Are more African leaders ready to give up power?

- Published

Adama Barrow's win in The Gambia has inspired many in Africa that a ballot revolution is possible

It has been a mixed electoral year in Africa, with peaceful handovers of power, alongside allegations of rigging and incumbents refusing to accept defeat. The BBC's Dickens Olewe looks at the state of democracy in Africa.

The unexpected outcome of the election in The Gambia is by far the biggest political story of the year.

Long-serving strongman President Yahya Jammeh was defeated in an open and free election and willingly conceded to the opposition candidate Adama Barrow.

Even though Mr Jammeh subsequently rescinded his concession and has challenged the results in court, this has failed to dampen the symbolism of his defeat and the confidence it has given to many in Africa that a ballot revolution is possible.

But did this moment, widely celebrated across the continent, represent a political trend?

Two trajectories

"We have two trajectories, one in which autocratic leadership is becoming more entrenched and it is undermining independence of electoral commission and in another where there is democratic consolidation and leaders are more willing to step down like in countries like Nigeria," Nic Cheeseman, associate Professor in African Politics at Oxford University, told the BBC.

He says that African countries need to build institutions and insulate them from the influence of political leaders.

Electoral commissions also need to be well funded and protected by the law and allowed to be in charge of their own activities, like registering of voters, he says.

Key African elections in 2016:

February:

Uganda's President Yoweri Museveni won a fifth term in office in an election marred by violence and allegations of ballot fraud.

Niger's President Mahamadou Issoufou won a second term after his main opponent Hama Amadou, who is serving time in jail, pulled out of the runoff.

April:

Chad's President Idriss Deby beat his opponent Saleh Kebzabo to win a fifth term in office.

August:

Gabon's election was marred with violence and vote-rigging. President Ali Bongo won by 6,000 votes, after officially getting 95% of the vote on a turnout of 99% from his home province of Haut-Ogooue.

December:

The Gambia's President Yayha Jammeh lost to property developer Adama Barrow and conceded. He later withdrew the concession alleging that there had been voter fraud. He has since gone to the Supreme Court to challenge the results.

Ghana's President John Mahama became the first incumbent to lose an election since Ghana returned to democracy. Opposition candidate Nana Akufo-Addo also made history by winning on his third time of trying.

In Ghana, The Gambia and Nigeria last year, the electoral commissions received a lot of plaudits for overseeing free, fair and verifiable elections.

Despite the political challenges, electoral commissions have to work to earn their credibility.

Demystifying elections

Dennis Kadima, an election observer at the Electoral Institute for Southern Africa (EISA) recalls that leading up to South Africa's local elections in August the electoral commission was facing a crisis of confidence but ended up conducting a free and fair election, a situation that has reversed its public perception.

Political competition in most African countries is seen as a winner-takes-all competition.

Michela Wrong's book It's Our Turn to Eat about corruption in Kenya captures perfectly the overall guiding reason for winning power.

Ken Opalo, from Georgetown University in the US, says there needs to be a process of demystifying elections.

"African countries need to get out of the business of treating each election as a one-off event."

He adds that allowing for continuous registration of voters and staggering some elections would help manage the perceived stakes.

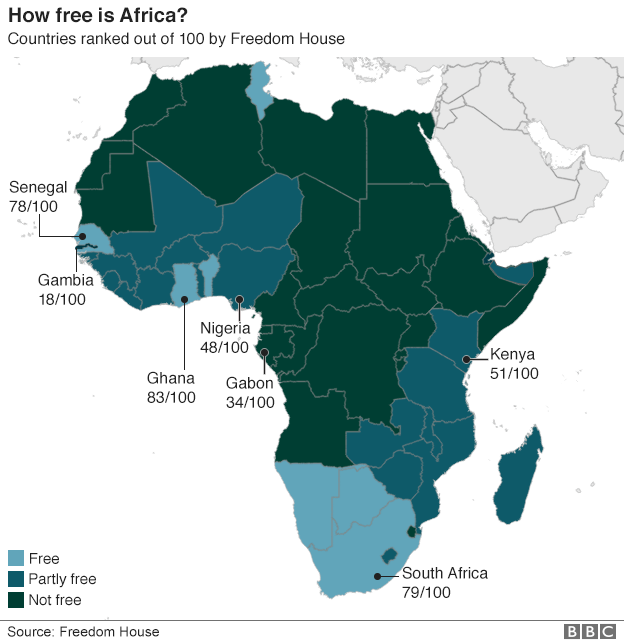

Only seven countries in Africa are listed as "free" by the 2016 report of the think-tank Freedom House.

Securing the vote

It is often in the vote-counting process that opposition parties say they have been cheated.

In Kenya, the ruling party recently defeated the opposition by passing a law allowing the use of a manual electoral system in next year's poll.

Ghana's election was widely praised, with the incumbent accepting defeat

The opposition says the push to use a manual system is a calculated plan to allow vote-rigging by manipulating the voter registration process, and providing for a less foolproof system for voter identification during voting and an easily manipulated system during transmission of votes.

This is denied by the government, which says it is a necessary back-up in case the electronic system fails.

"Part of the reason why it was so much harder to rig in Ghana is because results were announced at the local level," says Mr Opalo.

This allowed for independent verification by news organizations. Disaggregated tallying should be non-negotiable."

Mr Cheeseman, however, says posting party agents at thousands of polling stations across the country is an expensive undertaking which most political parties cannot afford.

Keep the internet on

He says that governments can easily undermine this aspect of vote watching by shutting off the internet.

Several governments including Uganda, Chad, Niger and Gabon switched off the internet during elections this year, claiming that they wanted to stop the spread of falsehoods.

Mr Cheeseman says that limiting internet access also means stopping the necessary transfer of voting information through internet-dependent applications, which makes life more difficult for election monitors.

He proposes that it might be an important step for election observers to insist on an open and free internet as a key aspect of ensuring a free and fair election.

Mr Kadima says that EISA has a benchmark of what constitutes a free and fair election: "We look at voter registration and work with political parties, civil societies and judiciaries" to ensure that standards are met.

'Pride in good elections'

Kamissa Camara, West and Central Africa officer at the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), says that beyond the use of foolproof electoral systems, positive influences could also be playing a part in helping countries in West Africa hold credible elections.

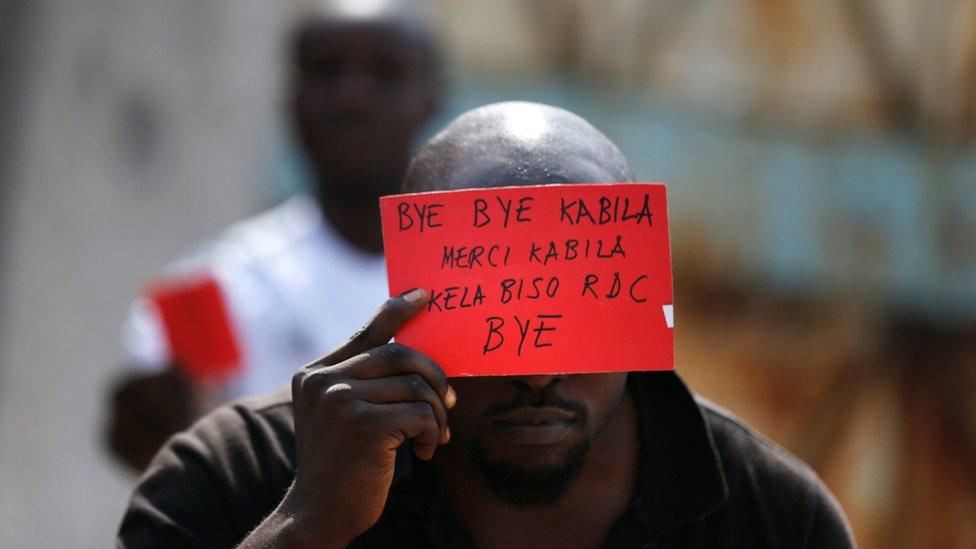

The mandate of DR Congo President Joseph Kabila expired in December but he has been unable to organise elections to find a replacement

"We have seen several peaceful elections in Benin, Senegal, Burkina Faso and in Mali and you see people taking pride in holding good elections and that desire to hold a good election is spreading."

"Democracy is making headway in West Africa thanks to shared positive expertise," she adds.

Mr Kadima says that in assessing the state of democracy in Africa, it is important not to forget that there are 54 disparate countries on the continent and it would be unfair to compare them.

"All these countries have different histories. Some are evolving while others are in a cycle but one thing is for certain, as we are seeing in DR Congo, the resilience and aspiration of the people for change will never die."

As for what to expect next year, Mr Opalo says the Kenya election is the one to watch.

He projects that there will be some violence but adds that it would be a reflection of what is at stake, rather than a descent into complete chaos and state failure.

He also says it would be interesting to follow developments in Rwanda, where President Paul Kagame is expected to run for a third term.

Read more:

- Published10 December 2016

- Published19 December 2016