How Gambia's Yahya Jammeh lost his grip on power

- Published

Gambia's Yahya Jammeh surprised the world on 2 December by accepting that he had lost elections to the relatively unknown Adama Barrow - though he now says he will contest the result. The BBC's Umaru Fofana looks at the reasons why the strongman lost his 22-year grip on power.

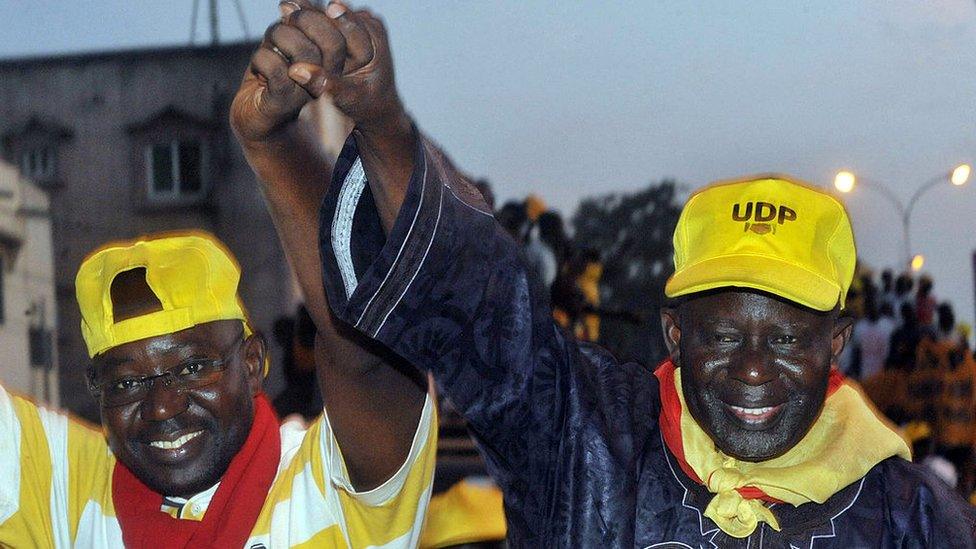

The Darboe effect

Perhaps Mr Jammeh's biggest mistake was the detention of the main opposition leader, Usainou Darboe, of the United Democratic Party (UDP).

For many years, Mr Darboe had been an albatross round Mr Jammeh's neck - the biggest challenge to his presidency.

Under Mr Darboe, the opposition tried and failed many times to have a united front. As leader of the biggest opposition party, he always wanted to be the presidential candidate.

Adama Barrow was helped by the many mistakes of Yahya Jammeh

He and Halifa Sallah, another consistently critical voice of Jammeh now touted as the next vice-president, were always in disagreement about who should head a possible coalition of their two parties.

With Mr Darboe out of the scene and in a prison cell, the UDP and Mr Sallah's party - as well as other parties - found it easy to hammer out a deal for a united front.

The result was the unexpected candidacy of Mr Barrow.

Mr Darboe has since been freed on bail.

Mr Darboe caused Yahya Jammeh more political harm as a prisoner than a free man

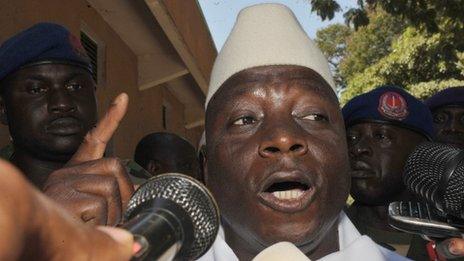

Ethnic alienation

In addition to accidentally pushing the opposition into a united front against him, Mr Jammeh managed to alienate the Mandinkas, the largest ethnic group in The Gambia.

The Mandinkas were very bitter at what they deemed as derogatory remarks made by the president, who comes from a minority group. This galvanised them to vote for the opposition.

I heard anti-Jammeh remarks from Mandinkas across the country, all citing statements he reportedly made, indicating that they would never rule the country.

Youths demand freedom and jobs

Perhaps Mr Jammeh could have been shrewd enough to avoid pushing his opposition into an unbeatable coalition or to avoid galvanising the Mandinkas into a hostile electoral force.

But after 22 years in power, he could do nothing in the face of another factor behind his defeat: The unquenchable desire for change among young Gambians, like Fatoumata Bojang, who have known no other leader.

The high rate of unemployment turned Gambia's youth against Mr Jammeh

The median age of Gambia's population is 19.9 years. They cite a lack of jobs, saying this is why so many Gambians have tried to make the perilous journey to Europe by boat.

At opposition rallies, it was mostly young people.

At a rally in Brikama, Momodou Ceesay demanded "freedom" saying he and his peers had never fully "enjoyed our rights".

That resonated everywhere I went. Students I met at the University of Gambia said the same thing.

Such is the generational divide that two families I met were sharply divided.

A woman who wanted to be known only as Njai said her parents were supporting Mr Jammeh, while she and her other siblings were voting for Mr Barrow.

She cited freedom and jobs, or the lack of both, as the main factors.

The economy worsened matters. Senegal's economic blockade earlier this year effectively killed a dying man.

Virtually all The Gambia's imports come through Senegal.

The blockade was severely felt and drew rage from the citizenry.

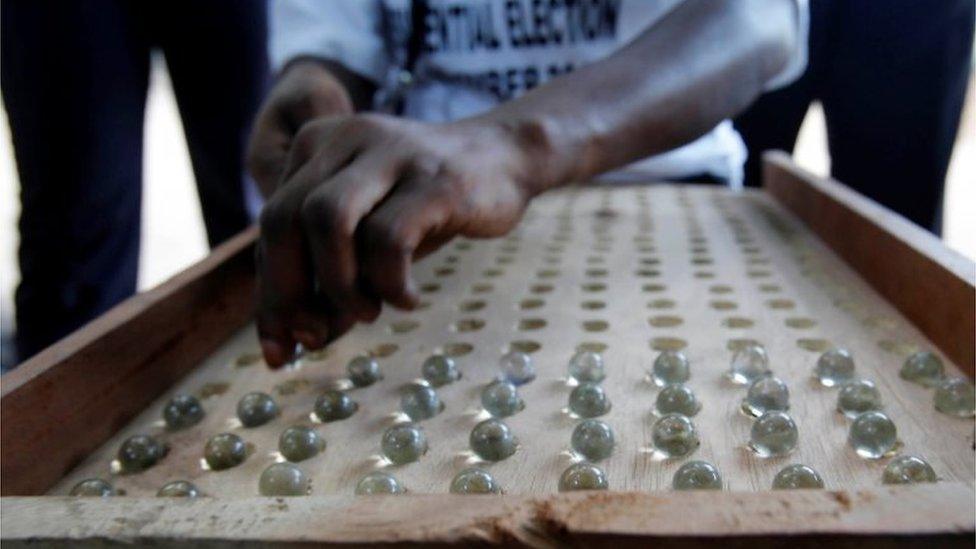

Counting the votes

There were allegations of cheating at the 2011 polls which President Jammeh won, although I was there at the time and did not see any sign of that and he denied it.

This time, such was his confidence that he agreed to calls for an electoral system to allow on-the-spot counting of votes.

Votes were counted at each and every polling station and figures published instantly.

The marble voting system was praised by Mr Jammeh as "rig-proof"

Tallying was also done at nearby centres, in the open. And counting the marbles in a specially-designed tray was very quick.

This reduced the possibility of cheating.

Gambia's electoral commission has received less praise than it deserves, I think.

It is rare in Africa for an opposition challenger to heap as much praise on the head of the electoral commission as did Mr Barrow before the polls.

He told the BBC in the run-up to voting day that the chairman of the Independent Electoral Commission Alieu Momarr Njai was trustworthy and honest.

The quiet self-effacing 82-year-old says the system does not allow for rigging.

"It will easily be noticed," he told me.

Women power

The role of women was huge. In the early queues at Sukuta, Banjul and Serekunda, there were more women than men, many of them young.

All sides encouraged Gambia's women to turn out and vote

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) invested a lot in them.

Its programme specialist Bashirou Jahumpa says in addition to building the capacity of the electoral commission through training for their staff, it also funded the National Council on its civic awareness programme and voter education.

It also helped mobilise women to vote.

Gender activist Fatoumata Jallow was also a huge pillar in this regard, campaigning for women to vote.

But it is also true that Mr Jammeh's government put women impositions of trust and engaged them to be politically active.

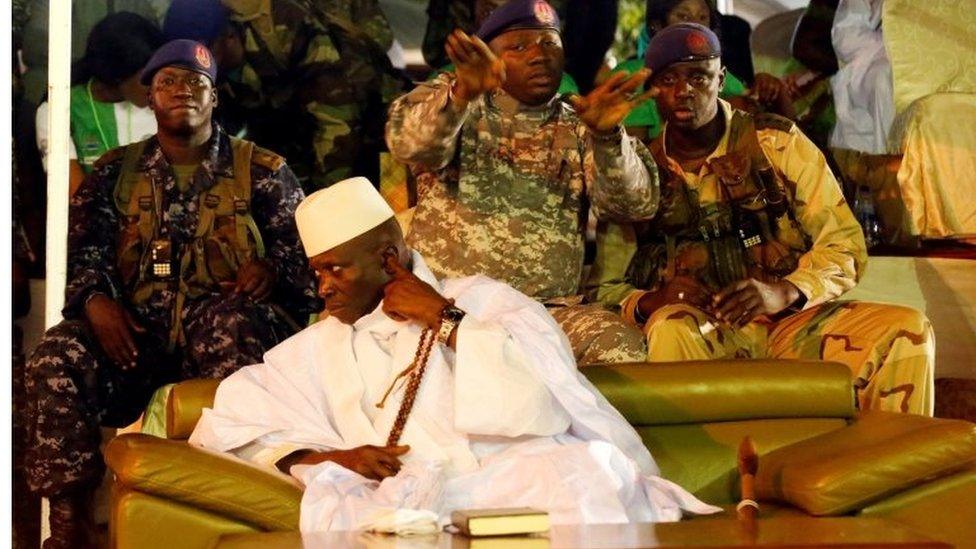

The last straw - the army

Perhaps, Mr Jammeh could have found a way to win despite all the adverse factors if he had the support of the army.

He came to power through the army. He stayed in power through the army. He relied on the army for everything.

The Gambia's army let down the man they carried to power 22 year ago

Even though soldiers were seen clad in Jammeh T-shirts and transporting party paraphernalia during campaigning, they shook hands with civilians during celebrations marking his defeat.

Intelligence and diplomatic sources say he tried to compromise the results but the top echelons of the army warned him against it.

That would prove to be the straw that broke the camel's back.

A Jammeh-inspired coup or other military interference could have denied Mr Barrow the presidency.

But instead, the army stood by and let the democratic process carry on, as it is supposed to do.

- Published2 December 2016

- Published2 December 2016

- Published22 January 2017

- Published12 April 2023