What happens when aid is given as direct cash transfers?

- Published

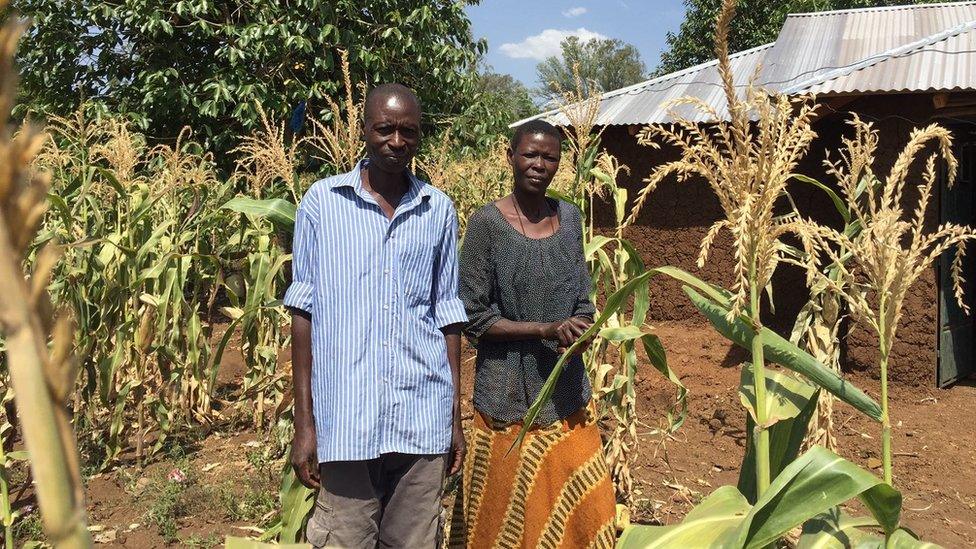

Joseph Ombimbo Nyakwaka and his wife Beatrice used their cash transfer to buy seeds and improve their home

What is the best way of ensuring aid money is used effectively and efficiently? In Kenya, charities are experimenting with direct cash transfers, allowing individual recipients to spend the money on whatever they like.

Thousands of groups spend billions of dollars every year helping tens of millions of people.

Whether it's a response to a humanitarian crisis or trying to lift communities out of poverty, aid accounts for a hefty chunk of the budgets of governments, UN agencies and international organisations.

It takes many different forms: sacks of grain delivered to hungry people, tents provided to the homeless or displaced, and increasingly it's cash - delivered electronically to a phone or credit card.

Some cash comes with conditions - allowing the bearer to buy only certain things for example, but there's a surge of support for unconditional direct cash transfers, because the research shows it can be incredibly effective.

What happens when aid is given in cash? How would you spend $1,000?

"Cash transfers are one of the social programmes that have been most extensively studied and we know that they can be very effective," said Francesca Bastagli from the Overseas Development Institute, which published a detailed report on the subject.

"Cash transfers increase people's income, people's consumption, particularly food consumption, but also improve dietary diversity.

"We find strong evidence linking cash transfers to increasing school attendance, health care visits, household savings, and increasing investments in productive assets."

In Kisumu, western Kenya, a charity called GiveDirectly has spent more than five years giving out large lump sums of money.

With the strapline "We aim to reshape international giving", it was started by a group of Harvard and MIT economics students and its impact has been closely researched.

Each recipient is sent about $1,000 (£800) in two or three instalments and they can spend the money on whatever they like.

"We find strong evidence linking cash transfers to increasing school attendance, health care visits, in household savings, and increasing investments in productive assets."

Francesca Bastagli, Overseas Development Institute

A new roof was a popular purchase in Kakojo village two years ago when the cash popped up on the phones of those selected.

"We use a variety of different indicators like asset ownership, the size of the house, the number of kids, that kind of thing," said Will Lee, the charity's country director for Kenya.

Emily Aeino Otieno's new tin roof not only helps her collect runoff water when it rains, but it saves her the money she was using to repair thatch twice a year.

"I'm happy because I'm not using any more money on my roof," she said.

"I can use that money to buy my clothes, food, pay school fees and other expenses."

And she also has a little business buying cooking fat in bulk and selling it off in small packets.

Joseph Ombimbo Nyakwaka and his wife Beatrice bought some seed and fertiliser and were harvesting maize to eat and sell.

They also paid for two cows and two calves as an investment, some wooden beams to improve their home, school fees for one of the children and even had some left over to pay a dowry - more than 30 years after they were married.

GiveDirectly claims 91% of the money people donate goes directly to those in need - taking out many of the overheads.

Water search

And it's not just charities or non-governmental organisations which are increasingly turning to the direct payment route.

The UK government's Department for International Development (DfID) funds them elsewhere in Kenya - in the drought-hit counties in the arid north and north-east.

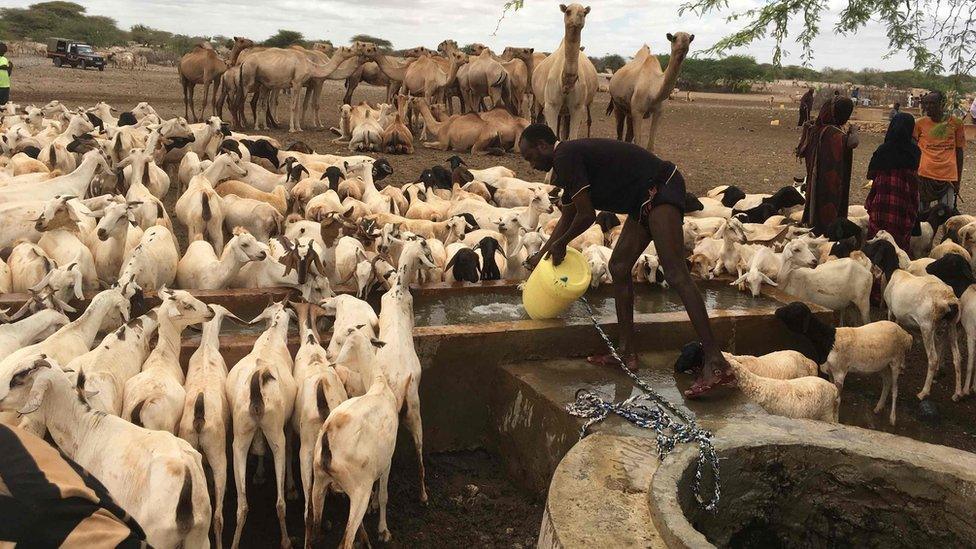

In Wajir County, the cattle graze on whatever scraps of grass they can find as they plod through sand under a burning sun.

The pastoralists here are mainly nomads, leading their cattle, sheep, goats and camels to the water holes, but struggling to find them pasture.

Abdullahi Haji Abdi used to have 100 head of cattle, but the last big drought took many of them, and now he's trying to hold on to the few he has left.

The UK's Department for International Development has experimented with cash transfers in some parts of Kenya affected by severe drought

When times are tough the animals are sold to pay the bills - often when the price is at its lowest - and when the rains return the assets are gone and people just get poorer.

"If it wasn't for these cash payments I'd have to sell the livestock to pay for school fees, food for the family and the basic things," he told me.

When the credit is remotely added to his plastic card he pops it into one of those machines that normally takes debit card payments, and the teller checks his identity by scanning his fingerprint.

She then hands over the $25 or so he receives each month from a black plastic bag full of cash.

It's called the Hunger Safety Net Programme and provides regular payments to more than half a million people - 34% of that money was provided by Kenya last year, the rest funded by DfID.

The Kenyan government's National Drought Management Authority also makes payments to hundreds of thousands more people when drought starts to bite - all that money is provided by UK taxpayers.

In the UK, there has been criticism of government aid payments - especially in relation to direct cash transfers - with suggestions people would waste it or abuse the system.

"There is no evidence that recipients of cash transfers are using this cash on goods such as alcohol or tobacco," said Ms Bastagli from the Overseas Development Institute.

"There's a common claim that cash transfers can make people lazy or make them work less, but there's no evidence to suggest cash transfers lead to a reduction in people working."

- Published26 February 2017

- Published16 February 2017

- Published13 February 2017