The UN's peacekeeping nightmare in Africa

- Published

What are UN peacekeepers doing in Africa?

One of the key issues facing Antonio Guterres, the UN's newly installed secretary-general, will be to address critical failures in African peacekeeping operations.

With this is mind, he will surely be asking himself whether the vast organisation he is now leading needs to chart a different course.

The UN spends close to $8bn (£6.5bn) every year on peacekeeping around the world, with the bulk going to missions in Africa.

A new report by the Geneva-based research group Small Arms Survey has accused the UN's mission in South Sudan (Unmiss) of lacking neutrality by giving arms to rebels in the town of Bentiu in 2013.

It blames Unmiss for underreporting arms confiscated from fleeing soldiers and handing over the weapons to soldiers of the Sudan People's Liberation Movement-in-Opposition (SPLM-IO) on more than one occasion.

The report also claims that shortly after this transfer of arms, the rebels went on to carry out a massacre of civilians.

Failure to protect

The operations of the UN's mission in South Sudan came into sharp focus after embarrassing revelations that its troops failed to protect civilians following clashes between government forces and former rebels in July 2016.

A damning internal investigation found that its peacekeeping mission in the capital, Juba had failed to achieve one of its core mandates, namely "to protect civilians under threat of physical violence […] with specific protection for women and children".

It described the troops' response as chaotic and ineffective.

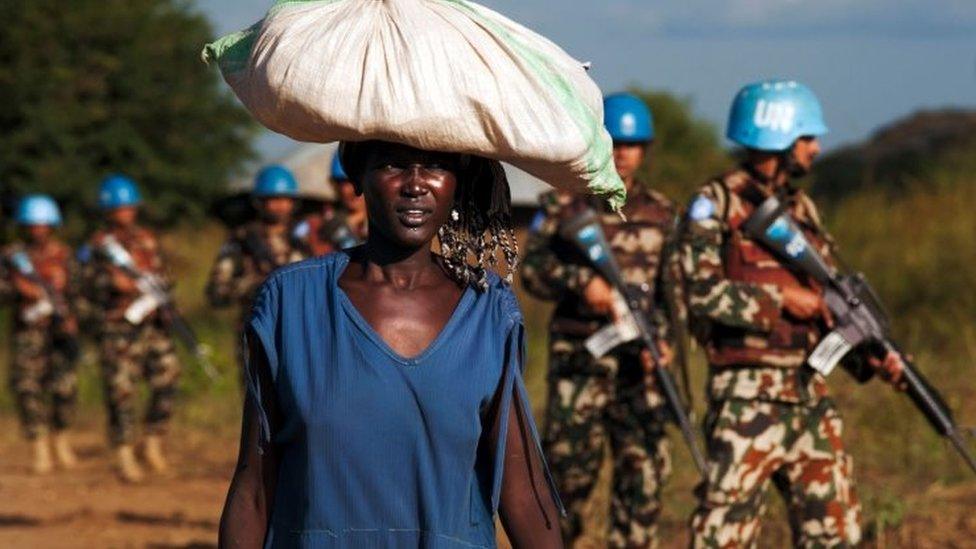

The UN has 13,000 peacekeepers deployed in South Sudan

Eyewitnesses said women and girls were raped near UN compounds with no action from peacekeepers.

Not far away, foreign aid workers suffered similar sexual violence at their residence. Their case gained much international condemnation, but it is dwarfed by the scale of the atrocities South Sudanese civilians have long experienced.

In a recent report to the Security Council, the outgoing Secretary General Ban Ki-moon offered little hope.

"There is a very real risk of mass atrocities being committed in South Sudan," he said.

"[...] The secretariat will continue to make every effort to implement the mandated task of protecting civilians through the use of 'all necessary means'.

"[But] it must be clearly understood that United Nations peacekeeping operations do not have the appropriate reach, manpower or capabilities to stop mass atrocities," his statement said.

In February, gunmen killed 30 internally displaced people and wounded more than 120 others within one of the UN's designated Protection of Civilian compounds in the north-western South Sudanese town of Malakal.

The irony of the facility failing to live up to its name was not lost on the mission's critics.

The peacekeeping mission in Ivory Coast is held up by UN figures as an example of success

The UN later accepted responsibility for its failure to prevent the bloodbath.

In the Central African Republic (CAR), the UN mission (Minusca) has also been accused of inaction when, for example, more than 75 people including civilians were killed in the north during an outbreak of violence in September 2016.

The rights group, Amnesty International, reflected on this case, saying Minusca was poorly trained and "lacks the resources it needs to adequately protect civilians."

Jean-Serge Bokassa, the Interior Minister of CAR, accused the peacekeepers of colluding with armed militias.

"What is the role of the Pakistani contingent in Kaga-Bandoro?" he asked. "Their collusion with armed groups has gone too long."

A week later, four people died in the capital Bangui during anti-UN protests.

Survivors of the attack on the UN camp in Malakal called for greater protection

In the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo, similar disdain for the UN and its peacekeeping mission Monusco (which replaced the dysfunctional Monuc), has led to violent demonstrations and attacks by civilians in the past.

Most of the anti-UN protests have taken place in the eastern region of Kivu, where armed groups continue to commit massacres, especially in the Beni region.

Peacekeepers have often been referred to as tourists because they are associated with helicopters and 4x4 vehicles.

Charles Bambara, the spokesman for Monusco, says the task of the mission is so enormous that it's easy to underestimate progress being made.

"This country was divided into three: one armed group was controlling Goma area, another one controlling Kisangani and another one controlling the capital city and the west of the country," he says.

"So the aim when this mission was established was to reunite the country. This has now been done, with the support of the DRC armed forces. We need the support of the international community.

"This is a very difficult mission. There are probably 40 or 50 armed groups present in this country, which is as big as Western Europe, so we cannot be everywhere and that's why we're targeting these groups one after the other."

One notorious and repeated blight on the UN peacekeeping scorecard has been that of the discipline - or the lack of it - of troops.

A UN inquiry has named 41 peacekeepers in relation to alleged sexual abuse and exploitation in the Central African Republic between 2014 and 2015.

Women and even minors were reportedly abused in exchange for food and clothing. The UN has taken very little action against the individual soldiers.

Protesters in Beni, DR Congo, have protested against the UN peacekeeping operation

Prosecutors in Paris said this week that charges would not be brought against six French peacekeepers following a criminal investigation into similar allegations.

Each country is responsible for charging its implicated troops but guilty verdicts might not be in a nation's best interests as that would taint its reputation in peacekeeping - although these track records are not officially considered when selecting which countries contribute to the missions.

The UN undersecretary for peacekeeping operations, Herve Ladsous, recently denied there was a crisis in UN peacekeeping.

"Some operations are working very well. For instance, we are a few months away from an end to the operations in Cote d'Ivoire and Liberia. Their success enables us to withdraw," he said.

"However, some operations are working less well, frequently because of factors linked to the local political situation and local players, rather than to the shortcomings of our operations themselves."

The take of an ex-UN insider

For effective peacekeeping, a former commander of a past UN mission, who asked not to be named, suggests:

More regional interventions, backed by the UN's logistical and financial support;

Modelling these regional interventions on the African Union's initiative for Somalia, Amisom or the South African and Tanzanian intervention in DR Congo, which resulted in more pro-active efforts.

The ex-UN insider says there needs to be more effort placed on ensuring urgency in political processes.

Otherwise, local armed groups will begin to threaten the rule of law when they discover that the UN troops only bark without biting, he says.

But analysts say the list of shortcomings of the UN operations might not necessarily mean that peacekeeping, as a concept, is a failure.

"It has to be better thought, better planned and better implemented and made more fit for purpose," says Gustavo de Carvalho, a senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS Africa).

"If you are clearer in your mandate and how you engage with the local population, it becomes a far more honest interaction between foreign and local actors."

In CAR, peacekeepers faced allegations of sexually abusing children

Mr de Carvalho proposes the following steps towards maintaining or winning back the confidence of local populations:

A transparent standard which holds UN peacekeepers and missions accountable. This would also be a way to ensure the Troop Contributing Countries (TCCs) pay more attention to the conduct of their personnel.

A system of vetting countries and troops to ensure suitability to the task and neutrality, so that TCCs are not just using UN peacekeeping to boost their foreign policy and earn their troops large bonuses.

In the end, he says, putting boots on the ground is only one way to staunch the wounds of conflict.

"Peacekeeping is a short-term tool so we need to think of how to link this to long-term peace-building process."