loyalty from the patchwork of armed groups the Council relies on in order to remain in the capital Tripoli.

A close confidant of one of the Council's members privately described the Libyan prime minister to me as "nice and cuddly, but has no teeth". The fact that members of his team are even discussing this should ring alarm bells.

If the Presidency Council collapses before a new or revised political and military agreement is reached, the West will be left with an even bigger mess to untangle.

Foreign powers exerted an extraordinary amount of pressure on Libyan parties to sign a political deal one year ago because they were primarily chasing resolutions to problems facing the West, not Libyans.

Their key objectives were to contain the rise of IS and stem migration into Europe.

The reality is that the deal created even more divisions within both political bodies who signed up, splitting each in two. Incredibly, it went ahead despite the absence of any viable security entity that would deliver the building blocks of a legitimate state-run army and police force.

Today, the country is living with the consequences of that agreement.

Pro-unity government fighters smile after taking back the last IS-controlled area in Sirte

Libya needed a bottom-up approach from the start, but since 2012 it was handled the other way round.

Security actors working for diplomatic missions privately admit that it is now all but impossible to disarm and reintegrate the militia fighters back into civilian roles. This leaves them in a bigger quagmire today.

Crisis Group's Claudia Grazini tells me the ongoing crisis "has deepened the country's de-facto partition into east and west" with each region "dominated by loose and fractious military coalitions".

"Amid the uncertainty around the US presidential transition, both sides risk overestimating their strength and foreign backing," she says.

The immediate priority, she adds, is to de-escalate ongoing military tensions around Libya's eastern oil crescent between rival armed groups, and to "reset" the political agreement signed last December. A broader consensus is needed.

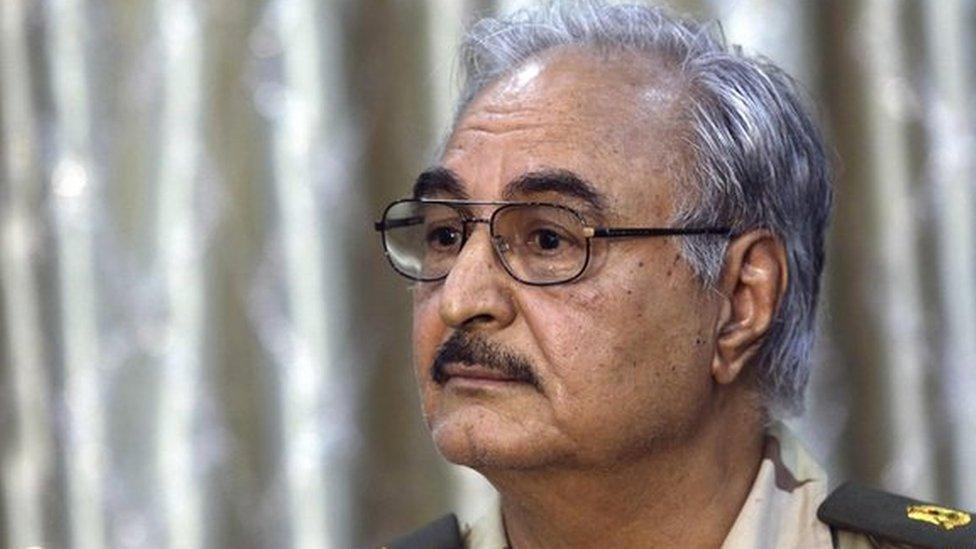

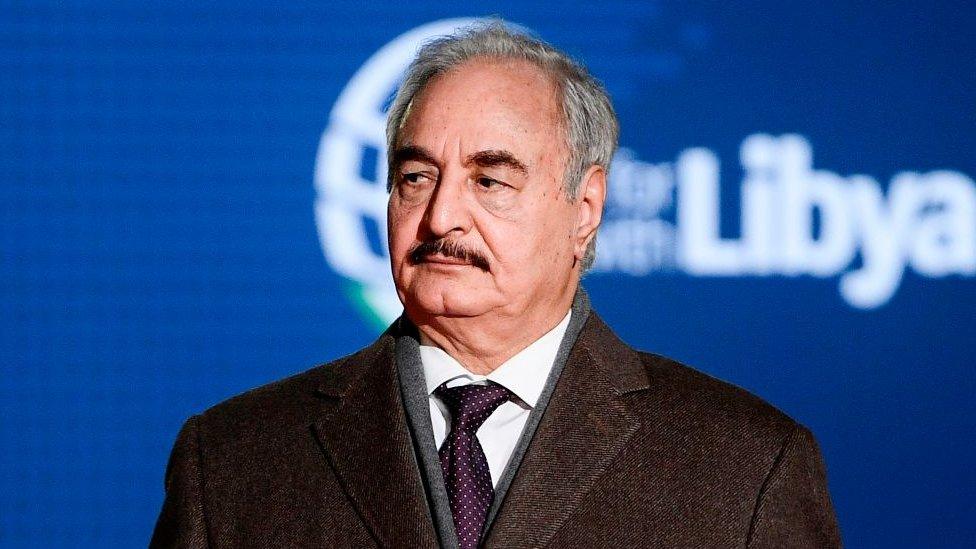

Any new deal will have to include East Libya's controversial commander Khalifa Hafter - who is increasingly playing house with Russia and appears to have ambitions for military imposed-rule. And it will need to engage the forces of West Libya, whose allegiances shift quicker than sand.

Khalifa Haftar's reappearance on the Libyan political scene has been a game changer

The military balance between the country's Eastern and Western regions' armed groups changed this summer when Hafter's forces moved into the central region to control the most important oil terminals. Since then, these ports have resumed exports for the first time in three years.

For now, Russia's interests are largely attributed to long-agreed defence and railway contracts, but it is also positioning itself to have a greater say in Libya's future. The US election results may well embolden Vladimir Putin's government to assert itself further.

There is no indication that a Trump administration will invest any game-changing effort in Libya. The president-elect has promised an "America First" foreign policy approach and, as most EU diplomats have found, Libya is not offering anything in return.

This looming reality already has many European actors worried. Although proxy wars have been playing out in the country for more than two years, some now fear that the US's detachment will serve to make Libya an open-ended playing field for an array of powers: Egypt, UAE, Qatar, Turkey and Russia, to name a few.

But given that both interventionism and the lack of it in the wider Middle East and North Africa have both been seen to have failed another view is possible: that a less engaged America might actually benefit Libyans - by giving them breathing space to come up with their own national solutions.

Libyans today are reckoning with a past, a present and a continuously evolving military scene that looks set to haunt them for many more years. The right solution is ultimately in their hands. But they need to agree on what the problem is, for others to help resolve it.

- Published6 December 2016

- Published8 April 2019

- Published23 June 2016

- Published4 April 2016

- Published13 September 2023