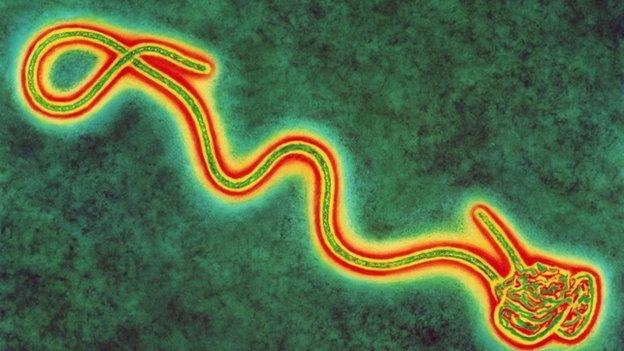

Where are Sierra Leone's missing Ebola millions?

- Published

Alhassan Kemokai questions why essential supplies did not reach Kenema hospital

Nearly three years after Ebola hit Sierra Leone, millions of dollars in funds raised to fight the deadly virus have still not been accounted for.

Alhassan Kemokai was infected with Ebola in September 2014 by his mother, who later died of the virus. She had been working in the radiology department at Kenema Government Hospital, on the frontline in the fight against the outbreak which had hit Sierra Leone four months earlier.

"My mother's death is attributable to the fact that she lacked such basic things as gloves, which was how she got infected as she helped an unsuspecting Ebola patient," Mr Kemokai says.

The outbreak, which started in Guinea in December 2013, engulfed Sierra Leone, killing nearly 4,000 people. The dead included more than 200 health workers, of whom more than 50 worked at the Kenema hospital.

In the sleepy suburb of Heigbema (whose name translates as "going elephant-watching"), Mr Kemokai struggles to look after his family. In the early evening, his two biological and four adopted children sit expectantly, waiting for the day's meal.

As smoke billows from the kitchen behind him, Mr Kemokai rubs his eyes. He recalls his then 63-year-old mother, a clerk radiologist who he says was "the elephant in the family carrying all the load". He says all of that is now on his shoulders, with no sustainable income.

Did corruption lead to more Ebola deaths?

Mr Kemokai got infected at a time when huge funds had been released to fight the epidemic. The money came from the national coffers and private donations made to the state. However, supplies needed to respond to the outbreak were still in short supply.

An internal audit of the first six months of the outbreak said at least $14m (£11m) had been misappropriated or was unaccounted for.

The audit also said that no proof existed that payments of high-risk health workers' hazard allowances, amounting to more than $4m, had been paid. During the outbreak it was commonplace for payment of such allowances to be delayed.

Gloves were not available for all Sierra Leonean health workers coming into contact with Ebola patients

This led to dramatic strike action in late 2014 at the Kenema hospital. Members of the specialist burial teams brought out corpses from the morgue and placed them at the hospital entry points, demanding unpaid allowances.

Andrew Bockarie, a hygienist, joined the strike. But his action was over more than just a payment delay.

"I was signing for 2 million leone [$360] a month" he said, "but I only received 1.5 million Leone."

Mr Bockarie said this went on for eight months, meaning he was owed 4 million leone. He says this was "stolen" from him by those administering the Ebola funds.

Nothing was done about the misprocurement, says auditor general Lara Taylor-Pearce

Two years since a damning report on the handling of funds to fight the Ebola outbreak, Sierra Leone's auditor general, Lara Taylor-Pearce, says some of the missing money remains unaccounted for.

And not much has been done to bring those responsible to book.

"We're expecting a situation where monies are to be refunded, withholding taxes are to be repaid. Ambulances that had to be supplied - we're not aware that they've been supplied," she says.

Ms Taylor-Pearce says there was no proper accounting for how the funds were spent, and procurement procedures for ambulances were not properly followed, with many of the vehicles not supplied.

She told the BBC that the extent of the misappropriation adversely affected the response to the disease and could have cost lives.

Following publication of her report, a dispute arose between parliament and the anti-corruption commission over which body should act on it. In the end, the parliament won, citing constitutional provisions.

This new cemetery was established for Sierra Leone's nearly 4,000 Ebola victims

But many have criticised its handling of the matter. Only a handful of civil servants have been suspended as a result of the investigations.

"There was a bit of a problem in the implementation of our recommendations," says Ms Taylor-Pearce. "We were looking for a situation wherein these monies [would be] refunded, for situations wherein items that were not delivered like ambulances… could have been delivered.

"I am not aware that anything was done about the misprocurement," she says.

Presidential spokesman Abdulai Bayraytay says the revenue authority "has gone into some arrangements with some people [and] they started paying in piecemeal".

He says that "when such monies are being paid, it shouldn't be done in secret. They should go public - that way the payment in itself, the naming and shaming, will even serve as a deterrent."

Mr Bayraytay said the presidency was "alarmed" by the auditor's report and was confident that those named would eventually be held accountable.

Health charity MSF was part of the international response to Ebola in Sierra Leone

A local campaign group, the Centre for Accountability and Rule of Law (CARL), says it remains dissatisfied.

While lauding the efforts of the audit service, CARL's Joseph Lamin Kamara says: "Sadly the relevant state institutions have done little to ensure accountability for the missing funds."

He says the report's allegations should be fully investigated and wrongdoers brought to justice.

Three years on, there is still no confirmed total of the number who died from Ebola in Sierra Leone. But there is little doubt that lives could have been saved if millions of dollars hadn't been mismanaged or stolen.

Nothing can soothe the grief of the bereaved. And it remains unclear if those responsible will ever be held to account.

Mr Kemokai and his six dependants are just a few of those living with the consequences of Ebola and a mismanaged government response.

- Published13 November 2014

- Published7 November 2015

- Published23 March 2015

- Published8 October 2014